Before global outlets paid attention, this small site had been digging into Adani Group for years despite lawsuits and threats

Activists from India's Congress Party hold placards and shout slogans, demanding a probe into the Adani Group in Mumbai. REUTERS/Francis Mascarenhas

The Adani Group, a multinational conglomerate founded by Indian billionaire Gautam Adani, has received extensive coverage from global news organisations in the last few weeks.

On 24 January Hindenburg Research, a US-based investment research firm, published a report arguing the Adani Group was pulling off the “largest con in corporate history”. According to the report, the Adani Group was involved in stock manipulation, accounting fraud and money laundering. As a result, Adani’s stock prices plummeted resulting in losses of more than $100 billion and the group had to cancel a further share sale.

The market’s turmoil didn’t come as a surprise for small news site Adani Watch, whose contributors had already published investigations on the group’s offshore investments in July 2021.

“Thanks to Hindenburg, the world finance system is taking a dim view of the group’s set-up and the web of offshore tax-haven entities brought to light by our site,” says editor Geoff Law, highlighting the work of Delhi-based journalist Ravi Nair, who wrote this two-part series on Adani group’s offshore investments back in July 2021.

According to its own website, Adani Watch is “a non-profit project established by the Bob Brown Foundation to shine a light on the Adani Group’s misdeeds across the planet.” Bob Brown, a former Senator from Australia, set up the foundation to promote environmental awareness.

Activists, including Brown, heard about the Adani Group when it announced it would dig the biggest coal mine in Australia’s history – the Carmichael coal mine in Queensland. Adani Watch began to create awareness about Adani’s involvement in the mine in October 2019. The website is solely funded by the foundation.

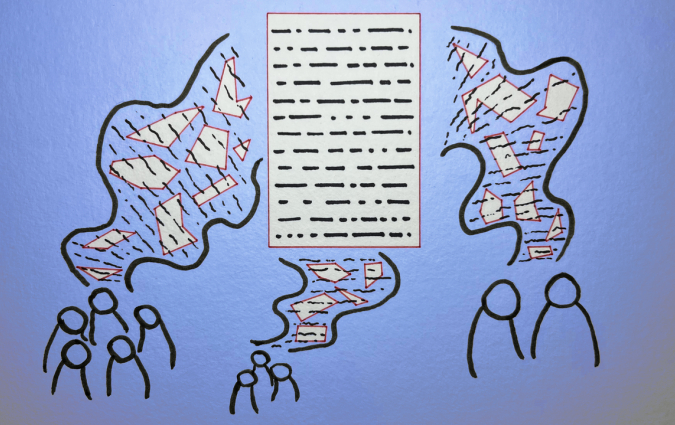

The mandate of Adani Watch quickly expanded to the conglomerate’s activities beyond the Carmichael mine. The website developed a network of contributors to explain and document Adani Group’s activities and its impact on the environment and human rights in India, Myanmar and Indonesia. At any point, they had a dozen contributors.

Gautam Adani, the Chairman of the Adani Group is seen as a close aide to Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Independent observers suggest this is the reason why the Adani Group has bagged massive government contracts in energy and big infrastructure development in the last few years.

Today the Adani Group has an overarching presence in the Indian economy. The group is building around 18 highways, making it one of the biggest road constructors in India. It also controls one-fourth of India’s air-passenger traffic and one-third of its air-cargo traffic. The group mines coal, generates and distributes electricity in India and beyond. Most recently, they entered the solar market and bought a large TV network with a reputation of being critical of the Modi government.

All these investments have raised questions about whether the Adani Group is too big to fail. “They are so big that we have no choice as journalists but to keep tabs on them,” said Ravi Nair, the journalist who published the series on the Adani Group’s offshore investments for Adani Watch.

Intimidation of journalists

Gautam Adani’s personal wealth has increased exponentially in Narendra Modi’s second term. According to Bloomberg Billionaires Index, Adani’s wealth grew 13 times from January 2020 to August 2022. While he got richer, criticism and questioning of the powerful in India has become increasingly tough: the country has fallen eight places from 142 to 150 out of 180 in the 2022 World Press Freedom Index.

Reporting on the Adani Group has been an uphill task for Indian journalists. Some reporters who dared to investigate the company came into legal troubles. In July 2022, Delhi police landed up on Nair’s doorstep with an arrest warrant. The Adani Group had filed a criminal defamation case against him about 1,000 kilometres away in Gandhinagar, the capital of Adani’s home state of Gujarat.

Nair was accused of defaming the conglomerate in 26 tweets. Each tweet linked to a story on the Adani Group, several of which Nair had not written. “They filed a case against me for tweeting links to stories someone else published,” he says.

Something similar happened in January 2021, when journalist Paranjoy Guha Thakurta was served an arrest warrant for two stories on the group’s closeness to the Modi government and on its possible tax evasion that were published in The Wire and in the Economic and Political Weekly.

First the Adani Group sent legal notices to the publications, asking them to take down the articles. When the EPW took them down, Thakurta resigned as its editor.

In 2020, the conglomerate asked a lower court in Gujarat to keep Newsclick, a news website, from reporting on one of its companies, Adani Power. The court duly issued gag orders.

According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, the conglomerate has filed defamation suits against journalists including Bodhisatva Ganguli, Pavan Burugula, and Nehal Chaliawala of the Economic Times; Latha Venkatesh and Nimesh Shah of CNBC TV18; freelance journalist Paranjoy Guha Thakurta; news website Newsclick; and the news magazine Economic and Policy Weekly.

These lawsuits are instruments to intimidate journalists and rarely result in a conviction. “They did not question the stories that I tweeted. They only questioned a Twitter thread that gained traction,” says. Nair, who is out on bail but continues to fight the case. The mounting legal costs on journalists, the time-consuming paperwork and the visits to remote areas where the courts summon make life difficult for reporters like Nair and act as a deterrent for any others who may be thinking of following his lead.

“These examples make it essential to have scrutiny outside the country,” says Geoff Law, the editor of Adani Watch.

This is a view shared by Geeta Seshu, a member of the Free Speech Collective, a website that monitors free speech in India. She thinks these cases push other journalists to self-censor or drop investigative stories altogether. “In effect, very few journalists will then dare to report on big wigs like Adani,” she says.

Thakurta has had similar criminal defamation suits filed against him by large corporations such as the Reliance Group and the Sahara Group. “The difference is they never took me to court,” says Thakurta, who makes many visits to the courts in the six defamation cases he is battling, slapped on him by the Adani Group.

Business journalism in crisis

Adani Watch is a unique news organisation. Its only goal is keeping tabs on an Indian conglomerate from outside the country. There are three reasons for this.

The first one is the crisis in business journalism. “Business journalism in India is not investigative. It is mostly reliant on information leaks,” says Seshu from the Free Speech Collective. Moreover, since news organisations are so reliant on advertising, they do not want to antagonise companies that advertise on their sites. News articles often become PR pieces for certain companies. Hard hitting questions in public interest are rarely raised.

The second reason is that most Indian news outlets do not allocate enough money for investigative work. In addition, there is a chilling effect caused by several legal cases. “As a journalist, I would prefer to publish my stories in Indian publications so they gain maximum traction, but who will publish them?” asks Nair.

The third reason why Adani Watch’s work matters is more practical: although India is facing a democratic backsliding, there are still avenues to unearth information. “We would not have been able to run a website that would keep tabs on a Chinese conglomerate or Russian oligarchs,” says Law.

When Adani Watch began in 2019, Law received many pitches for stories from India, but as time passed journalists have become more reluctant to put their byline on them. “Despite this,” he says, “there is still some rule of law in India and it’s possible for journalists to do stories from inside the country.”

Law, who joined the environmental movement in Australia in the early 1980s, compares the work of his publication with David’s fight against Goliath. However, he says, he and his colleagues are used to battling big corporations. He was a part of the 2004 $6.5m lawsuit by Australian timber company Gunns against environmentalists who opposed its logging operations.

Nine years after filing it, Gunns was forced into liquidation. Law says that the aim of Adani Watch is a bit different. “We are only focused on uncovering the misdeeds of Adani Group, and not aiming for any specific outcome,” he says.

However, he said, if he were to name one thing he wants to see change as a result of his work at Adani Watch, it's this: “I would want the Indian government and the Adani Group to realise the importance of Hasdeo forest,” referring to the largest contiguous dense forest in central India where Adani Mining is fighting to expand a coal mine. “I would urge them to withdraw from the area and protect the Adivasis (indigenous peoples),” he says.

Raksha Kumar is a freelance journalist, with a specific focus on human rights. Since 2011, she has reported from 12 countries across the world for outlets such as 'The New York Times', BBC, the 'Guardian', 'TIME', 'South China Morning Post' and 'The Hindu'. Samples of her work can be found here.

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time