In this piece

Hydroxychloroquine in Australia: a cautionary tale for journalists and scientists

Mask-wearing women hold stretchers near ambulances during the Spanish flu pandemic

in St. Louis, Missouri, U.S. in October 1918. Photo: Library of Congress handout

In this piece

We learn from history that we do not learn from history | Scientific misinformation in the COVID-19 pandemic | A secret overseas mission | One of the biggest retractions in modern history | The four horsemen of irreproducibility | The story could have ended there | Look for “the tipping point” | The epilogueIn October 1918, the devastating second wave of the influenza pandemic was reaching its peak. Close to 200,000 Americans would die in that month alone. The virus was killing young and healthy people, sometimes within hours of onset. The first infected ship had just arrived in Australian waters.

As Australians braced for the virus’ impact, newspapers were flooded with claims of surefire remedies, many of which have been documented by historian Philippa Martyr. “Cures? My goodness me, the vast amount of cures on the market are positively frightening, and everyone has a favourite cure,” wrote a journalist in the Bendigo Independent on 19 October 1918.

“Our chemists are driving a brisk trade in patent influenza cures,” another paper reported in Orange, New South Wales.

One popular remedy - despite a lack of evidence it worked - was the antimalarial drug quinine. It was promoted in newspaper ads from Britain to the United States. More than 100 years later, a descendant of quinine would play its own role in the desperate search for a treatment against a new, lethal and poorly understood virus: COVID-19.

We learn from history that we do not learn from history

On 7 January 2020, The Australian newspaper carried the country’s first reports of “an unidentified illness in the central Chinese city of Wuhan”. By the time a global pandemic was declared on 11 March 2020, the virus had taken more than 4,000 people’s lives and been detected in more than 100 countries.

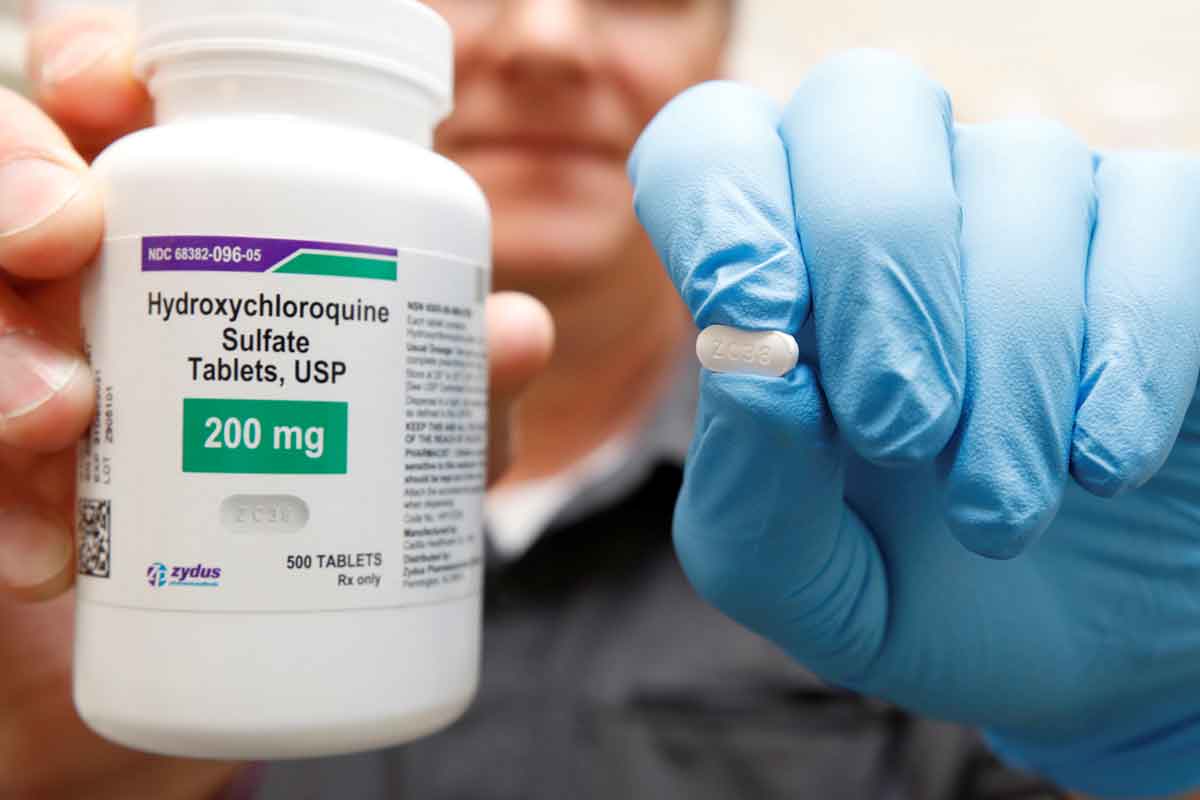

In those early months, without any vaccines on the horizon, any cheap and effective treatment was the best hope of averting a global catastrophe. There was good reason to look at drugs that had been in use before, whose side effects were known and whose patents had long expired. Hydroxychloroquine – an advanced, synthetic form of quinine used for decades in the treatment of malaria and autoimmune conditions – was an obvious candidate.

As with quinine 100 years earlier, hydroxychloroquine’s potential received wide acclaim in early media reports. It was championed by some doctors and scientists and it led to drug shortages in Australia and beyond. However, despite the initial high hopes of the scientific community, it would ultimately prove to be of little benefit.

The drug also became a cause célèbre in the anti-vaccine protest movements for whom the pandemic represented more sinister forces at work. Central to their worldview was “a deep distrust of science [and] a strong belief in conspiracies,” political sociologist Josh Roose observed. Seen through this lens, hydroxychloroquine was a cheap and effective “cure” being deliberately withheld to protect the vaccine profits of pharmaceutical companies or score points against political opponents.

The story of hydroxychloroquine shows the difficulties of reporting on a flood of new and often contradictory scientific studies; the need for sober treatment of claims about “breakthroughs” and “cures”; the potential for fraud, sloppiness and overhype within science itself; the tendency of partisans to interpret science in ways that defend their ideology; the role of public figures in promoting false and misleading information; the acceleration of that misinformation on social media; and the dangers when science is politicised and becomes embroiled in conspiratorial culture wars.

It reminds us that the spread of misinformation is not always the work of nefarious actors; that it can inadvertently be reproduced by journalists and editors working in good faith to report science at great speed and under immense pressure, and that this work can have consequences on the decisions people make to protect their health.

Scientific misinformation in the COVID-19 pandemic

The warnings were there early. In March 2020, the co-founders of Retraction Watch, Adam Marcus and Ivan Oransky, wrote in Wired magazine: “Much of the blitzkrieg of science that emerges in the coming days and weeks will turn out to be wrong, at least in part, and that’s not a bad thing.” Without clear communication of uncertainty, the situation was ripe for exploitation by populist politicians and keyboard warriors.

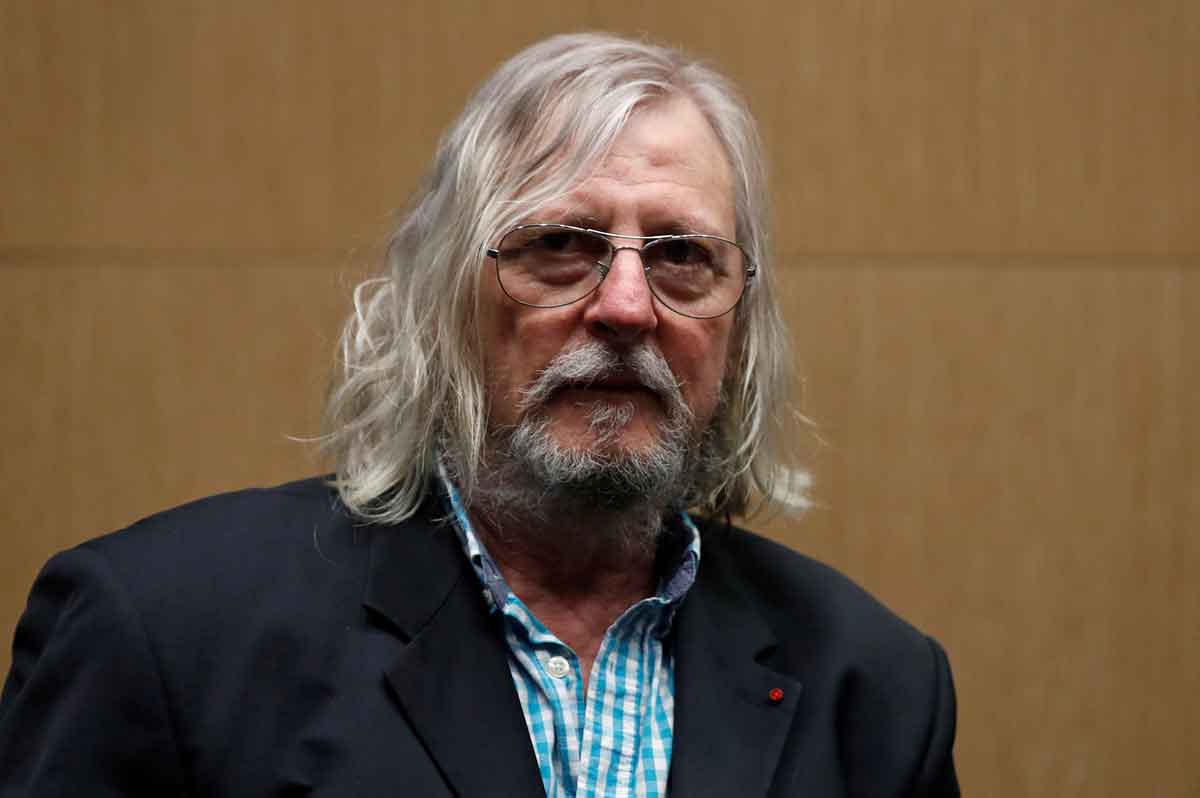

In February 2020, early in-vitro and small human trials in China had shown promising results for chloroquine and its derivative, hydroxychloroquine, against COVID-19. French microbiologist Didier Raoult, a respected infectious diseases specialist with a reputation as a contrarian, was greatly enthused by these studies.

In late February he appeared in a YouTube video titled Coronavirus: Game Over!, declaring: “This is probably the easiest respiratory infection to treat of all. The only thing I’ll tell you is, be careful: soon the pharmacies won’t have any chloroquine left.”

Raoult’s research hospital soon launched its own clinical trial. So promising were its initial findings that Raoult halted the trial after just six days so the outcomes could be shared. The study, published in the International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents on 20 March, reported that all six patients treated with hydroxychloroquine and the antibiotic azithromycin were “virologically cured”.

Despite the limitations of the study, notably its small size, the findings hit the mainstream media in a blaze of publicity. Raoult authorised New York lawyer Gregory Rigano to promote the study’s findings before they were published. “We have a strong reason to believe that a preventative dose of hydroxychloroquine is going to prevent the virus from attaching to the body, and just get rid of it completely,” Rigano told Fox News host Laura Ingraham on 16 March.

Two days later, Ragano appeared on Fox News again. “What we're here to announce is the second cure to a virus of all time,” he told host Tucker Carlson, describing the paper as “a well-controlled, peer-reviewed study that showed a 100% cure rate against coronavirus.” A few days later, President Donald Trump tweeted that hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin “have a real chance to be one of the biggest game changers in the history of medicine”.

According to the United Kingdom’s Science Media Centre, one of the core principles of medical reporting is: “Don’t call something a ‘cure’ that is not a cure”. The “best available” evidence for hydroxychloroquine suggested that journalists needed to treat Raoult’s findings with caution.

Meanwhile, in San Francisco, a microbiologist who had made her name fighting scientific fraud had spotted a number of irregularities in Raoult’s paper. Posting on her blog on 24 March, Elisabeth Bik noted that peer review appeared to have taken no more than a day; the control and treatment group had significant differences; and the study was not randomised. Most concerningly, six of the study’s initial 26 patients treated with hydroxychloroquine had dropped out of the study and so were not counted in its results. Two of those six had been transferred to intensive care, one had died and one had stopped taking the medication due to nausea: “So four of the 26 treated patients were actually not recovering at all,” Bik wrote. In this context, Raoult’s “game over” results were looking much shakier.

On 3 April, the International Society of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy issued a statement that the Raoult study published in its journal “does not meet the Society’s expected standards”.

In the meantime, hydroxychloroquine was making a splash in Australia. On 17 March, news.com.au reported that “a team of Australian researchers say they’ve found a cure for the novel coronavirus and hope to have patients enrolled in a nationwide trial by the end of the month.”

Professor David Paterson from the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital (RBWH) and University of Queensland was paraphrased saying the two drugs – understood to be an HIV drug and hydroxychloroquine – had “wiped out the virus in test tubes”. One of the drugs, given to some of the first COVID-19 patients in Australia, “had already resulted in ‘disappearance of the virus’ and complete recovery”. Professor Paterson, it continued, said “it wasn’t a stretch to label the drugs ‘a treatment or a cure’.”

Professor Paterson appeared on commercial current affairs program The Project that evening to publicise hopes for a clinical trial. Asked whether describing the drug as a “treatment” was the same as calling it “a cure”, he responded: “Absolutely. We know that in the test tubes, and in the patients that have been studied so far, they’re able to recover and have no more evidence of virus in their system.”

The next day the University of Queensland issued a press release confirming that the clinical trials would proceed, with dozens of hospitals taking part. Professor Paterson was quoted describing the drugs as a “potential cure for all”. “Secret trial of AIDS, malaria medications ‘cures’ virus,” appeared one headline in The West Australian soon after.

Lyndal Byford, head of news and partnerships at the Australian Science Media Centre, was watching the early coverage of hydroxychloroquine with frustration. She’d been working with journalists from the earliest days of the pandemic, helping them sort good science from bad and cut through the hype.

Research institutions have a responsibility not to overhype single studies or overstate the strength of the evidence, Byford said. In the case of hydroxychloroquine and ivermectin, she recalled drugs being promoted “as cures for COVID at a stage where they had only been tested in petri dishes in labs, and some of them not even in animals”.

While not singling out any institution, Byford said she believed there was a direct relationship between these overstated claims and the misinformation that followed. “When you sort of trace it back, why did those drugs in particular become such a focus?” she said. “There were a lot of press releases coming out of very learned institutions and universities making those sorts of claims from scientists and research organisations who probably should have known better.”

When science reporting does get it wrong, she said, it’s often because the journalist relied on these press releases without seeking an independent opinion. Amid fierce competition for scarce government and philanthropic funds, she acknowledges there is little incentive for media officers to exercise restraint.

Overhyped press releases are a well-documented problem in science: in 2016, researchers analysed more than 500 press releases on biomedical and health-related science issued by peer-reviewed journals. Nearly a quarter of the press releases contained “more direct or explicit advice” than the journal paper and more than a fifth contained “exaggerated causal statements” about correlational research.

Guardian Australia’s medical reporter Melissa Davey was one of those who saw the University of Queensland press release and treated it with caution. “You just know that for there to be a “breakthrough” or a “cure”, it needs to have gone through so many rounds of clinical trials,” she told me. “Your alarm bells should be immediately going off.”

Davey was the first Australian journalist to report extensively on scientists’ reservations about hydroxychloroquine. She cited infectious disease experts who warned that it was far from a proven treatment, that it could take several months for conclusive results and that it had been known to cause heart damage and toxicity. “There are good reasons media do not normally report on these clinical trials until they are complete and have undergone peer-review,” she wrote.

A secret overseas mission

Meanwhile, Clive Palmer, mining billionaire, former member of parliament and leader of the populist United Australia Party (UAP), was greatly enthused by the drug’s potential. On 18 March a UAP press release announced he had donated AUS$1 million to the RBWH research fund for hydroxychloroquine trials.

On 23 March he went further, announcing that he would personally fund the acquisition or manufacture of one million courses of hydroxychloroquine to be placed on the national stockpile for free use by the Australian people. The health minister soon accepted the “generous” offer. It was reported that Mr Palmer had “mobilised a $50 million secret overseas mission” and “dispatched 10 people to secret locations across the globe and would bring back the highly sought-after drugs on a private jet.”

Within days, Palmer took out a two-page ad in The Australian announcing the move. It used the same language of the earliest media coverage, reporting that hydroxychloroquine and the HIV drug could “wipe out the virus in test tubes” and quoting Professor Paterson that “it was not a stretch to describe the drug as a cure.”

Davey reported that the university was “caught off guard” by the ads and had not been consulted about Professor Paterson’s inclusion. She noted that the university had since edited its press release to remove Professor Paterson’s description of the treatments as a “potential cure for all” and to add a clarifying statement. “I have never suggested these drugs be used before a trial establishes their efficacy,” Professor Paterson was quoted in the release. “Unfortunately, my comments have on some occasions been used out of context.”

I asked the University of Queensland about their decision to amend the media release. In a statement, it said that in those early months of the pandemic there was “a voracious appetite for news that would provide hope”. The media release was amended because the university was “uncomfortable with the way the story was being reported” and wanted to “prevent misrepresentation”. Hydroxychloroquine had shown promise in lab testing and “there was a clear sense of urgency to understand the virus [and] possible treatments.”

Clive Palmer remained bullish about the drug’s prospects. In late April, he placed a three-page advertisement in News Corp newspapers where he announced he had bought 32.9 million doses of the drug. He suggested its use in Australian hospitals was responsible for the country’s low death rate and flattening curve, a claim RMIT ABC Fact Check labelled “baseless.”

Despite warnings about the paucity of evidence, headlines in Australian media between March and August 2020 continued to tout hydroxychloroquine as a “cure”: “Australia to get virus ‘miracle drug’ soon” (News.com), “Scripts for hyped COVID-19 cure restricted” (Daily Telegraph), “Aussies import Trump's virus 'cure' drug” (The Canberra Times), and “Virus ‘cure’ imports at record rate” (The Courier Mail).

The overhyped media coverage was indeed capturing public attention. In late March, the federal government was warned that patients who needed the drug for other conditions were missing out amid shortages. On 4 April the ABC reported that it had “been flooded with audience questions about … whether hydroxychloroquine could provide a cure”. By May, more than 6,000 illegally-imported tablets had been seized at the border.

Journalists and editors were undoubtedly working in good faith and at great speed as they scrambled to keep audiences informed. But media academics warn that “problematic journalism” – whether the result of poor research or sloppy verification or “sensationalising that exaggerates for effect” – can allow misinformation “to originate in or leak into the real news system”. Much of the misinformation in medical reporting happens when “initial findings” are overhyped and then fail to stand up in subsequent meta-analyses; one study found that journalists rarely inform the public when these initial findings they reported are later overturned.

One of the biggest retractions in modern history

There were also examples of best practice in science journalism among those reporting on early hydroxychloroquine science. These stories looked closely at how research was conducted, evaluated study designs, explained the importance of sample sizes and contextualised new findings within the existing body of research; all hallmarks of best practice.

“A large study by the WHO should have more reliable results in the coming months,” ABC’s science writers Tegan Taylor and Ariel Bogle wrote. Nine Newspapers’ science writer Liam Mannix wrote: “Most new drugs that show promise as potential COVID-19 cures will not end up working, scientists caution, and many are toxic.” Lyndal Byford told Mannix that claims about alternative treatments as a “breakthrough” or “the cure for COVID-19” could undermine public trust in science: “There is a fine line between hope and hype.”

As the hydroxychloroquine ‘infodemic’ raged, these specialist science reporters showed how news outlets can help combat and even inoculate the audience against misinformation.

As Ed Yong, who won a Pulitzer Prize for his reporting on COVID-19, put it: “The best science writers learn that science is not a procession of facts and breakthroughs, but an erratic stumble toward gradually diminished uncertainty.”

“Some scientists make the mistake of thinking that journalists are their partners in getting information about science out there, and that’s a misunderstanding,” reflected the New York Times science reporter Apoorva Mandavilli. “Journalists are not scientists’ friends, nor their partners. We’re actually there to hold them accountable.”

Misinformation can prosper “in and about science” itself. More than 74,000 papers COVID-19 papers were listed in the biomedical library PubMed in the first year of the pandemic alone. In scientists’ rush to carry out and communicate their research as soon as possible, rigour sometimes became a casualty of speed. The best science reporters played a dual role during this time: explaining and helping their audience build trust in “good science”; while interrogating, uncovering and exposing “bad science” – and even fraud – when it occurred.

“It's a tight, difficult line to walk as a medical reporter,” Davey told me. “On one hand, you want the general public to trust the science and believe science and rely on good science. On the other hand, you're saying, ‘There are people who exploit science out there. There are really prestigious, so-called safe journals that get it wrong.’”

Davey urges reporters to be honest and transparent: “You have to go to that extra level [where you] explain to your readers, ‘Here's why you can trust these organisations, here’s why they sometimes get it wrong, but here’s why you can still trust this process’,” she said.

Davey’s commitment to scrutinising science and holding scientists accountable triggered “one of the biggest retractions in modern history”.

On 22 May 2020, The Lancet published a peer-reviewed study based on data from 96,000 patients in 671 hospitals that found an increased rate of death and heart problems in patients treated with the drug. The fallout was immediate: the World Health Organisation and research bodies around the world called a halt to trials of the drug.

But in Melbourne, Davey had become aware of some irregularities with the data the study used. She spoke to an epidemiologist who made a “throwaway comment [that] he wasn't quite sure how they got [the data].” When she probed further, he said he wasn’t aware of any hospital reporting systems that would have recorded it.

Davey made more calls; senior epidemiologists in Victoria and New South Wales told her they didn’t believe the data existed. ‘OK, that’s the story,’ she recalled thinking. As she scoured Twitter and science blogs, she saw other scientists raising questions about their country’s data. “Errors happen all the time,” she told me. “But when data doesn’t add up and you can't figure out how it was even achieved, usually it’s a red flag for much bigger problems with the story.”

Davey published her findings on 27 May: the death and hospitalisation rates reported by The Lancet, which had been provided by a private “healthcare data analytics” firm, Surgisphere, didn’t match up with the numbers recorded by Johns Hopkins University; and it wasn’t clear how the Australian data was obtained in the first place, given it isn’t publicly available. Davey had contacted seven Australian hospitals; none had provided their data to Surgisphere. The Lancet told her it had asked the authors to provide clarification; one of the co-authors said he was also seeking these answers from Surgisphere with “the utmost urgency”.

When Surgisphere refused to provide the full data set for independent audit, the study’s co-authors asked for the study to be retracted, saying they could “no longer vouch for the veracity of the primary data sources”. The prestigious New England Journal of Medicine soon followed suit, retracting a separate COVID-19 paper also based on Surgisphere data.

It was the most high-profile but far from the only example of science “getting it wrong” during the pandemic. In a field where career progression depends on getting published and being frequently cited, scientists have strong incentives to deliver dramatic, eye-catching results. As of July 2022, more than 240 COVID-19 scientific papers have been retracted or withdrawn.

The four horsemen of irreproducibility

Journalists need to be aware that a number of shoddy research practices can compromise outcomes. These were famously described by Professor of Neuropsychology Dorothy Bishop as the “four horsemen of irreproducibility”: P-hacking (where only “statistically significant” analyses are reported); HARKing (“hypothesising after results are known”); publication bias (where researchers and journals are less likely to publish studies that show no impact); and low statistical power (for example, where a study has a small sample size).

Journalists should also be aware that poor-quality science can also find its way into “predatory journals” which offer “minimal or non-existent” peer review and exist purely to extract publication fees.

Exposing examples of scientific misconduct is a fundamental duty of science journalism. The ABC's Sophie Scott, for example, chose not to cover the now-retracted Lancet paper linking the MMR vaccine to autism because its problems were apparent early on; instead she worked on a series of stories which highlighted these flaws and refuted the findings. Other times she’s uncovered outright scientific fraud. “I don't think it undermines science as a whole,” she said. “It’s an important part of keeping people accountable.”

In fact Nisbet and Fahy argue that this work of “knowledge brokers” like Davey and Scott can actually increase public trust in the work of science. Journalists covering COVID-19 also needed to know whether the doctors or scientists they were seeking comment from were recognised experts in their field. The pandemic had seen a flood of “epistemic trespassing” where “thinkers who have competence or expertise to make good judgments in one field” move into an area outside their field of specialisation. In Melbourne, for example, a group of doctors – described as “general practitioners, urologists, psychiatrists and surgeons” – were profiled in local media reports advocating for hydroxychloroquine and ivermectin.

Sometimes news organisations face a dilemma covering scientists recognised as specialists but whose views sit outside the mainstream. Retired immunologist Robert Clancy was an advocate for hydroxychloroquine frequently cited by Australian MP Craig Kelly. In February 2021, Sydney Morning Herald published an opinion piece by Clancy touting the drug’s benefits alongside an opinion piece by epidemiologist Catherine Bennett arguing there was insufficient evidence.

The effect was to falsely suggest an evenly balanced debate within the scientific community. To address this, the newspaper added a note from Liam Mannix to the op-eds stating that “[t]he evidence shows hydroxychloroquine and ivermectin are not effective in treating or preventing COVID-19.” The University of Newcastle issued a statement that it “does not consider Robert Clancy a subject matter expert on COVID-19.”

Sometimes there’s a “grain of truth” in the perspectives of outlier scientists which should be acknowledged, according to science communication expert Professor Sujatha Raman, “but that doesn't mean that the overall conclusion they're drawing is the one that we should advocate for.”

The story could have ended there

By August 2020, the scientific community’s hopes for hydroxychloroquine had dimmed.

The story might have ended there: a matter of clinical judgement by scientists who looked at the best available evidence and found it wanting. Instead, the story was kept alive by a fierce and increasingly bitter public debate that revealed what can happen when belief in science becomes a marker of political identity.

The entry of polarising political figures into the hydroxychloroquine debate set the stage for politicisation early on. It led to people “reflexively adopting positions supported by in-party elites and opposing those offered by out-party elites”.

A number of conservative newspaper columnists campaigned for Australian health authorities to authorise use of the drug. They often suggested the resistance to the drug was driven by animosity towards President Trump.

Hydroxychloroquine was also heavily promoted by commentators on Australia’s Sky News Australia, as documented by ABC’s Media Watch in April 2020, October 2020 and February 2021. In August 2021, YouTube removed Sky News Australia from its platform for seven days for violating its “medical misinformation” policies, saying it didn’t allow content “that encourages people to use hydroxychloroquine or ivermectin to treat or prevent the virus”.

In August 2020, another Australian political figure entered the fractious public debate over the drug, this time from within the federal government’s own ranks. Craig Kelly had been a member of parliament since 2010. He had a long record of questioning climate science and his large social media following saw him dubbed “one of Australia's most influential politicians on Facebook”.

In early August, he posted about hydroxychloroquine on Facebook 18 times over two days: “[C]ontinuing to ban this drug is negligent … Australian lives should not be a risk because of Trump Derangement Syndrome.” The Daily Telegraph reported that Kelly claimed the World Health Organisation had “faked” the now-retracted Lancet study.

“There is a special place in hell awaiting those that have been part of the war on hydroxychloroquine for political reasons,” Kelly claimed. “They have the blood of tens of thousands on their hands.”

Australia was being “governed by medical bureaucrats that are part of a mad, insane cult,” he told anti-vaccine protestors in Melbourne. Having been counselled by the Prime Minister to heed expert medical advice, he quit the government in February 2021. Six months later, he accepted an offer to become leader of Palmer’s United Australia Party.

Look for “the tipping point”

Journalists and news organisations faced a dilemma about what treatment to give views expressed by politicians such as Craig Kelly which run counter to the best available scientific evidence.

Misinformation researchers have long warned about the dangers of amplifying false claims: “Reporting too early gives unnecessary oxygen to rumours or misleading content that might otherwise fade away,” said Claire Wardle from the NGO First Draft News. “Reporting too late means the falsehood takes hold and there’s really nothing to do to stop it.”

It’s all the more complicated by the fact many fringe actors actively seek mainstream media attention and celebrate negative coverage as further evidence “they are close to uncovering some deeper truth.”

But that calculation changes when a false claim is circulated by a politician or high-profile public figure. “It's already way past the tipping point,” First Draft News’ Asia Pacific researcher Stevie Zhang told me.

Indeed, there is evidence that “top-down misinformation” shared by politicians, celebrities and other public figures has wide currency; the Reuters Institute surveyed 225 pieces of misinformation early in the pandemic and found misinformation by public figures made up just one fifth of the sample but accounted for more than two thirds of total social media engagement.

For this reason, many misinformation researchers urge journalists to do more to integrate fact-checking of public figures into their daily reporting.

The epilogue

There are a few notable postscripts to the story of hydroxychloroquine in Australia.

In July 2021, a group of researchers suggested that the media hype surrounding the drug may have distorted Australia’s research priorities. They noted there were six simultaneous trials funded for hydroxychloroquine in the first year of the pandemic and none for public health communication, community transmission prevention or Long COVID symptoms. “Extensive media coverage and public opinion may have influenced prioritisation of interventions that were not particularly promising," the authors concluded.

In October 2021, one tonne of the hydroxychloroquine purchased by Clive Palmer was destroyed. It had sat unclaimed in a Melbourne warehouse for eight months, the result of a standoff between Palmer’s foundation and the federal government.

Palmer continued to tout hydroxychloroquine’s benefits. In February 2022 he contracted COVID-19. Sky News Australia reported his claim a team of US doctors had “fast tracked” him onto drug trials so he could be treated with hydroxychloroquine and ivermectin.

The United Australia Party ran an election campaign promising to allow “alternative treatments to COVID-19 (including anti-virals) that have shown extraordinary success where administered in many overseas countries.” Despite the most expensive campaign in Australian history, the party’s primary vote failed to climb above 5% in the May 2022 election. Craig Kelly won fewer than 8% of first preference votes in his seat.

By December 2021, the 6% of Australians who were unvaccinated made up half the patients who had been in intensive care over the previous six months. “There are the family members, pressuring doctors to prescribe bogus medicines they have heard about online,” Guardian Australia reported, “‘trying to go toe-to-toe’ over the phone with the registrar, pushing some unproven treatment.” Scientific misinformation had real and tragic effects.