In this piece

How journalists can hold algorithms accountable in India – and beyond

An iris scan for Aadhaar, the biometric ID now used across many Indian services from rations to payments. Credit: Reuters/Amit Dave

In this piece

Algorithms in welfare systems | Algorithms of surveillance | Algorithms and workers’ rights | The politics of technology | Algorithmic accountability journalism | For those without the time to read, a brief summary:In India, algorithms now sit between people and their most basic rights. They decide who gets subsidised food, daily wages, pensions and disability allowances; in the gig economy, they act as de facto managers.

The promise was efficiency and inclusion. The reality, too often, is exclusion without remedy.

Consider the example of a national app for workers under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA). It demands two geo-tagged selfies a day. Miss an upload – patchy signal, shared handset, ageing device – and you don’t get paid.

When LibTech India’s Chakradhar Buddha filed a Right to Information (RTI) request asking whether any pilot preceded the roll-out, the initial answer was no. Months later, a token pilot appeared at a single site. In Buddha’s words: “It’s like you have to prove your chastity every day.”

Algorithms in welfare systems

The pattern described above repeats in other welfare databases. In Haryana, a family-ID system meant to streamline benefits erroneously marked living people as “dead”, cutting them off overnight. In Telangana, a data-matching stack wrongly denied subsidised rations to thousands.

On paper, digitisation removes “middlemen”; in practice, it replaces them – with enrolment agents, help-desk operators and opaque rules no one can see.

Algorithms of surveillance

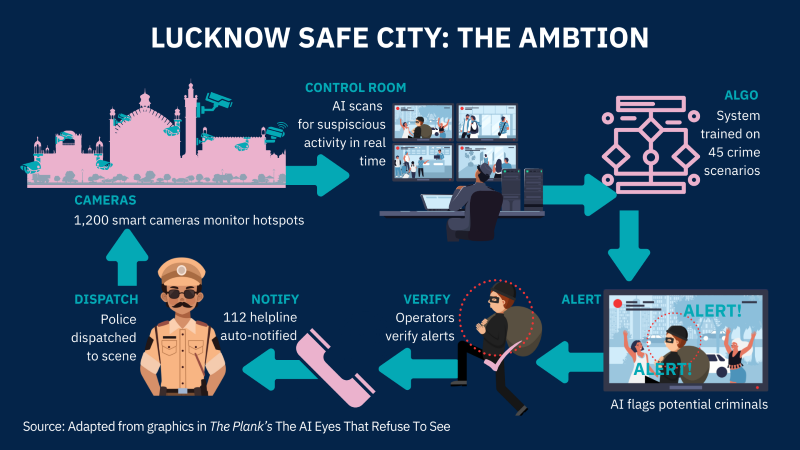

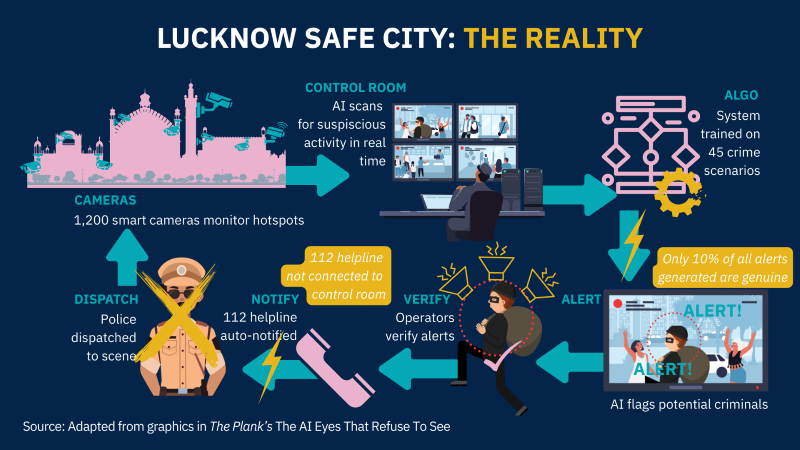

In cities, “safety tech” promised protection but now delivers surveillance. An AI “emotion-recognition” pilot in Lucknow was scrapped after scepticism about its accuracy – but a broader camera network and command centre carried on.

Technology researcher Disha Verma recalled asking the vendor what happens to all those faces. The answer: they strengthen the model for future clients. The women the system claimed to protect? Not in the room when decisions were made.

Algorithms and workers’ rights

Meanwhile, the apps managing gig work reward the myth of flexibility while controlling access to income. Drivers locked out by facial recognition after minor appearance changes, beauty workers auto-assigned jobs they didn’t choose, delivery riders whose health insurance is tied to shifting performance targets. These are all systems that transfer risk downward and reward upward, while hiding decision-making.

The politics of technology

Why does this keep happening? Partly because we treat technology as a virtue rather than a policy choice. As Apar Gupta, lawyer and founder-director of the Internet Freedom Foundation, argues, fundamental rights cannot be traded for access to welfare: consent, dignity and safeguards are not luxuries. Yet across the political spectrum, digitisation is embraced as an unquestioned good. “The minute you say someone is a technologist,” Gupta noted, “there’s an implicit value [that] this person is not corrupt, this person works hard, this person has set up things which are of value – of economic value – and they’re doing a favour by being in public service.” But expertise is not a substitute for accountability.

It doesn’t help that India now exports its digital public infrastructure model, cheered on by multilateral bodies like the United Nations and World Bank who favour digital ID, payments and data-exchange as development tools.

The speed of scale is impressive, but our scrutiny of the resulting exclusions has lagged behind. As AI reporter Karen Hao told me: early exclusions are the canary in the coalmine – the first visible symptoms of deeper design and governance failures.

Algorithmic accountability journalism

The good news: journalism works. The work of eight journalists and researchers highlighted in this fellowship project all yield lessons that will be useful to any journalism looking to do more stories that hold tech power to account.

Gabriel Geiger, investigative journalist at Lighthouse Reports who specialises in surveillance and algorithmic accountability reporting, shared his step-by-step guide in the full project, while other journalists and researchers summarise their own lessons in algorithmic accountability at the end of each section.

For those without the time to read, a brief summary:

Start with people. Sit with the communities who live inside these systems. Map what the rule says should happen, then document what actually does.

Follow the paper trail. RTIs/FOIs for contracts, statements of work, data-protection and impact assessments, user manuals and evaluation reports. Procurement is a goldmine.

Ask technical questions. Which data? Which rules or models? What are the error rates and appeal paths? If source code is out of reach, evaluation artefacts and rule tables still reveal a lot.

Build coalitions. Pair reporters with lawyers, academics and civil-society groups; use client case files to trace individual decisions; crowdsource where data is missing.

Language matters, too. LibTech India deliberately refers to people as rightsholders, not “beneficiaries”: welfare is a legal entitlement, not charity. And gig workers should be recognised – in law and practice – as workers, not users of an app.

This is not an argument against technology; it’s a case for rights-centred design. Consult before rollout. Run real pilots and process audits. Keep an analogue fallback when systems fail. Publish error and appeal rates. Limit purpose for sensitive data. Enable independent audits – including of code – and provide time-bound redress when technology fails.

India ranked 151st of 180 in the 2025 World Press Freedom Index. That many of the most important stories here came from independent, grant-supported reporting is no accident. But the methods are repeatable by those working in legacy media, and by journalists outside of India.

With persistence and partnerships, we can make invisible systems legible – and push them to serve the people they govern.

To read Karen's full project, download the PDF below.