In this piece

How free is Ghana’s media?

People read papers in Ghana's capital, Accra. The industry has boomed since the 1992 constitution introduced freedom of the media. But how free is it today? REUTERS/Yaw Bibini

In this piece

Ghana’s president Nana Akufo-Addo stood before representatives of the world’s news media at a sparkling awards dinner on the evening of May 3, 2018.

They had come together in the Ghanaian capital Accra to mark World Press Freedom Day. The West African nation was the number one African nation on the World Press Freedom Index that year.

“I will say again that I much prefer the noisy, boisterous, sometimes scurrilous media of today, to the monotonous, praise-singing, sycophantic one of yesteryear,” President Akufo-Addo told those assembled for the Press Freedom awards dinner.

Barely hours after this speech, a member of the president’s political party, the New Patriotic Party (NPP), assaulted a journalist at the party’s headquarters.

The NPP would not condemn the event and the government would not comment until journalists and media outlets threatened to stop covering NPP events. The government’s handling of this incident reflects the disconnect between Ghana’s free media status and the reality of journalistic safety.

Ever since freedom of the media was enshrined in Chapter 12 of the nation’s 1992 constitution, it has flourished. Today, you will find a vibrant media environment where journalists expose corruption, highlight incompetence and crime, and demand a measure of accountability from the powerful.

At a local governance level, elected and appointed officials are kept on their toes by community members who call and text into radio programs. In many ways, private media – especially radio – has become a tool of democratic participation for large sections of the population.

But beneath this veneer of freedom, there are still challenges.

In the two years since that awards dinner, investigative reporter Ahmed Suale was shot and killed in broad daylight in Accra. He had been a lead investigator for Tiger Eye Private Investigations.

His best known work had come six months before his death: a film exposing corruption in Ghanaian football that led to the dissolution of the Ghana Football Association. Kennedy Agyapong, an MP, revealed Suale's identity on TV and called on his supporters to attack him.

A year after the murder, Modern Ghana editor Emmanuel Ajarfor Abugri and reporter Emmanuel Yeboah Britwum were abducted from their offices and detained by national security officials who searched their phones and laptops in an attempt to determine the source of a story about the national security boss.

By 2019, the Media Foundation for West Africa recorded over 31 attacks on 40 journalists over an 18-month period.

We know from the example of other countries that unchecked violence against journalists emboldens attackers and undermines freedom of the media.

The NPP may pride itself on being the party that repealed the Criminal Libel Law, freeing Ghanaians from what the President Akufo-Addo called “unnecessary self-censorship”. Yet journalists continue to be attacked both on- and offline, often by supporters of dominant political parties and agents of the state. These attacks have often gone un-investigated and unpunished.

Like so many freedoms, Ghana’s press freedoms are fragile and not guaranteed if we do not pay attention to these key, growing detractors.

Intimidation and threat

In conversations with my Ghanaian colleagues, some expressed fear of reporting on certain issues and groups. Others said they have had to overlook certain stories or seek permission from state agencies.

Fear of intimidation or physical harm informs which stories they tell. More broadly, it has affected their capacity to do their work and provide the public with reliable information.

“I do worry occasionally about my safety as a journalist because I am not aware of any clear-cut policies by either my media house or the government to offer any protection to journalists,” said one journalist, who asked not to be named for fear of reprisal. What deepened their fear the most, they said, is that “sometimes the government itself and some state agencies, like the police and military, can be used to intimidate journalists”.

Recalling an incident with a story about the Ghana Armed Forces, they continued: “Sources in the army called to warn me of possible violent attacks against me if I broke the story. I broke the story anyway, but not [until] I received a verbal assurance from the director of Public Affairs of the Ghana Armed Forces about my safety. I was scared about making the publication due to our history with the military. [Since then], I always seek assurances from any concerned security agency about my safety before publishing a story about them.”

Stifled sources

Journalists are not the only group who censor themselves due to the threat of violence, harassment or intimidation: Experts, business owners, and public sector workers such as teachers, nurses, and university lecturers often decline to speak to journalists for fear of victimization and possible job loss. Business owners and other private sector people have lost contracts as a result of speaking to the press, while public sector workers face transfers and other sanctions.

Consequently, the same group of privileged voices are trotted out to shape national conversations in the Ghanaian media: mostly men, often partisan, and from the educated and political class.

In fact, a Media Foundation for West Africa report found that “male discussants consistently dominated radio discussions” with as much as 83% share of voice. Large sections of the population – women, persons living with disabilities, and people living outside the capital – are excluded and their concerns are not prioritised.

This lack of plurality means Ghanaian mainstream media is dominated by a narrow set of ideas (often pro-business, neoliberal and capitalist). Even discussions and stories about marginalised groups are dominated by political class and elites (increasingly the lawyer class).

Instead of faithful and independent accounts of events and issues, stories are reduced to he-said/he-said arguments between the two major parties. Journalists are unable to provide the full context of specific stories when those affected are too afraid to go on record – particularly concerning high-profile stories.

For example, Ghanaians still don’t know what motivated the government to cancel a power agreement which in turn lost the country a $190 million US government grant.

The inability of journalists to verify leaked documents and the unwillingness of some media companies to use verifiable information meant this story, like many scandals, was reduced to political entertainment.

In cases where investigations are conducted, they are often superficial and don’t include names and details of people involved. In the worst cases, journalists wait for members of the elite class to tell them what issues to adopt.

During the banking crisis of 2017 and 2018 (when seven indigenous banks collapsed), despite reports and evidence suggesting criminal conduct, journalists were hesitant to describe what happened as criminal until some elite lawyers made the pronouncement. Typically, less powerful offenders are swiftly labelled as thugs.

Impact of media ownership

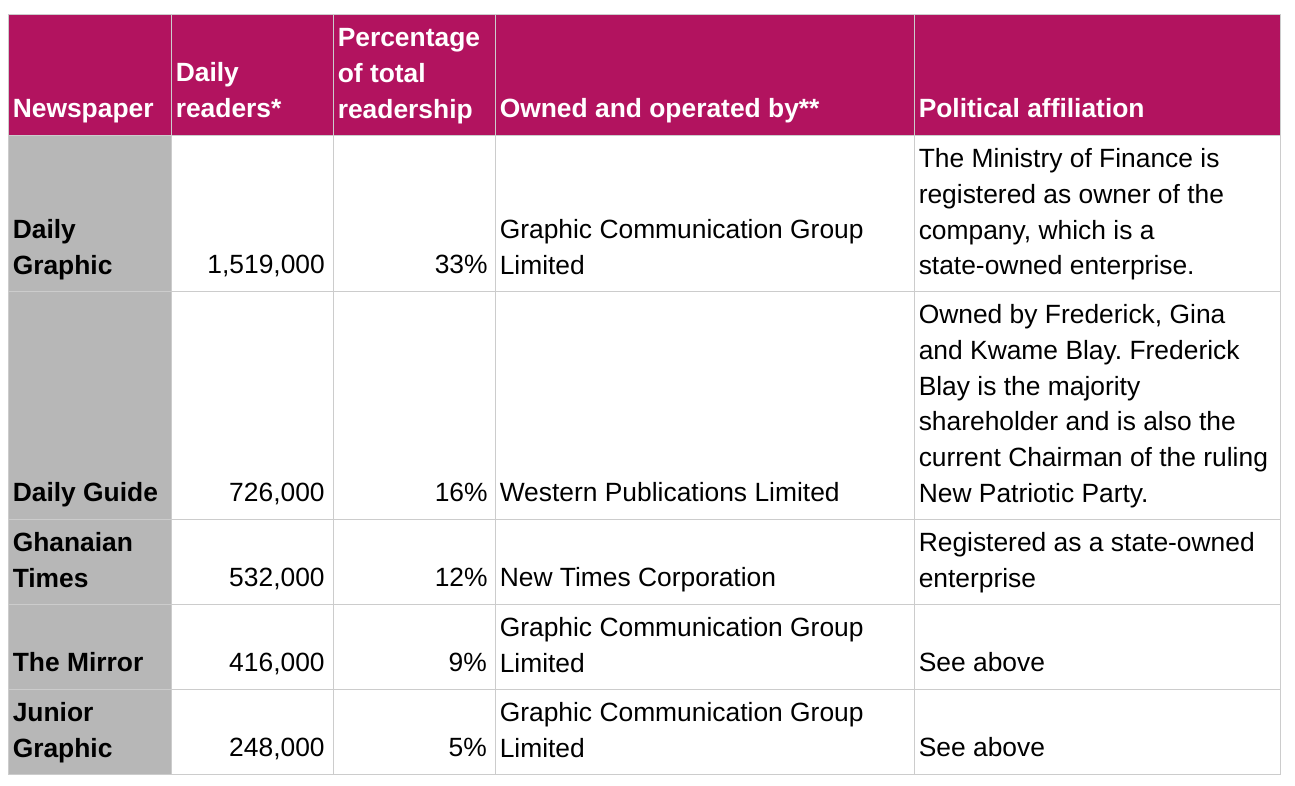

One third of all media outlets in the country are owned by politicians or people affiliated with the dominant political parties, according to the Media Ownership Monitor Ghana. And much of the content they produce – particularly news and current affairs – is partisan.

It is easy to see where these companies sit on the political spectrum by analysing their content.

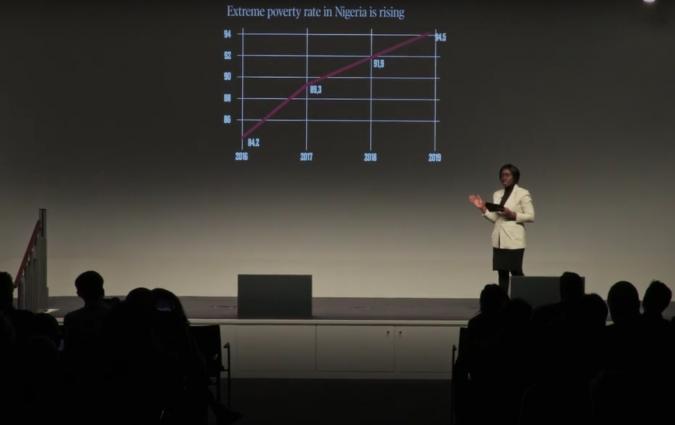

An overview of ownership of five of the most-read newspapers, accounting for nearly 80% of daily readership, illustrates how dire the situation is.

Journalists at these outlets are typically not allowed to be openly critical of people associated with the outlet or the owner. Media owners can silence journalists seen to be too critical, kill stories, and even exclude certain topics from their platform.

In these newsrooms, journalists may be called upon to suppress or overlook damaging stories and focus on sensational stories about opponents. Editors are pressured to tweak headlines and narratives, and ignore scandalous stories involving close friends.

To avoid conflict or loss of access, editors and journalists resort to superficial “both sides journalism” by reporting NPP/NDC partisan truths. In this way, we do not provide the public with reliable information and conclusive ‘truths’ because that would require us exposing the allies of media owners. As such, we’ve become unwitting participants of the collective open secret-keeping culture.

It is not for lack of access that we find ourselves in this position: there is almost nothing that happens in Ghana, particularly in the corridors of power, that journalists do not know about. They often know why contracts are awarded and cancelled by the government. They know which group in the governing party profits from contracts and whose palm investors and businesspeople grease before securing access to state contracts. They know which officials own properties they cannot afford on their government salaries in different countries. They can name all the politicians who paid for votes during the primaries of the two parties. They understand why Ghana’s education and health outcomes are so poor, even though the country spends so much on these sectors.

Yet none of these stories transition into well-researched, well-sourced news stories. The fear and intimidation at play is so effective that politicians do not even hide what they do. This system of open secrets speaks to the ability of power to keep journalists in line.

There is one missing access level that would work to balance this power: After 18 years in parliament, Ghana is still yet to operationalise the Freedom of Information Law that was passed in March 2019, which is why officials can decline to share information, data and public documentation.

In instances where people have gone to court to compel the government to release information to the public, it has simply refused to do so. And so the common refrain from politicians when certain stories become public is to ask: “Where is your evidence?”

These are stories that citizens need to know about to make informed decisions, but many remain within the “whisper channels”.

A struggling business model

The situation is further complicated by the media’s financial and logistical constraints. Many private media companies are, in the words of IREX report 2012 “poorly capitalized, one-man-owned endeavors in which the proprietor is often also a pseudo-politician. The duties of the other staff, if there are any, are not well defined. The proprietor is the editor-in-chief, sub-editor, and business and financial manager.”

Those findings remain true in 2020: a single journalist may fill three different roles in a newsroom: anchor, reporter and producer in one. Others are assigned multiple daily beats: covering the court, the police and politics.

Aside from business and sports reporters, very few journalists are afforded the chance to become subject matter specialists. Even correspondents are stretched, and given as many as 16 regions to report from simultaneously.

And, like their colleagues in Accra, regional correspondents have to use their own equipment and resources: recording interviews with their phones, working on their personal laptops and paying their own way to places.

“It felt like the company was doing journalists a favour when we requested [...] materials to work with. We were asked to use our own phones and find our own means of getting to news sites if the company's resources weren't enough,” said a 34-year-old female journalist in Accra.

In this environment, journalists do not have the space, time or the resources to dig deep and produce in-depth and nuanced longform pieces, documentaries and features. This is why, to understand any story in Ghana, one should read across multiple news websites.

Underpaid and under influence

In addition to being time poor and under-resourced, Ghanaian journalists are also often underpaid. Media companies are not transparent about salaries, but anecdotal evidence is that some journalists are paid below the minimum wage (U.S. $2.16 per day). Others report instances where salaries are delayed for months without explanation.

In conversations, colleagues spoke about being unable to access healthcare services because they cannot afford to seek help on their meagre salaries, and the media companies do not provide healthcare. Others complain about struggling to pay rent, transportation and getting through the month on their salaries. And it is worth noting that while wages are generally low in the industry, women journalists are paid far less than their male counterparts even while facing the added pressure of external and internal sexual harassment.

As a result of low wages, a number of journalists come to depend on inducements such as “soli”, industry jargon for a “solidarity” payment made to reporters by interested parties for publicity. In the end, some journalists are effectively doubling as public relations officials for companies and individuals.

“The meager pay significantly impacts my work because I am forced to look for other alternatives to complement my finances and often venture into using the media platform as a PR tool for private companies who will compensate you well enough not to reject their offers,” said a 35-year-old male journalist at a private radio station in Accra.

Under these conditions, business “journalism” becomes an extension of corporate marketing. Journalists forego independent investigations and rigorous reporting, and instead favour whoever offers the best rate. They may even suppress stories and facts about powerful people and companies willing to pay.

As one journalist put it, media companies tend to turn a blind eye to the impact of soli and other forms of inducements. “Because organisations are not compensating as fairly as they should, they […] indulge reporters who focus on the PR stuff. It's like an unwritten perk of the job.”

These low wages and poor working conditions also results in a high turnover in newsrooms across Ghana. Journalists, particularly those who manage to rise to the top, often leave after a few years for well-paying sectors. This leads to a “brain-drain” of experienced journalists who would otherwise provide context, analysis and support for inexperienced journalists.

As one 27-year-old journalist from Accra put it: “I do not think I am adequately compensated for the volume of work I put in at my workplace, and that is one of the basis for a rethink of my career choice or at least rethink of the space I currently work in. But, again, I recognise that this situation cuts across the entire media space in Ghana; many people are underpaid.”

Combine low pay with high risk, and the outlook becomes bleak. How many business journalists would be willing to investigate and report the corrupt or harmful dealings of a company when they have been taking soli from them for years? Is it any wonder then that business journalists failed to predict the banking crisis of 2017? How many political journalists would be able to expose corruption or scandals involving politicians who contributed to their rent? Or be critical of the political party that funded their education?

Those entrusted with such an important societal function should not be earning less than minimum wage. And, equally troubling, they should not be so fearful of discussing these realities in public. If journalists do not feel safe enough to publicly discuss their conditions of work, how can they tell the truth about other sectors?

Covert interference

In addition to the challenges listed above, there are other forms of government interference that undermine media freedom. The constitution bars governments from interfering with the work of the media, but that has not stopped successive Ghanaian governments from using covert tools.

The NPP government appears to have taken oppressive tactics up a notch with the closure of opposition radio stations for alleged “non-payment of taxes”. The government has been accused of acquiring surveillance equipment that some fear may be used to hack electronic gadgets belonging to journalists.

Supporters of the two major parties are paid to call into radio programs to help shape the public perception of their parties, as well as harass journalists critical of their parties online. Journalists report having to censor themselves on radio, TV and online for this reason.

Trust undermined

Little wonder then that 72% of Ghanaians said the media is not free from government control in a recent Afrobarometer survey. This partly helps to explain the sharp decline in public support for the media recorded in 2017.

Like presidents before him, President Akufo-Addo may say all the right things in support of media freedom, but it is manifestly evident that Ghanaians are not fooled.

Ghanaians may not know all the challenges that journalists face in their work or how the media ecosystem works, but they have noticed attempts by the governments to control the media. These attempts act to undermine the public’s trust in the media, further curbing its ability to ensure the electorate is informed. As Freedom House says: “the ability of journalists to report freely on matters of public interest is a crucial indicator of democracy”.

All of these points call into question Ghana's status as a democractic country with the freest media environment. Can the media be considered one of the freest even though Ghanaian journalists are unable to tell the whole truth?

The way out

Not all journalists in the country are corrupt, and not all media houses have been captured. There are journalists and entire newsrooms that continue to push to expose corruption and rot in high places.

There are freelance journalists shining a light on human rights and good governance stories. Some of these, ignored by the mainstream media, have created podcasts and started news websites to reach audiences of their own.

Organisations like the Ghana Centre for Democratic Governance (CDD) and the Media Foundation for West Africa collaborate with media outlets to produce specific programs focused on transparency and accountability.

But these alone cannot fix the systemic problems that impede media freedom. There are no simple solutions to the problems that plague Ghanaian media.

I take hope from research reports, like the Reuters Institute’s Fighting Words: Journalism Under Assault in Central and Eastern Europe, where Meera Selva details how media companies and journalists in other countries are pushing back.

For a start, journalists can rally behind those who come under attack from the government and other agencies. Save for perfunctory comments, journalists often ignore attacks on other journalists from different outlets, leaving room for more of the same. We ought to extend solidarity to every colleague who comes under attack, no matter who employs them or how we view their work.

While doing so, we must learn to hold ourselves and our media companies accountable and to ethical and journalistic standards. Any notion that journalists should politely ignore the glaring mistakes of their peers and other outlets undermines trust in the media and leaves us open to failure.

Donors and investors in media development should focus their investments in independent local media outlets to ensure long-term sustainability of the marketplace.

And finally, the Ghana Journalism Association has a huge role to play. It can to prioritise the interests of journalists by demanding fair wages, job security and improved work conditions for them.

State media workers are unionized, but journalists who work for private companies must be allowed to unionize too. The GJA should end this practice of exclusion that leaves many journalists vulnerable to bribes and other inducements.

During her time at the Reuters Institute, Nana Ama also undertook a podcast series Inside the Media with fellow Kohei Tsuji, in which they explored five questions faced by the media. Among these episodes: