Poverty-eradicating financial journalism: For this Nigerian, it’s like learning to ride a bike

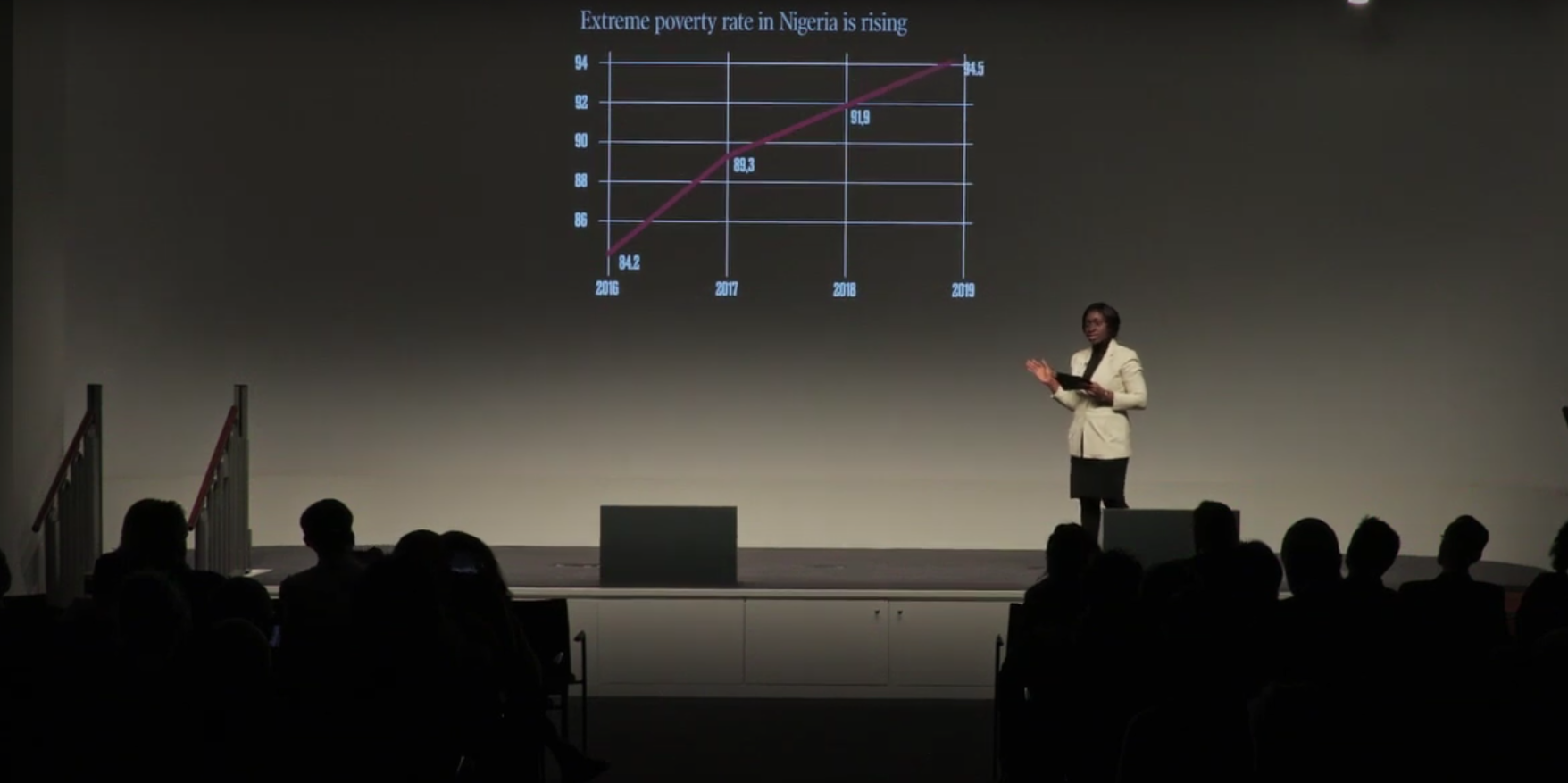

Adesola Akindele-Afolabi delivering her final keynote at the Reuters Institute in 2019

I realised something awful during my time at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism: for the past five years I’d spent my days doing the wrong things and pursuing the wrong goals.

At the time, I was working as a finance journalist at business a.m. – a weekly newspaper in Nigeria’s commercial capital, Lagos. But over the course of my career, my articles had been focused on the wrong audience; I’d been ignoring the people who needed me the most.

My audience had been finance regulators, CEOs of banks, listed companies, insurance firms. I’d also been writing for corporate communication executives, stock brokers, investors... These are the top elite of Nigeria’s business society: men in suits.

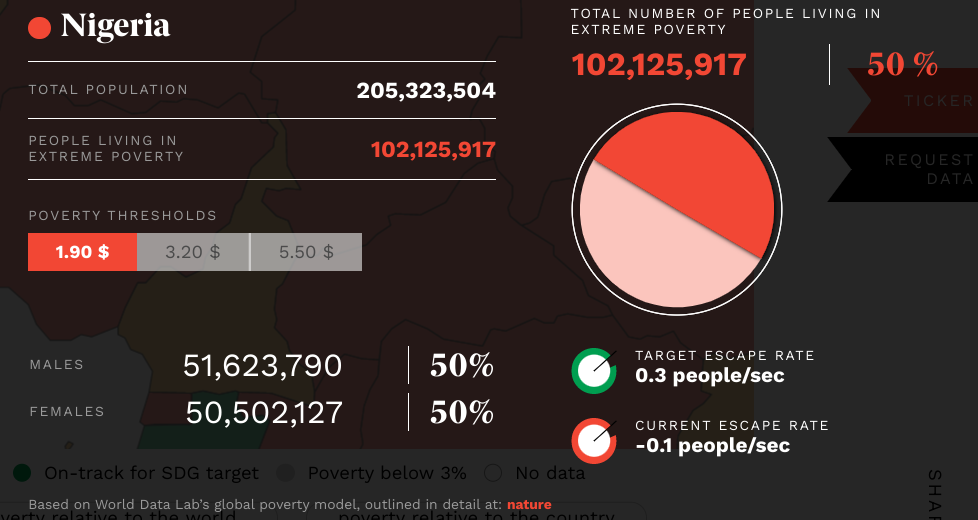

My country is the poverty capital of the world. According to the World Poverty Clock, more than 10 million Nigerians over the past three years have fallen into extreme poverty. To put it another way: this means five Nigerians fall into extreme poverty every minute.

As a little girl, I tasted poverty in its raw form. The realisation of how vulnerable our finances were as a family started when my dad – who was the first born of his family and the breadwinner – lost his job.

I had to drop out of secondary school. I eventually gained admission into a government-owned tuition-free school, but we had to pay for books, school uniforms, provisions and so on. It was a struggle. Luckily, I have a mother who trained each of her five children on efficient financial habits – even when resources were scarce.

So with my own experience of navigating the waves of poverty, and the evident degrading economic situation of Nigeria, I started to ask myself: what am I doing to change this narrative? What is my true responsibility as a financial journalist and an economist?

My audience at that time was made up of the 2% of the country’s nearly 200 million people who had savings of $1,400 or more in their bank accounts.

The people who actually needed financial information are the >50% of Nigerian adults living in rural areas. These are places where access to formal financial institutions or banks are scarce or non-existent.

Thankfully, there is now a new drive for better financial inclusion: Nigeria’s Central Bank has issued licenses for mobile telecommunications companies to start acting as mobile money agents. And, like the M-Pesa mobile money revolution in Kenya, I believe this could be the start of something remarkable in Nigeria. Bloomberg reports that start-up digital bank Kuda opened more accounts in April this year than in the entire first quarter of 2020.

With improving inclusion rates, there is a whole new audience in need of good financial journalism.

Nigeria’s poor are not hard to reach. They range from the petty trader who feels it is unsafe to save, or the cement block-molder who does not know how to apply for a low interest loan. The local farmer who grapples with production and climate change problems, or a local hairdresser who has to juggle cleaning jobs to educate her children.

How do we help a woman like Busayo?

In 2016, my husband met Busayo. She used to clean offices at his place of work. Before they met, she owned a hairdressing salon which she had to close down because of low patronage. Busayo earns $33 every month from the cleaning job, which translates to a little more than a dollar a day.

Busayo is challenged with feeding her four children, sending them to school, transportation to and from working, paying rent and so on.

So every spare moment she has – which is mostly in the evenings over the weekend – Busayo goes from home to home, canvassing to do female children’s hair like my daughter’s, for which she charges 50p each.

Busayo, like many low-income workers of Nigeria, cannot afford a smartphone or complicated financial articles printed in the newspapers. She listens to the news though. She listens through her mobile handset or a lamp she has that doubles as a radio.

This she does in the hopes that some policies that will favour her current financial state may be announced or implemented – like the minimum wage laws recently passed in my country.

Busayo tells me she yearns for knowledge about how to make the future more financially secure for her children. So what can I do to help Busayo and people like her? There are various topics she would benefit from knowing about and understanding. Topics like microfinance, loan accessibility, pension, inclusive banking, and maybe, much later, investment opportunities.

These vital lessons will have to be delivered with engaging storytelling skills, like those I learned at the Reuters Institute.

The task is not simple: these issues will have to be written about or aired in stories that capture the immediate effects of current economic policies, and their impact on individual lives.

To reach Busayo, and similar audiences, these articles will be written in indigenous languages – namely, Pidgin English, Hausa and Yoruba.

And before we can discuss savings and loan accessibility, for example, we will have to explain interest rates. Does Busayo know the official rate of return on most savings accounts is about 4% in Nigeria, while the interest charged on a loan can be as much as 31%?

Through financial education, the population will get a clearer picture about why it is important that they demand accountability from those in power.

Is this a hitch-free idea? Of course not.

As you may have guessed, the shift from writing for the elites to the rural poor in several indigenous languages may not be as easy as expected. But last Autumn I realised this is something I have to do. It is my responsibility as a journalist.

It may require learning new skills – like creating an audio programme that could reach radio listeners like Busayo – but I like learning new things. This is something else I realised during my time in Oxford.

It was my first experience of living outside of Africa – ever my first time outside of Nigeria. I realised quickly that in Oxford one needs a bicycle to move around. Meera Selva, the director of the fellowship, graciously loaned me a spare bike. With the help of my Austrian co-fellow Philipp Wilhelmer, support from my host-family, and plenty of practice I was able to ride a bike within three days.

Learning is a part of what we do best as journalists. Dexterity and persistence are also qualities this profession has bestowed on us.

Above all, my time at the Reuters Institute in Oxford University has taught me that happiness is found in dealing with real problems.

I do realise that additional personal finance reporting is not enough to solve the deep-rooted poverty issues in my country. But it could start discussions that would inform better policy representation.

So even if I have to take my newly learned bicycle-riding skills to the nooks and crannies of Nigeria’s rural poor areas to share the gospel of financial literacy, I believe it will pay off.

I have a video of myself attempting to ride a bike for the first time in Oxford. It will serve as a reminder that trying new things can be scary, but fear is vital for activating the senses against risks and dangers. These are tools I found necessary for thriving as a financial journalist in Nigeria.