In this piece

Forgotten lives: Unpacking the crisis of missing people coverage in UK media

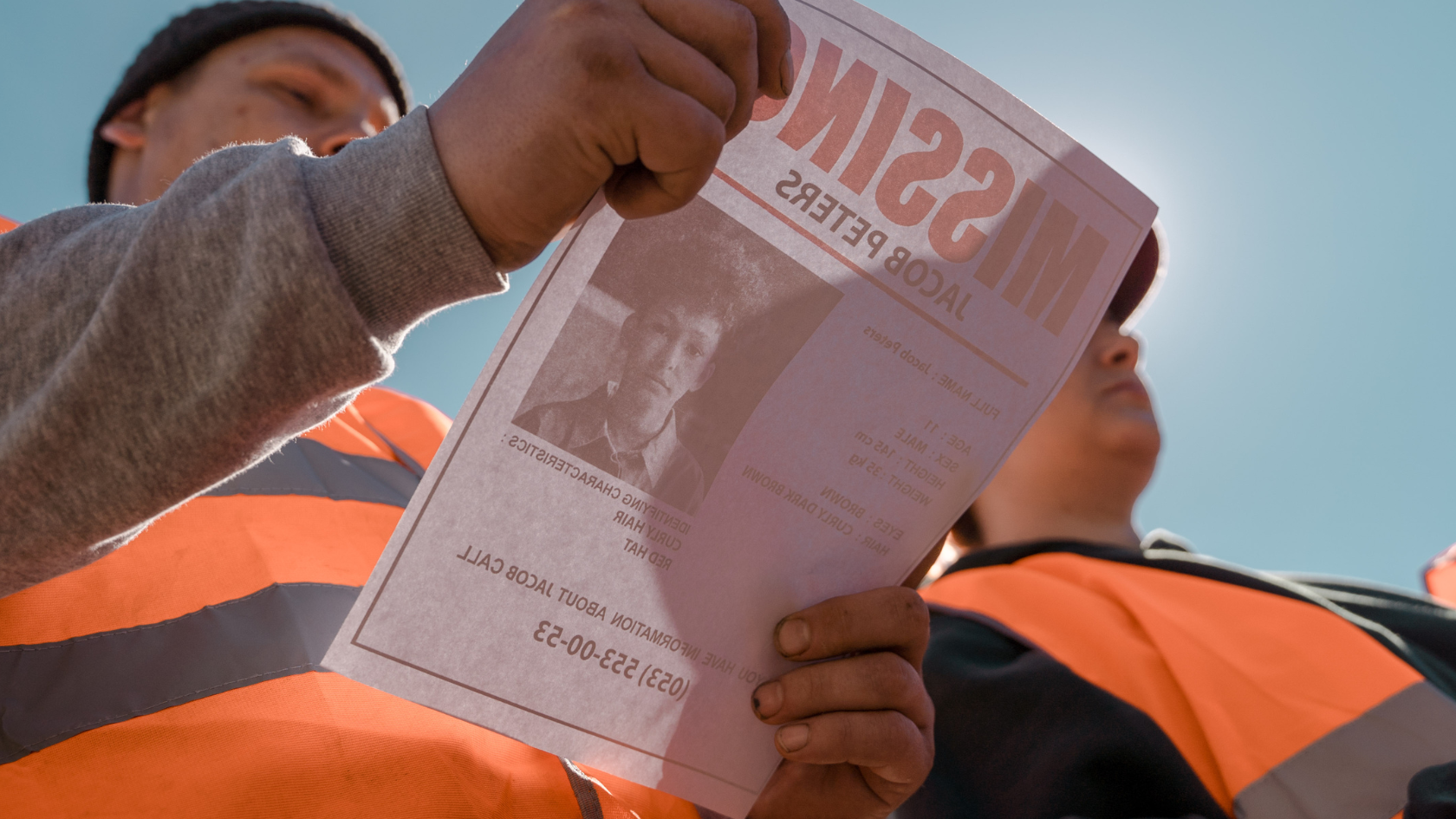

Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff reveals the findings of her six-month investigation into British press coverage of missing people. (Image: Canva stock)

In this piece

What does data show? | It's not all bad | Eight strategies for improving coverage | Get in touchThe issue of missing people in the UK is vast, yet often misunderstood. With over 170,000 people reported missing every year – amounting to one person every 90 seconds – the scale of this crisis is staggering. However, the narrative surrounding these cases is skewed, heavily influenced by media biases that favour certain demographics over others and outdated practices that put profit and page clicks over people.

We can all recall media coverage of missing people: Madeleine McCann, Nicola Bulley, Suzy Lamplaugh are just some of the missing white women who have dominated front pages in our lifetime. But the image that we, the British press, have painted of missing people does not come close to reflecting the reality of missing people as seen in data.

What does data show?

A report by the charity Missing People and research organisation Listen Up found that, despite making up just 4% of the population, around 14% of people reported to the police as missing are Black. They also found Black adults and children are also the most likely to remain missing for over 48 hours and, separately, for over seven days.

“I was really struck by the fact that every single data point showed over-representation for missing Black people,” said Jane Hunter, Head of Research and Impact at Missing People.

The disparity in reporting is not necessarily a reflection of public interest but rather a consequence of deep-rooted prejudices within newsrooms: not just around race, but around occupation, disability, class, gender and other marginalisations. Complex cases involving marginalised individuals with histories of substance abuse or repeated disappearances are frequently overlooked, as they don't fit the "ideal" victim profile that attracts public attention.

“There is something called the news hierarchy. So they look for the idea of the victim through the vector of somebody who’s innocent, somebody is really good, and something bad has happened… because that immediately gets attention. We don’t like that. It’s good versus evil. It’s really simple,” said Professor Karen Shalev, leader of the Missing Persons Research Group at the University of Portsmouth. This selective reporting not only skews public perception but also impacts the allocation of resources and attention from law enforcement.

It's not all bad

While there have been standout examples of responsible journalism, such as podcasts She Has a Name and Your Own Backyard, and Columbia Journalism’s Are You Pressworthy feature, the media's overall approach to missing persons cases has struggled due to a fractured relationship with police, dwindling resources, and outdated editorial decision making.

To better understand the question of how we can do a better job reporting on this issue, I spent six months at the Reuters Institute reviewing the latest research and interviewing journalists, academics, activists, law enforcement, and the friends and family of missing people and developing newsroom strategies for improving coverage.

Alongside the recently published news media guidelines by Missing People, I hope these will be used, interrogated and reflected on by the industry moving forward.

Eight strategies for improving coverage

1. Respect privacy and sensitivity. Everyone has the right to be forgotten. It can be hard for journalists to get stories over the line without families and friends willing to give interviews, but approaches during times of crisis should be considerate.

2. Be more judicious with coverage. Is this story in service of the public and the missing, or is it sensationalised? Not all elements of a missing case can, or should, make the news. Be intentional. Keep in mind that more police resources may be given to investigating crimes when you cover them.

3. Engage with complex stories. Many editors are wary of stories where there’s a history of substance abuse, or where the person has gone missing before. They prefer stories where the disappearance is ‘unusual’ and where there is suspected foul play. But ‘simple’ stories aren’t always what the public want or need.

4. Expand our understanding of victimhood. There remains a refusal to plainly acknowledge racism across British newsrooms, but Missing White Woman Syndrome – the disproportionate coverage of young, white, middle class, often good-looking women, and girls – undeniably exists in the UK. This is why key stories continue to be overlooked.

5. Collect data. Actively striving towards equitable coverage involves taking stock of the types of stories and individuals we are prone to cover excessively. There has never been any type of data collection that attempts to quantify how the British news media tackles missing person cases.

6. Highlight support available to missing people and their loved ones. The charity Missing People is a great resource and should be used similarly to the way Samaritans is for suicide reporting. The Missing People resources are available online here.

7. Diversify our newsrooms. Many of the journalists working hard to tell missing Black people’s stories are black themselves. Initiatives to improve race and ethnicity representation have been losing steam since 2023, and are lagging behind efforts to reduce gender disparities within the media. Diverse staff reporting from diverse communities means fewer stories will be missed.

8. Make space for specialist roles. The relationship between the public, the media and the police is fundamentally broken. Engaging with families in a respectful, responsible, and effective way is a steep learning curve. Both issues can be countered when general reporters are able to focus on the missing, and can forge better relationships between stakeholders while championing impartiality.

Get in touch

For a more in-depth look at the crisis, our coverage, and strategies for changing the status quo, please see the full PDF of the project below.

In the meantime, I would love to speak to more reporters and news editors about their experiences, as well as people who have gone missing and their friends and family about their experiences with media representation.

Get in touch if you want to collaborate, or if you have a missing person’s story that you feel has been underreported by emailing me here.

This project and fellowship have been made possible by the support of the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time