In this piece

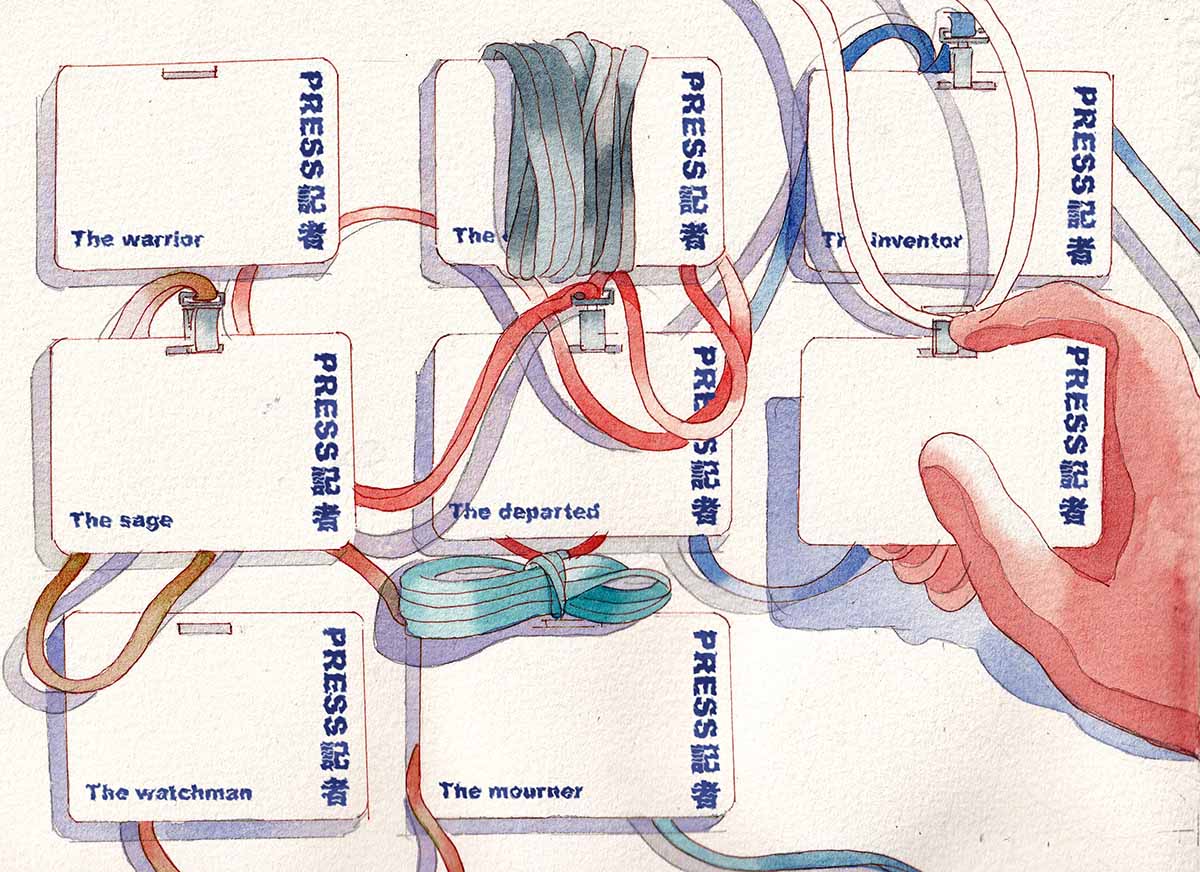

The fate of Hong Kong's journalists under China's rule: seven stories of broken dreams, perseverance and hope

The fate of Hong Kong journalists. Illustration: Running Swan

In this piece

The Exile | The Inventor | The Sage | The Mourner | The Watchman | The Departed | The Warrior | ConclusionHong Kong was handed over from British to Chinese rule in July 1997. For the next six years, the media in Hong Kong continued to thrive under an “open door policy” with Mainland China.

By 2003, many journalists say that the honeymoon was over and the “real handover” had begun.

The National Security (Legislative Provisions) Bill 2003 proposed amending several laws to make it possible to prosecute against Hong Kong Basic Law Article 23, which states that Hong Kong “shall enact laws on its own to prohibit any act of treason, secession, sedition, subversion against the Central People's Government, or theft of state secrets, to prohibit foreign political organisations or bodies from conducting political activities in the Region, and to prohibit political organisations or bodies of the Region from establishing ties with foreign political organisations or bodies."

That bill was shelved temporarily after huge protests by half a million people in Hong Kong – the largest demonstration since the handover and also the largest protest ever directed against the Hong Kong government itself.

The law was the embodiment of the difference between Mainland China and Hong Kong societies: they are as alike as iOS and Android in the ways they operate. Since 2003, the two operating systems have been at odds again and again – always marching towards a flashpoint over Article 23.

In 2012, government offices were besieged for 10 days by protestors against a school curriculum proposed by the Education Bureau of Hong Kong. The 2014 Hong Kong protests over proposed reforms to the Hong Kong electoral system – also known as the Umbrella Movement – lasted almost three months. In 2019, more than a million Hong Kongers again protested, this time against an amendment to the Fugitive Offenders Ordinance that would give China power to extradite political dissidents from Hong Kong to face trials on the Mainland.

To suppress these protests, the National Security Law (NSL) was passed on 30 June 2020. The law allows authorities to surveil, detain, and search persons suspected under its provisions and requires publishers, hosting services, and internet service providers to block, remove, or restrict content that it deems to be inciting secession, subversion, terrorism, and collusion with foreign organisations. Any verbal speech to this effect is considered a crime, too.

This is a problem for Hong Kong journalists, most of whom believe in the principles and values of a free press – providing audiences with accurate information, even when it is not to the liking of those in power.

Carrie Lam, the Hong Kong Chief Executive at the time, made a speech at a United Nations Human Right Council meeting on the same day the National Security Law became operational in Hong Kong. She said the law “will only target an extremely small minority of people who have breached the law” and that “the life and property, basic rights and freedoms of the overwhelming majority of Hong Kong residents will be protected”.

It appears the “extremely small minority” includes journalists. Since the passing of the law, Apple Daily and Stand News have been closed down, their editors have been arrested, and their assets frozen. The city’s public broadcaster, Radio Television Hong Kong (RTHK), has been turned into a government mouthpiece. Hundreds of journalists have lost their jobs.

According to a survey of 500 journalists by the Hong Kong Journalists Association a month after the NSL passed, 87% of respondents felt it would seriously affect freedom of the press in Hong Kong. Respondents mentioned being worried about reporting sensitive topics like Hong Kong independence and Uighur issues, as well as threats to their personal safety.

A 2021 survey by the Foreign Correspondents’ Club Hong Kong found over 80% of journalists surveyed said the new law had worsened their working environment. Almost half of respondents were considering or had already made plans to leave the city due to concerns for press freedoms.

These numbers are worrisome but they do not tell the full story or give a sense of the real-life impact of NSL.

That is why, during my stay at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, I spent my time interviewing Hong Kong journalists. Here, I have gathered seven archetypal stories of the consequences of NSL on journalists’ lives.

For security reasons, all names (bar the first) and some identifying details have been altered.

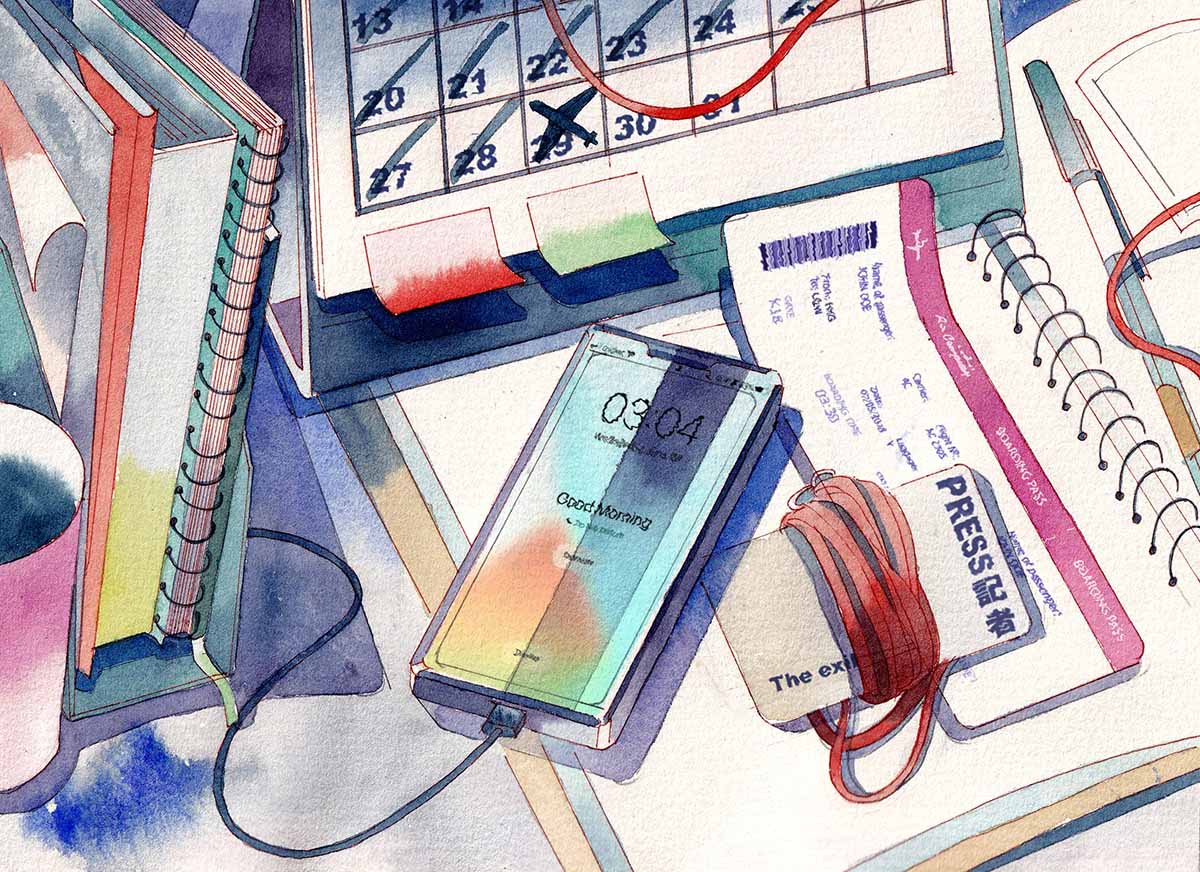

The Exile

Alvin Wong had three days to pack up his life and leave Hong Kong.

“Orders came down from Beijing's top leadership to eradicate Apple Daily,” he told me. “We had set up a leadership contingency plan as soon as the National Security Law was passed. There were nine people on the list – all senior and middle editorial management – who were meant to take the lead when things got rough.

“I was number eight on that list. All seven journalists ahead of me had been arrested. I had no choice but to go.”

Alvin was the Deputy Editor-in-Chief at Apple Daily. He left Hong Kong and applied for a BNO visa to stay in the United Kingdom. The whole process of leaving, he said, made him feel like a refugee escaping.

“I didn’t have time to get all my personal affairs in order,” he said. “I left authorization rights to my family members to help me handle it.”

For Alvin, this whole episode seems like someone else’s life: he can’t quite believe that things escalated to the point of having to flee his own homeland.

Like many in Hong Kong, he knew the situation was becoming untenable, but he never imagined it would impact him so personally. He said there were three main incidents that led him to the conclusion that he should leave.

The first one was what happened to publisher Jimmy Lai and the handling of the case brought against him. Alvin saw this as proof that he and his colleagues would have no recourse to justice in a fair legal system if their number was called.

Secondly, it was hearing information from insiders that it was not Apple Daily that was being targeted, but all who worked there. “Even journalists working on something as innocuous as the travel beat heard from sources that they were not safe from prosecution.”

Finally, when Apple Daily’s senior political journalist resigned, he took this as a cue that big trouble was coming. “All of these incidents helped me understand that we were in danger.”

“If there was a 1% chance that Apple Daily might have survived, I would have stayed,” he told me. “But ultimately I didn’t have the power to change our fate: I had to do my best to reduce the fallout and the trauma that would be caused by our closure – removing myself as a target and encouraging others to do the same.”

“Saving Apple Daily" changed in Alvin’s mind from saving the outlet to keeping as many staff safe from harm as possible. “If we had to die,” he said, “let us die on our own terms, and not by a sword at our necks.” Laying off employees would be a way to keep them safe, and Alvin was very eager to keep editor-in-chief Ryan Law Wai-kwong from Jimmy’s fate: “His situation was very dangerous: we didn’t want him to suffer.”

But a lot of staff wanted to believe they weren’t important enough to be targets for arrest, or felt it was their duty to continue the fight. Top management was not going to be able to offer legal support to everyone, and inside sources kept confirming: it’s not just the outlet’s licence and owners that were at risk – it was even employees at a middle management level who had been marked for legal sanctioning. Some might even be called upon to testify against their bosses.

On the last day of May 2021, Alvin resigned, packed his bags, and flew to London. He didn’t tell anyone.

Two weeks after landing, he got a call from the wife of Ryan Law: 500 police had raided the Apple Daily office and arrested several top managers. Alvin and Ryan were not close personal friends, but at work they were great colleagues who relied on each other – so much so that Ryan had told his wife to call Alvin in the event of an emergency.

“It filled me with guilt not to be there,” he told me. I couldn’t sleep that night: I was passing messages between my former colleagues and his wife. They were suffering so much.”

Alvin’s colleagues were charged with colluding with foreign governments and all were denied bail. The last issue of Apple Daily was published on 23 June 2021.

Alvin said he battled depression for many months after the news. “If Apple Daily can be made to disappear in this way, it can happen to anyone,” he told me. “They can ban any dissenting media they want to. And, when the day comes, the government can appoint their representatives to run the media. Journalists will have no way to write from the heart.”

Alvin thought he had left journalism behind in Hong Kong, but he said he’s found that many new immigrants are looking for Hong Kong-style news media outlets in the UK. He hopes to continue serving Hong Kong society in some small way by catering to their needs.

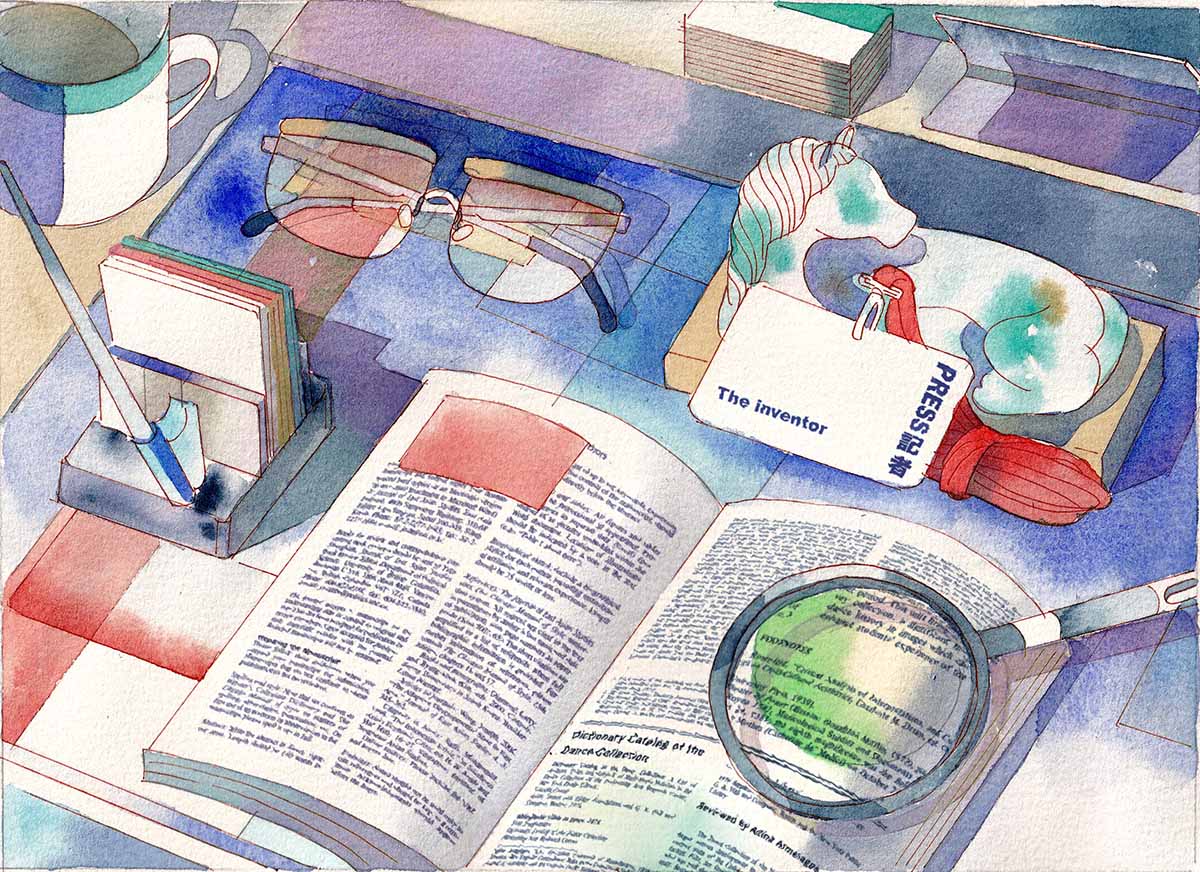

The Inventor

The only way to keep reporting on Hong Kong accurately is to leave Hong Kong and leverage technology to bring together audiences from a distance. So says Man.

“When the government issued the National Security Law as a weapon against us, it meant that they were on the offensive and holding us to account for everything,” he told me. “It’s hard for a journalist to handle this level of threat. Leaving Hong Kong is the only way we can take it.”

In 1997, when Hong Kong was handed over from British rule to Chinese rule, Man was a cub reporter and decided to leave journalism just before the handover. Despite assurances to the contrary, he didn’t believe the Community Party would allow Hong Kong or its media to enjoy the same degree of autonomy.

His decision lasted all of three months – the lure of journalism was too strong for him. Once he was back in the trade, Man stayed for over 25 years. It was, he now realises, “a honeymoon period” – and one the Hong Kong media took full benefit of.

The goodwill back then was palpable, he said, and official sources in China told him the “open door policy” would continue. Those favourable rumours changed when Xi became the top leader in 2012.

His Mainland sources stopped speaking about open doors, and began talking about protecting national security and stories of unity – not dissent. He recalls how a prominent media owner in Hong Kong sold his press holdings to a Mainland investor in those early Xi years. The sale followed a summoning of the owner to the Liaison Office in Hong Kong where he was forcefully rebuked over unfavourable coverage. An example, Man said, of the invisible hand of the Chinese government.

For Man, and many like him, the passing of National Security Law was the real handover of Hong Kong they’d been waiting for since 1997. “In 1997, no one worried about their personal safety while working as a journalist. Now it is different. There is no room for independent media outlets in the New Hong Kong.”

If the new Chief Executive upholds a promise to create new “local legislation” that meets Article 23, there will be a whole new raft of laws for prosecuting journalists. That will be Man’s signal to leave.

But he will wait until the bitter end, plotting and planning how to continue. “Hong Kong was the place I grew up and gained success from the good times. It’s time for me to give back to our society. I want to stay a while and help young journalists.”

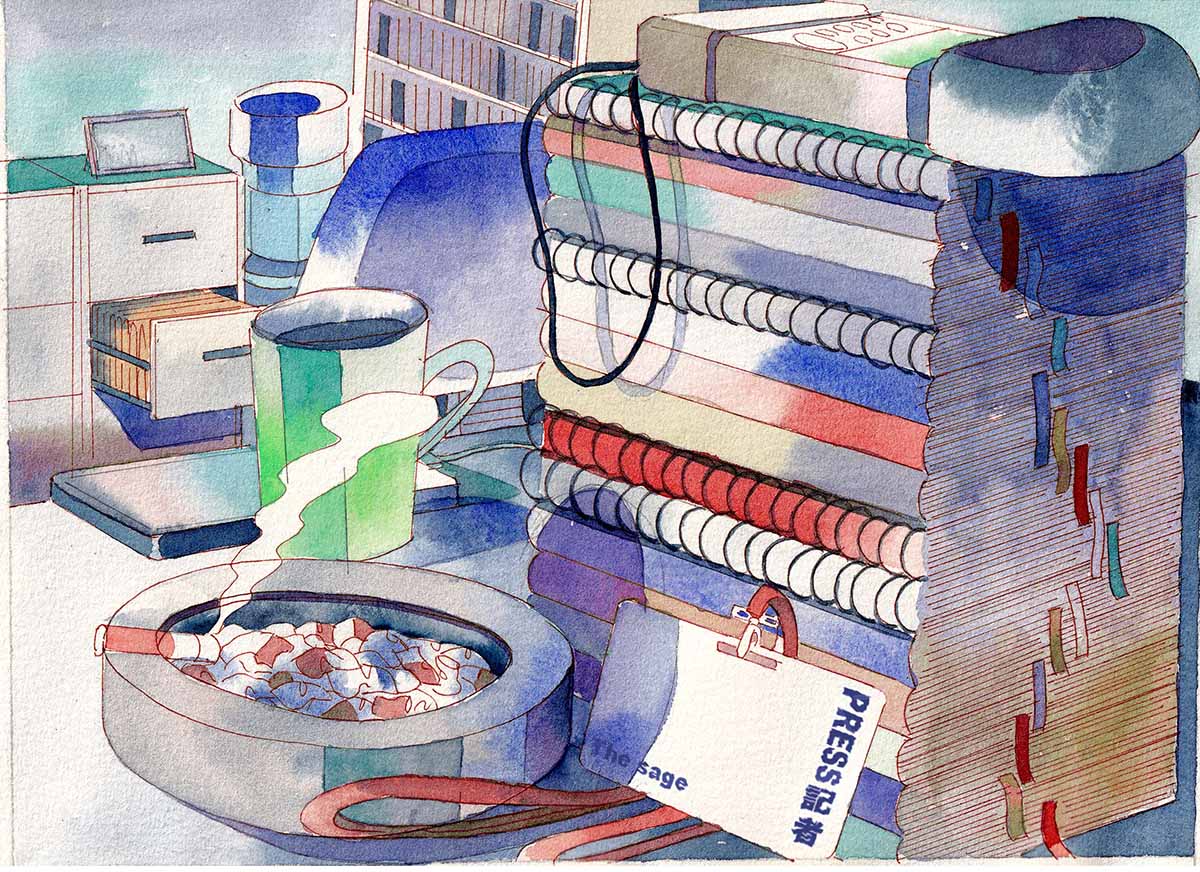

The Sage

Sum has spent 30 years of his life working in journalism. Now he hopes to inspire his journalism students to stay with him, recording up until the last moment of Hong Kong press freedom.

“If journalism is waiting to be executed, I want to be a witness with my students,” he said.

Sum was lucky to join the industry in a golden age when the media in Hong Kong was full of resources and credibility, he told me. In his day, he covered the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. He resigned in 2004 because of what he felt was censorship by top editorial management at the TV station he worked for.

“Back then, I felt I would be able to return to the frontline at any time I wanted. Now it is a totally different situation.”

He missed some remarkable stories between 2012 and 2017, so he returned to journalism, no longer satisfied to watch from the sidelines. In 2019, he worked as a fixer for overseas news teams covering the protest.

He also worked for the public broadcaster Radio Television Hong Kong (RTHK) as a documentary producer, working on projects about police abuse of power and immigration officers treating refugees poorly. “All the news topics I worked on are too sensitive for the newsroom now, and banned from mainstream media because of the National Security Law,” he said. “But when society is full of anger, people need journalists to tell the truth.”

A radical shift in policy at RTHK under the leadership of Patrick Lee, who took office in March 2021, led to sweeping editorial reform. The budget for Sum’s investigative documentary team was cut, and he and five colleagues were let go.

Now Sum divides his days between running a bookshop, and being a part-time teacher at a local university. “At my age, I want meaningful work. Being a journalist is meaningful for me.”

Even for a seasoned veteran of the trade like Sum, the collapse of Apple Daily was distressing. He was working from their office on a documentary during its final days, and recalls asking the acting editor-in-chief Lam Man-chung to take a cigarette break with him. Standing outside, Sum shared his concerns about Lam’s situation. He believed that Lam was on the arrest list.

Lam inhaled deeply and said he didn’t have time to worry about that. Finishing their final edition was his only priority. Lam was the eighth person arrested from Apple Daily. “He has real backbone,” Sum told me.

The Mourner

Last year, Choi’s former colleagues asked her to sign a birthday card for their old boss at Apple Daily, Ryan Law Wai-kwong. The former editor-in-chief remains in detention in Hong Kong, where he is awaiting trial on charges of sedition.

“I picked up the pen and stared at the words ‘Happy Birthday’ on that card. All I could think was: ‘What’s happy about it?’ What words could I possibly write to my editor-in-chief on the occasion of his birthday in prison?” Frozen by despondency, Choi found she couldn’t sign it.

This is one example of the many ways depression pervades Choi’s life since leaving her dream job, beloved colleagues, and the place where she was born.

Her career in journalism began in 2014: the same year as the Umbrella Movement. When she joined Apple Daily as a fresh J-school graduate, she thought she was embarking on the career of a lifetime. The outlet was a utopia for journalists like her. “Apple Daily gave complete support and resources to journalists,” she said. “My boss showed full trust in my work; I had room and freedom to write what I wanted.”

Choi enjoyed every moment of the five years she spent at Apple Daily, but reporting on the 2019 anti-government movement was a real highlight. She took on a frontline reporting role, and many in Hong Kong watched her live streams or looked out for her challenging questions at press conferences. She made a name for herself with her passion and hard work.

Everything changed when the Chinese government imposed National Security Law and Choi received a strange call. “One of my legal sources wanted to talk about the new law. Very calmly, he told me to think carefully about my future – whether I would stay or leave – not just my job, but Hong Kong. I was in shock hearing this warning,” she said. She’d never before considered her work to be dangerous.

Choi discussed the warning with her family and they asked her to apply for a working holiday visa to the United Kingdom. She made them a promise: when the visa was approved, she would resign. But she was extremely conflicted about going. “I was due to get a promotion that year. I didn’t want to abandon all I had worked for over some vague new law. It seemed unfair to me.”

On 17 June 2021, Choi watched on in terror as six of her bosses were arrested and led away by police. Other officers searched through their newsroom for evidence. Everything was turned upside-down in an instant: her once happy workplace was now gripped by uncertainty and fear.

It felt like the worst timing in the world, but she knew what she had discussed with her family and she would need to leave as soon as possible. She walked to her line manager’s desk that same day – with her head down and tears falling – and handed over a resignation letter. “I don’t remember my exact words: I think I said that I really didn’t want to go but that I was too scared to stay.”

Retelling this story nearly a year later, Choi cries all over again. “I felt sad, and I blamed myself for being weak– too cowardly to stand with my colleagues until the last moment.”

On 23 June 2021, thousands of Hong Kongers lined the streets outside Apple Daily’s office in the heavy rain. They wanted to ensure the paper could publish its final edition without police interference.

Choi’s family forbade her from joining that crowd, but watching the live-stream she couldn’t control herself: she ran from home to the bus station. Her phone rang, and it was her family begging her to return. She sat sheltering from the rain for a long time as the buses came and went, debating what she should do. She didn’t want to worry her family anymore than she already had. And, anyway, she feared she would be seen as intruding on her colleagues who had stayed till the end. With a heavy heart, she turned and returned home.

Today, she says, this is her greatest regret. “I will never forget that I behaved like a deserter: this will be a lifelong trauma for me.”

At the airport, days later, Choi was on tenterhooks: one of Apple Daily’s top managers was arrested while preparing to board his plane. She asked her boyfriend, who was flying out on the same day on a different flight, to stay near her gate and keep his phone at the ready. “In case I was arrested, he could film the process and call my family.” She didn’t stop worrying until her plane left the ground.

Choi has settled in London now, with a stable part-time job. But, without fail, as evening draws in, so do her memories of her former colleagues and her regrets. She says she will live with a sense of pity for the rest of life.

The Watchman

Snow was studying drama at university when she packed in her acting dreams and became a court reporter in 2019. She wanted to ensure an accurate account of the 2019 protests was being recorded.

“The protests broke out just outside my college,” she said. “I couldn’t just pretend nothing happened and carry on.”

As more and more young protestors were arrested and sent to court, Snow noticed that many of them were top students: “A Yale University student and a PhD graduate were among them – the public needed to know their stories. Why did they join the protests? What were they asking for?”

She also wanted to record how the law was used to send protestors to jail. “I wanted to deliver their messages to the public, and help the public reflect on the meaning of the protests.”

As COVID-19 arrived and the protests died out, Snow knew instinctively that the battle had moved from the streets to the courtroom. Who recorded these proceedings would matter – and so would ensuring that reports didn’t only cover the big guys and politicians.

It’s not a task she relishes: “For me, being a court journalist is the most boring job of all. If the anti-government protests had not happened, I would absolutely not have made this choice.”

Now, every working day, Snow travels between the different courts in Hong Kong to stand as a sentinel or record keeping.

And she’s found her work is not just important to the public, but to legal professionals, too – even they are still grappling with how the National Security Law is applied.

Because the new regulation was written under the Mainland China legal system instead of the Hong Kong common law system, it’s been difficult for many to understand the letter of the law. Reading the verdicts she records in her court reports has helped both professionals and the public to understand how to protect themselves and their clients from future violations.

Although she has only been working this beat for a year, she has already had some unforgettable experiences like hearing the verdict levelled in the case brought against a 15-year-old child.

She was the only journalist in court that day. As she entered the building, she noticed a group of school boys crying and hugging their friend who planned to plead guilty and face a 10-year prison term. The farewell was painful to watch, but important to record. She felt glad that she was here.

Being a court reporter, she says, is probably relatively safer than any other kind of reporter in Hong Kong right now. After all, the proceedings are a matter of public record and the facts speak for themselves. But she still feels powerless at times: like when a judge bans reporting of certain case details.

“I don’t have a crystal ball to read the future with; I don’t know how long I can stay in this position or when I will lose all room for reporting. But people have the right to accurate court reporting. If one day I am arrested because of my job, I will still be proud of what I did as a Hong Kong journalist. No regrets.”

The Departed

Young Cheung Shan has given up on journalism. Once inspired by the value of the profession during the Umbrella Movement in 2014, he says all that inspiration dried up when the National Security Law was passed.

“The National Security Law feels like a sword on the neck of journalists. They’re working with their hands tied now and cannot report what they see,” he told me. “If journalists can only stick to the official version of events, I don’t see the value of being a journalist.”

It made more sense to him to leave the profession – with his good memories intact – before journalism in Hong Kong became part of a propaganda machine.

“I wanted to use my journalistic privilege to be a witness to the change happening in Hong Kong after the Umbrella Movement,” he said. That motivation kept Cheung Shan in the industry for the next five years. When the 2019 protests began, he signed up to cover the frontline of the protests, which lasted six months.

Cheung Shan’s eyes still shine when he recalls what he witnessed during those protests. Speaking to the protestors and capturing their voices was an honour, he said. “I was the lucky one. If I’d left the industry too soon, I wouldn’t have had the opportunity to hear first-hand the true feelings of the public.”

But he paid the price for the privilege when he was hit by a water cannon carrying chemical-laced “blue water and tear gas” which left his whole body in pain. The incident left him shaken and fearful of any approaching government vehicles, but he was determined to maintain his position on the frontline.

The environment in his own newsroom was far less resolute: Cheung Shan witnessed his editors self-censoring, and backing away from journalism principles. It made him feel sick and depressed. “There were several topics and issues that we needed to follow up on, but management banned all coverage related to the resistance. There was no reason for me to stay in the industry; I didn’t want to be a government mouthpiece.”

Like most journalists in Hong Kong, Cheung Shan now divides his career into before 30 June 2020 and after 30 June 2020, when National Security Law was imposed in Hong Kong. Watching what happened to Apple Daily and Stand News would destroy any last hope he held. “If an outlet as strong as Apple Daily was forced to shut down, I don’t think any outlet has the power to resist government control,” he said. “It was like Black Hawk Down: a symbol of the destruction of press freedom.”

The Warrior

Era took courage from other journalists who stood firm until their outlets were forced to close down. She is willing to keep working until her arrest.

“Under the shadow of National Security Law, doing journalism in Hong Kong is more dangerous than before. But we are the last stand: we cannot be weakened by fear,” she told me. “If journalists need to pay for telling the truth, that is a price I am willing to pay. At least my mind will be at peace.”

Era was a student at the time of the Umbrella Revolution. She stayed in the occupied area, talking to many protestors and documenting for herself what was happening. The experience inspired her to pursue a job as a reporter.

In 2019, when the second protest wave began, she was abroad. She was straining to return – knowing she was missing an important moment in history. As soon as she could, she returned to Hong Kong to start work as a journalist.

Unfortunately, the National Security Law was coming.

Initially, Era was very worried about the new law – especially after seeing what happened to Apple Daily. She spoke to her boss about how risky it would be to keep working and was told: “I don’t think our names are on the list yet”. It wasn’t exactly the reassurance she was hoping for.

Era found herself worrying that the unclear definition of the new law and constantly shifting red lines could affect her work. Her inspiration to continue came from watching other journalists stand firm until the end. She learnt from them what it looked like to be brave.

Her technique now is to balance her fears against the mission of her work. Three years in prison, she said, seems like a price worth paying for telling the truth. The work may be harder under the current conditions, but she still feels she knows how to remain relatively safe and work between the lines.

“Hong Kong is not yet like any other city in China. I still have room to do my work, and I want to keep recording Hong Kong history as much as I can,” she said.

“The only way to guarantee I am safe is to stay silent. But I can’t be happy that way.”

Conclusion

A common point in all seven stories told here is the significance of the collapse of Apple Daily. It was more than the end of an outlet for us – it was the end of press freedom. That is why I felt moved to capture this snapshot of Hong Kong journalism before and after the closure, not through numbers or dry dates or earnest analysis but through the personal stories of those most impacted.

On the wall of the Newseum in Washington D.C. were the words: “We pay tribute to the reporter who is willing to stand when others run, who will press on with questions when others have been cowed into silence.” This is the journalist I want to be, and this is the kind of journalist I met in interviews for this paper.

For my interviewees and I, journalism is more than just a job that can be done anywhere. It is a service to the society we were raised in. That’s why we can’t simply pick up and move somewhere safer – not without heartache.

Where are they now? Mr. Exile works on a news platform in the UK that aims to keep reporting and serving Hong Kongers. Miss Mourner is a freelance journalist working for various media outlets set up by the Hong Kong diaspora. Mr. Departed has left journalism but he still works in a field related to media, and he does his best to serve journalists and the public in his new position. My other interviewees are all still in Hong Kong at the time of this writing.

I know this paper won’t change the situation in Hong Kong, but it can serve as a reference and way to ensure we do not forget what is gone.

The story I most closely identify with is Sum, the Sage who left frontline reporting duty and missed out on reporting important moments in Hong Kong history. In 2012, when the Civil Alliance Against National Education began protesting and during the anti-government movement of 2019, I was stationed in Beijing as a correspondent. I missed these historical moments in my city. In a sense, this paper was a tonic for that regret.

Perseverance, I believe, does not only happen. “We not only persevere when seeing the hope, but creating the hope.” This is another popular slogan in Hong Kong in 2019. Journalists in Hong Kong use our lives to set up an example of how perseverance can create hope. We want to set an example for the next generation and to encourage our young journalists that they are not alone.

I want to thank all Hong Kong journalists who have fought for our principles and beliefs until the very last moment. It is not hope that sustains our perseverance, but perseverance that sustains our hope.

Add oil, Hong Kong!