Reporting extreme weather – a case study of the 2022 Indian heatwave

Cover of the report on the media coverage of the Indian heatwaves.

In 2023 heat records were broken all around the world - from Canada, the Mediterranean to South Asia. The World Meteorological Organisation says last year is set to be the hottest on record, leaving a ‘trail of devastation and despair’.

India is no stranger to heat records. The Indian Meteorological Department said February 2023 was the hottest since 1901. This followed the 2022 heatwave which was exceptional for its record temperatures, its early onset, its unusually long duration and the large area that was affected.

According to the science organization World Weather Attribution (WWA), the heatwave was made 30 times more likely due to climate change.

A new report looks at how the Indian media covered the 2022 heatwave. It includes a wide range of English-language outlets, videos, and articles in Hindi, Marathi and Telugu – all languages spoken by far more Indians than English as their first language.

A team of researchers, including three from India, examined around 150 articles and 10 videos.

The WWA says that journalists across the world makes three common mistakes, namely:

- ignoring climate change as a cause of the event

- attributing the event to climate change without providing any evidence for that claim

- attributing an extreme weather event to climate change as the sole cause.

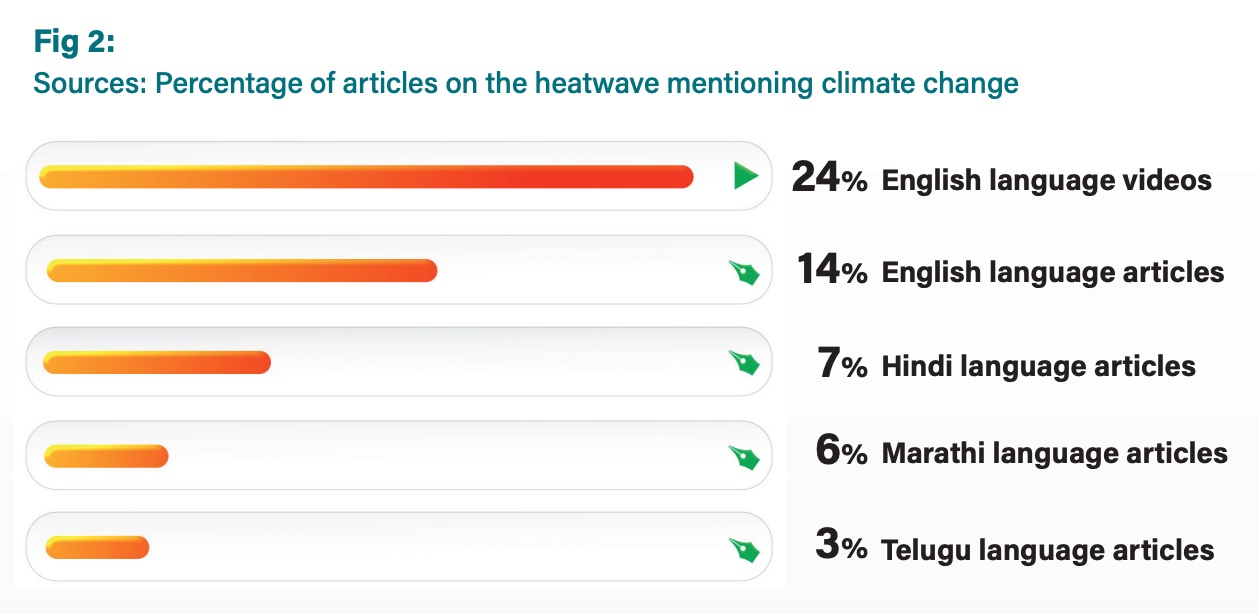

So we first looked at the extent to which climate change was mentioned by journalists covering the heatwave. This was particularly relevant as leading climate scientist, Dr Friederike Otto, recently told a Reuters Institute seminar that ‘every heatwave is made more likely or more intense by climate change’.

The percentages of articles covering the heatwave and mentioning climate change ranged between 14% and 3% (see Figure 2 from Report) – a low figure, which is common across coverage in other countries too. A strong case can be made that the link to climate change could have been more emphasised in some of the media coverage, particularly in the early days of the heatwave in March and April.

On a positive note, a high percentage of English-language articles accurately reported the link: more than 70% of the articles either presented climate change as making the 2022 heatwave more intense or more frequent, or used a variant of a generic trend statement such as ‘this heatwave is the sort of event which (scientists say) could become more frequent and/or intense in the future’.

In contrast, in the Hindi-language sample, a large portion were less accurate – they used a direct binary causation statement (such as ‘the heatwave was caused by/due to climate change’) to describe the link (67%), a much higher figure than for our English-language sample (19%).

Other positive results concluded that:

- Two Extreme Event Attribution studies published by the UK Met Office and the WWA released in May 2022, were widely quoted in both the English-language and the Hindi-language news sites (18% and 26% respectively).

- A very high percentage of the quotes about the links between the heatwave and climate change came from Indian scientists or meteorologists both in our English and other-language samples. (See Figure 5 from report) This contrasts with previous studies which suggested that politicians and NGOs were widely quoted, often without mentioning the science.

- In contrast to the images used by some Western media in the coverage of heatwaves in India and elsewhere, there was no usage of images of people enjoying the heat. On the contrary, most of the images accompanying the texts were of ordinary people seeking relief from the sun.

- Journalists regularly covered three aspects that affect the impact of the heatwave on ordinary people, namely emergency responses, disaster planning, and vulnerabilities.

However, in general, reporters from non-English language sites did show some inaccuracies, often due to language constraints and lack of resources. Like others, we recommend more training programmes for general reporters working in languages other than English and for the regional press.

Guidelines should be made available in more languages on how to report accurately on heatwaves, and encouraging journalists to give sufficient weight to all aspects of the heatwave story.