As Putin’s troops attack Donbas, local journalists keep reporting on life and death

A woman reacts near her critically wounded dog during a Russian strike in Kostiantynivka. REUTERS/Gleb Garanich

As three Russian rockets flew over her house in February, Mariia Davydenko realised she would need to evacuate her team. She lived in the Donbas region, around 50 kilometres from Ukraine’s eastern border with Russia and she was head of news at independent news outlet Vchasno, whose office was also based on the frontline. “It was scary and a big shock,” she says.

The Donbas region in Eastern Ukraine has been at the centre of a separatist conflict between pro-Russian forces and the Ukrainian government since 2014. Armed rebels declared “People’s Republics” in the Donetsk and Luhansk provinces. Vchasno was founded in 2015 and has covered these ongoing conflicts and the attempts to broker peace ever since. An escalation in Russian military activity before the Russian full-scale invasion, however, meant the newsroom could no longer safely operate from the region.

Vchasno’s main audience is located in Donetsk and Luhansk provinces. The outlet has covered significant changes in the past eight years, from corruption to social activism that has brought positive changes in the form of new roads, hospitals and schools.

The impact of Putin’s invasion

Life hasn’t been easy for Vchasno’s journalists after the Russian invasion. Davydenko’s colleague Olha Kyrylova was on the train to Kyiv for media management training when Russian troops crossed the border and she decided to turn back, with her return journey disrupted by an explosion in the city of Dnipro.

“We tried to organise fast and to rebuild our work. We understood that it was important for our audience to stay tuned about the events,” says Kyrylova. “A lot of people read us. They need us for this information, so we keep working for our audience.”

The team was able to continue operations within a week of the full-scale invasion. For two months after, the team worked without a single day off. Then they divided into two teams and started working in shifts. “It was very stressful, so this is a better model for us,” says Davydenko. “It helps to save some emotional space.”

All the members of Vchasno’s seven-strong newsroom are still in Ukraine, but the majority have been forced to leave the Donbas region due to safety concerns, including threats from Pro-Russia militants. In February, two of Vchasno’s male members of staff went to defend Ukraine, says Davydenko, who adds that international partners have provided body armour for her journalists. The team has also tried to provide work for displaced journalists from the Donbas region who are still in Ukraine.

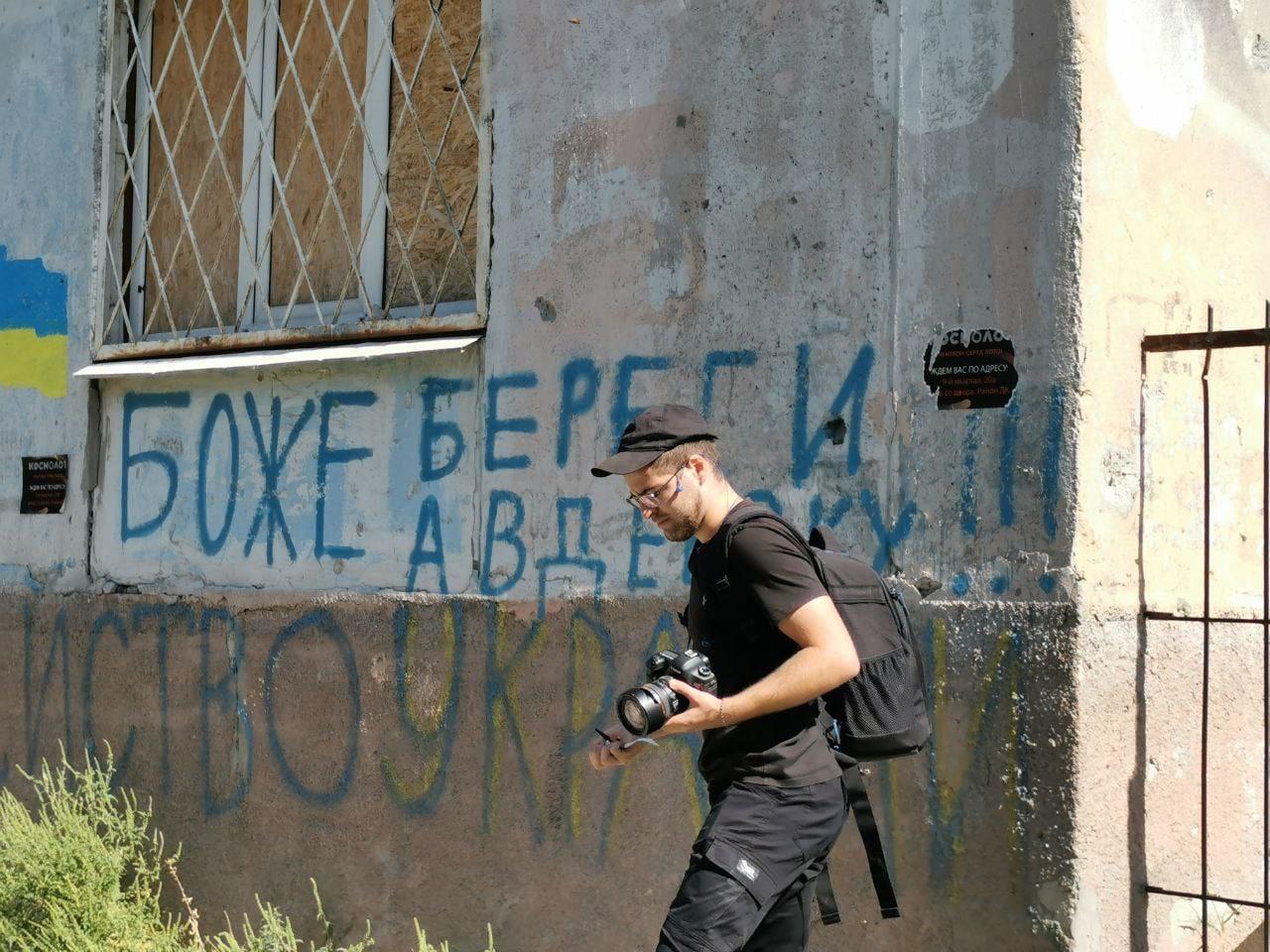

After the first few months, a few journalists have returned to their home region to report and conduct interviews, while the newsroom keeps in close contact with volunteers, activists and civic organisations to keep reporting from a distance.

A magazine halts its plans

Shortly before the full-scale invasion, online magazine Svoi City was preparing to set up a central office in Kramatorsk, in the north of the Donetsk province. As its editors were about to have face-to-face meetings for the first time after years of remote working, their plans were halted.

“When the war started, our main aim was to guarantee the safe evacuation of our journalists and everyone who worked for us,” says managing editor Haiane Avakyan, who speaks to me with the help of a translator.

The first group of Svoi City journalists moved on 24 February, with the final two evacuating Donbas by the end of March. The team was able to resume its reporting just five days after the invasion began, says Avakyan.

Svoi City has two full-time journalists and works with a network of freelance contributors. One of these contributors had to flee Mariupol for Dnipro. Another one has been evacuated to Kyiv.

Ensuring that all journalists who work with Svoi City are accounted for is crucial, says Avakyan: “We decided to invite all the freelancers into the team taking our staff number up to 10. We wanted to keep them safe, give them salaries and make sure they can write stories so everyone knows about the situation.”

Avakyan is originally from Bakhmut, a city to the north of Donetsk and west of Luhansk. She stayed there during its occupation by pro-Russian separatists in 2014 and its subsequent liberation by the Ukrainian army. In February 2022, though, she fled to Lviv. After three months there, she moved to Kyiv. Several members of the Svoi City team were twice displaced. The psychological impact on local journalists who continue to cover Donbas while dealing with safety concerns for themselves and their families is profound.

“It’s very difficult to see our cities being destroyed after being rebuilt and restored in the past eight years,” says Davydenko. “We hear about the death of people we know and the destruction of places we know.”

A traffic surge

From February to March 2020, Vchasno’s website traffic increased by 200%. A dormant Telegram channel relaunched in February grew from 100 subscribers to 7,700 by early April and at the time of this writing stands at 9,048. Svoi City has seen a similar boost on Telegram, with subscribers growing from 400 to 4,000 in the first two weeks of the invasion.

While Vchasno published an English-language version of its website before the full-scale invasion, Davydenko and her colleagues realised in February that they needed to increase their English-language output. “There are Ukrainian outlets with English versions but not a lot of local journalists, so this is important,” says Kyrylova. “We publish news about cities and lives destroyed by Russians, so people can see all the atrocities in the Donbas.”

Domestic audiences are especially interested in ordinary people, says Davydenko. This includes stories of doctors, postal workers, IT specialists and local businesses who are working to “defend the homeland”, such as these local entrepreneurs turned ammunition manufacturers. Reports on internally displaced people and on early trials of “people who have betrayed Ukraine” are also popular. Writing stories about the army has been tough. “Some died at the hands of Russian soldiers, but I’ve had to overcome the emotion and understand that it’s important for us as journalists to tell the stories of these everyday heroes,” Kyrylova says.

Svoi City launched four years ago as a publication focused on the lives of people living in Eastern Ukraine. The magazine is now centred on the lives of ordinary people, with a focus on features-led reporting and not so much on news updates. Its coverage of the soldiers defending Mariupol and the Azovstal steel plant, for example, has focused on their personal relationships and on the love story of a defender who was engaged to be married in July.

“We talk about people and give them hope,” says Avakyan. “The focus is on you and on something you are part of.”

This includes covering ways that readers can safely escape the conflict and sharing safe routes to leave occupied regions. While the team still has many contacts on the ground and works with freelance journalists specialised in military reporting, it is “next to impossible” to get reliable information from the region, says Avakyan. Ukrainian mobile phone operators no longer work in Donbas as they’ve been blocked by Russia, but information can be sourced through Viber and Telegram channels, as well as from foreign news reports and journalists.

“We can use the information from these sources and follow stories from Russian media too while being aware of censorship, propaganda and misinformation,” says Avakyan.

“Being originally from these places is helpful as we know the infrastructure and the places [mentioned].”

These local links have helped Avakyan and her colleagues cover stories and angles in ways unavailable to international media. For example, they’ve covered the story of an anaesthetist from Mariupol who helped terminally ill or injured people, especially children. HBO showed an interest. But according to Avakyan, the doctor trusted the Svoi City journalist from Mariupol with the story and it was translated into English to reach international audiences. In the first month of the full-scale invasion, Svoi City translated 40 stories and allowed them to be republished by others to extend its reach.

Fund journalism in a war zone

Before the war, 30% of Vchasno’s funding came from commercial sources. The conflict meant that the newsroom lost any ability to receive money from commercial channels and made some donor-funded projects irrelevant.

In the first few months after the full-scale invasion, Vchasno relied on the team’s own money. Funding from non-profit foundations such as the National Endowment for Democracy and European Endowment for Democracy has since come in. This has covered salaries and allowed for more stable working conditions for the staff. This funding has provided support for the website, which is now banned in Russia and has suffered multiple denial of service attacks. Svoi City’s website is similarly blocked in Russia and Russian-occupied territories.

“Right now, the hackers leave us alone,” says Vchasno’s Kyrylova. “We have ambitious plans. We need to build a new website and we are looking for professionals who can help us with social media development. We lost one of our social media managers who is now defending the homeland.”

They would also like to translate more stories into English and are looking for international funds and support to help expand their operations.

“It’s about connection and cooperation. Local journalists are the source of information and real stories,” says Davydenko. “It’s great when international media rely on these stories and exchange information. It helps to fight Russian propaganda. It’s important to tell the world stories from Donbas.”

Svoi City is looking for a coordinator to help it expand its English-language version, Svoi Global. Despite its local focus and its continued cooperation with international media, sharing information with international audiences is crucial to them. “Svoi Global will allow us to stay in touch with foreign journalists to help as much as possible with life stories and love stories,” says Avakyan.

The outlet is also planning the Svoi Fund: a platform for people who need any kind of help. Audiences will learn about these stories and about how they can get involved.

Even thinking about these plans is difficult right now. “Before the war, we were able to plan something for a year ahead; now it’s impossible to even plan for tomorrow,” Arakyan says.

Vchasno’s team is confident of a Ukrainian victory. When that day comes, its newsroom will focus on what it does best: journalism in the public interest. “After our victory, we will receive a lot of international support to rebuild our country,” Kyrylova says. “We plan to investigate how officials spend this money. But first of all, we want our victory, which we hope will come very soon.”

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time