Lecture: The Power of Platforms

More people get news via Facebook and Google than via any news organisation. These platform companies increasingly run much of the infrastructure of free expression, an infrastructure that enables us to do things, but they also structure our choices and impact existing institutions.

The news we get via platforms is still mostly produced by professional journalists working for news organisations. But the way in which we discover it, how content is distributed, where decisions are made on what to display, and who profits from our behaviour, is changing rapidly.

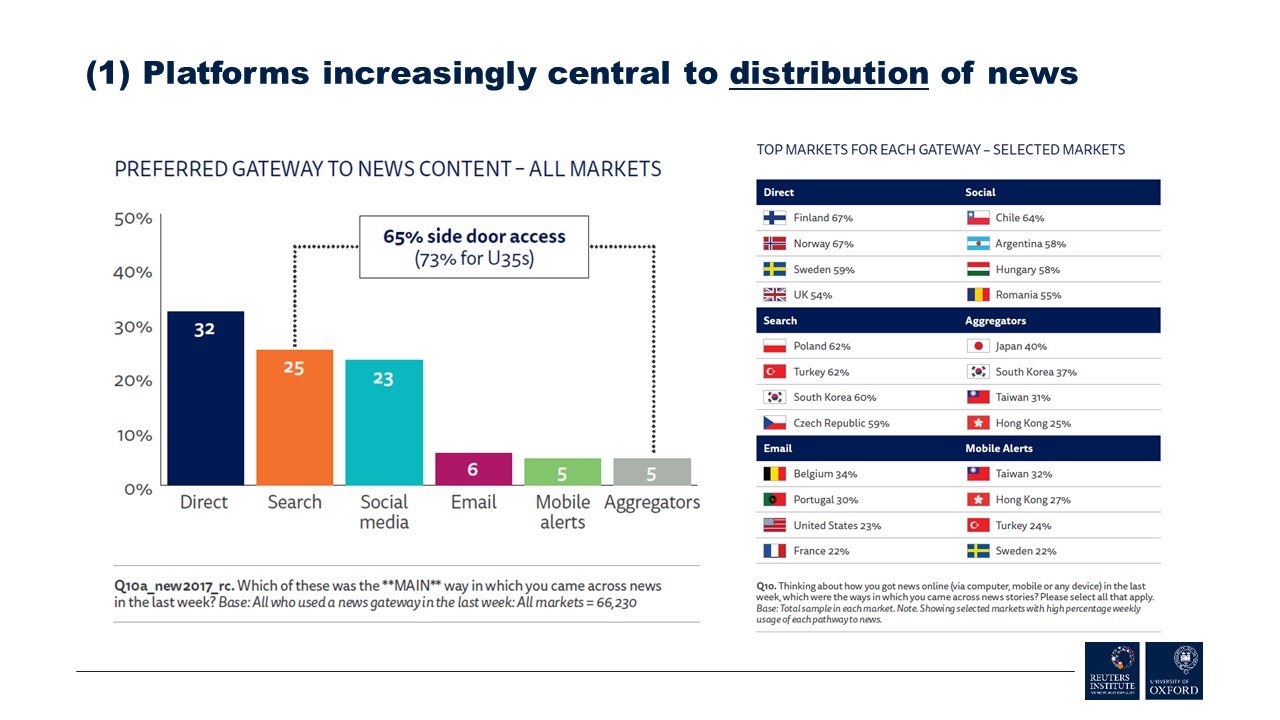

The rise of platforms means we have moved from having one set of dominant gatekeepers (publishers) to two sets of gatekeepers - publishers, who are still primary gatekeepers in terms of determining what is presented as news, and platforms, who are increasingly important in influencing distribution.

Contrary to fears of filter bubbles, polarisation, and social media distracting us from public affairs, a growing body of independent research documents that relying on platforms for news is associated with getting more diverse news, with a modest depolarisation effect, and with higher levels of political participation. These are broadly positive implications of the rise of platforms for many of us as individuals.

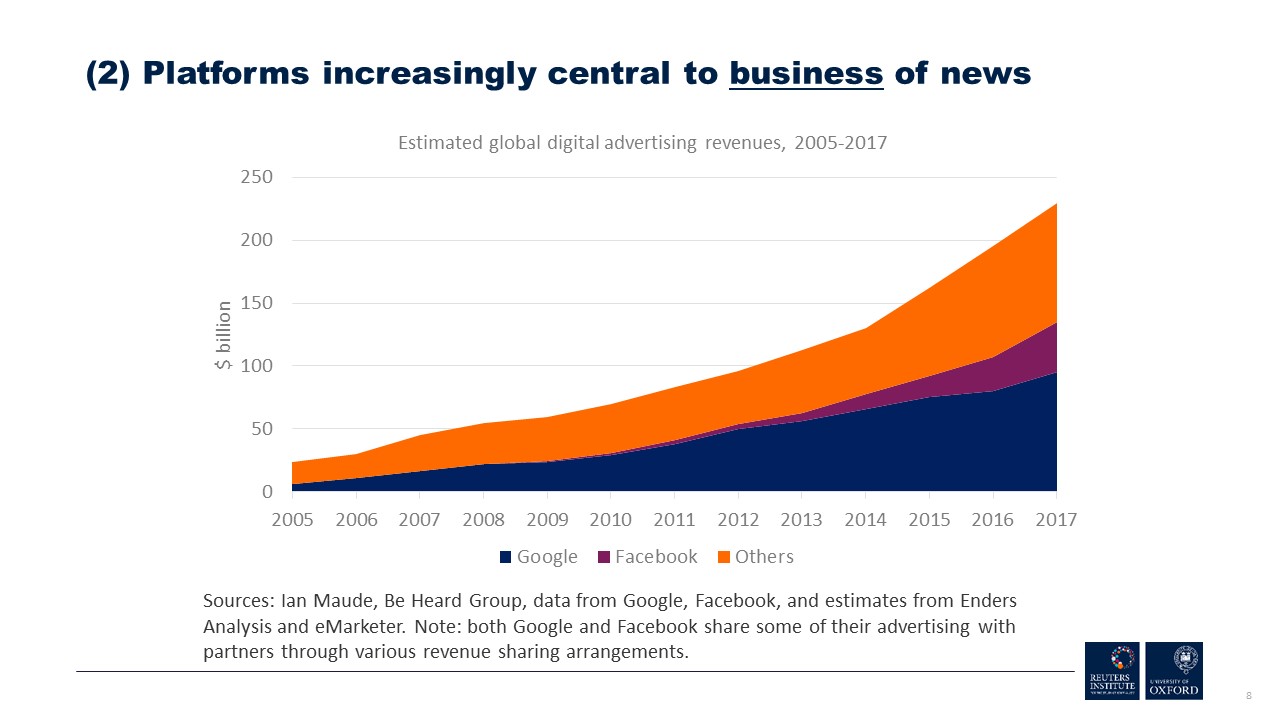

But as legacy revenues from print and broadcast decline rapidly and digital revenues grow only incrementally, large parts of the business of news as we knew it from the 20th century is at risk of becoming collateral damage from the rise of platforms. This demonstrates how the rise of platforms that in many ways empower us as individuals also have disruptive institutional implications.

News publishers we used to think of as mass media and as occupying the commanding heights of the media environment are now niche media increasingly reliant on platform companies that they work with, even as they are also often concerned about their growing reliance on them, and afraid of their power.

Platform companies have conventional forms of hard power and soft power, but also exercise new and increasingly important forms of "platform power", defined by the following five aspects in combination—

1. Platforms have the power to set standards that others in turn have to abide by if they want to be part of the social and technical networks the platforms build, enter the markets that they create, and take part in the transactions that they enable.

2. Platforms have the power to make and break connections within the networks of transactions that they enable by changing social rules (“community standards”) or technical protocols (search and social ranking algorithms).

3. Platforms have the power of automated action at scale as their technologies enable and shape billions of transactions and interactions every day, for both users, advertisers, and third parties.

4. Platforms have the power of secrecy as they operate as black boxes where outsiders can only see input and output on the basis of limited and biased data and only the platforms are privy to how the processes work and have access to more comprehensive data.

5. Platforms have power that operates across domains, fungible forms of power exercised in part through the large amounts of data they collect and the decisions they make about how to use it and who to share it with.

Power is not intrinsically a bad thing. Platform power is profoundly enabling, transformative, and productive. But it is power nonetheless, and tied to the organisational and strategic interests of the platforms themselves. Platform power is also deeply relational. Each of us as users - and every publisher and other third party - help make platforms powerful because they empower us (in specific ways) when we use their attractive products and services.

For publishers who want to pursue the opportunities that platforms offer, platform risk can only be managed, it cannot be avoided. Managing it will only grow more important going forward as platforms drive the development of many of the new technologies likely to become more important in the coming years, like private messaging services, voice-operated systems, and AR/VR.

The rise of platforms has in many ways empowered us as individuals, even as we have also—as and because we have embraced them—grown increasingly reliant on them. The rise of platforms has also challenged many incumbent institutions, including publishers, organisations who like us as individuals have to navigate the trade-offs of a situation where they are simultaneously increasingly empowered by and dependent upon platform companies.

This leaves us facing increasing urgency of having a conversation about platform governance, about what kinds of formal and informal rules and norms can help ensure platforms operate in ways that benefit all of us, that enhance our democracies, and not only their shareholders.

I hope this lecture offers an occasion to ask yourself what you think of platforms and their power, the ways in which we are empowered by them and dependent upon them, what you think we should expect from them, and how you think we can ensure their power is harnessed for good.

The lecture draws on material from Platforms and Publishers: A Comparative Analysis of Relations Between Digital Intermediaries and News Media Organizations, a forthcoming book by Rasmus Kleis Nielsen and Sarah Anne Ganter due to be published by Oxford University Press in 2019.

Photography by Karl Grupe of The Mango Lab