How I used generative AI to turn a powerful long-form story into an illustrated video

Image generated with Midjourney.

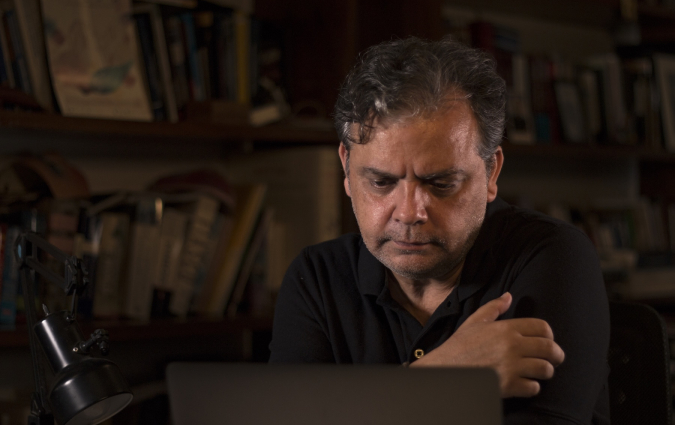

The Making of Edgar Matobato is a deep reflection on the confessions of a hired killer. Published as a long-form piece by the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) and reported and written by Columbia University investigative journalism professor Sheila Coronel, the article delved into the Philippines’ recent history of drug-related killings.

It was a story that needed to reach more people. I was deeply touched by it and wanted to know if there was a way to adapt it to other formats, such as video and audio so that it could reach audiences on the platforms where they consume content and information.

With Sheila’s permission, I experimented with generative AI to create multimedia elements to transform the story into this video. I used AI tools to generate images and turn photos into illustrations; create voice-overs for the story; turn the images into animation; and create haunting music for the soundtrack. Here is how I did it.

Picking voices and generating voice-overs

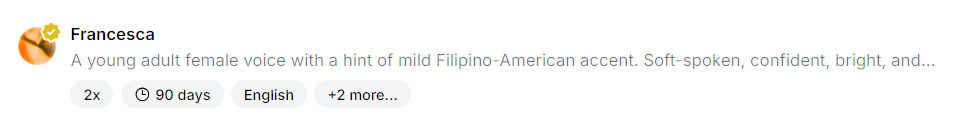

For the voice-overs, I chose to use Eleven Labs, a company that specializes in AI voice generation. The service has a free tier but access to different voices is limited to default options. For this project, I chose to subscribe to the Creator tier. It costs $11 for the first month and $22 for succeeding months. The paid tier allows a wider range of voice options for the project, including those with the appropriate accents for the story. For the main narrative of the Matobato story, I went with the Francesca voice, described as a “young female voice with a hint of mild Filipino-American accent.” It also costs twice the credits compared to the default available voices.

I also used a variety of other voices, all with Filipino accents, for various characters in the story.

The paid tier allows users to create Projects, which are used for longer-form initiatives such as podcasts and audiobooks. This allowed me to divide the story into chunks before converting them into audio. It also had an easy interface to assign particular voices to lines from the story.

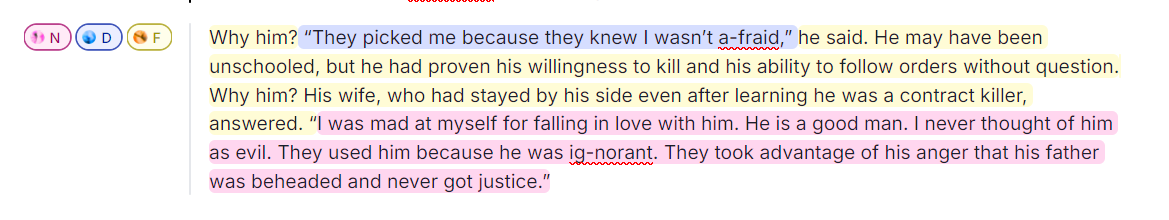

For example, this part of the story had three different voices: the narrator, Edgar Matobato, and Matobato’s wife.

The biggest challenge in generating the voice-overs is getting the synthetic voices to pronounce some words, mostly proper nouns, correctly. Getting around this takes listening to the generated voice and adjusting the spellings until it is right.

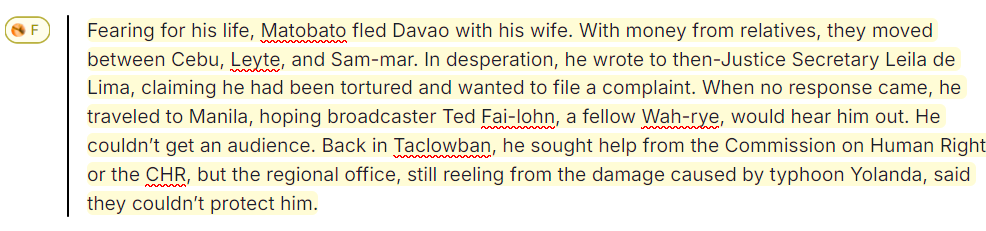

For example, I had to change the spelling of Samar province to “Sam-mar,” the surname of the radio broadcaster Ted Failon to “Fai-lohn,” and the name of the Waray people to “Wah-rye” to get the AI to approximate the correct pronunciation of those words.

Sometimes, the system would pronounce the same words differently. In one snippet, the pronunciation of ‘Matobato’ in the AI-generated audio differed from the rest of the story. I had to change the spelling of the name (Ma-to-ba-to) just for that snippet to make it similar to the rest of the audio.

The Creator tier of Eleven Labs gives the user 100,000 credits per month, which can be used to generate audio. The credit cost for each audio snippet depends on which voice model you use.

For the project, I used the Eleven Turbo 2.5 model, an older model that was about half as expensive as their cutting-edge Multilingual 2.5 model.

After much trial and error, generating the audio from the original 4,000-word piece cost around 50,000 credits or half of the monthly allocation for the Creator tier. The total length of all the voice-overs was about 33 minutes.

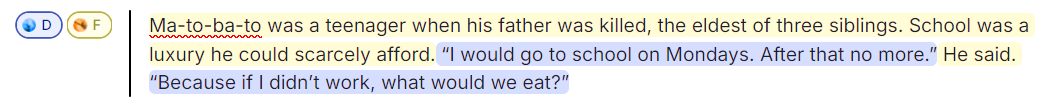

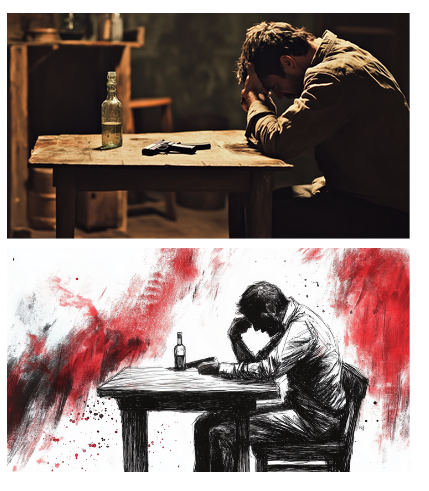

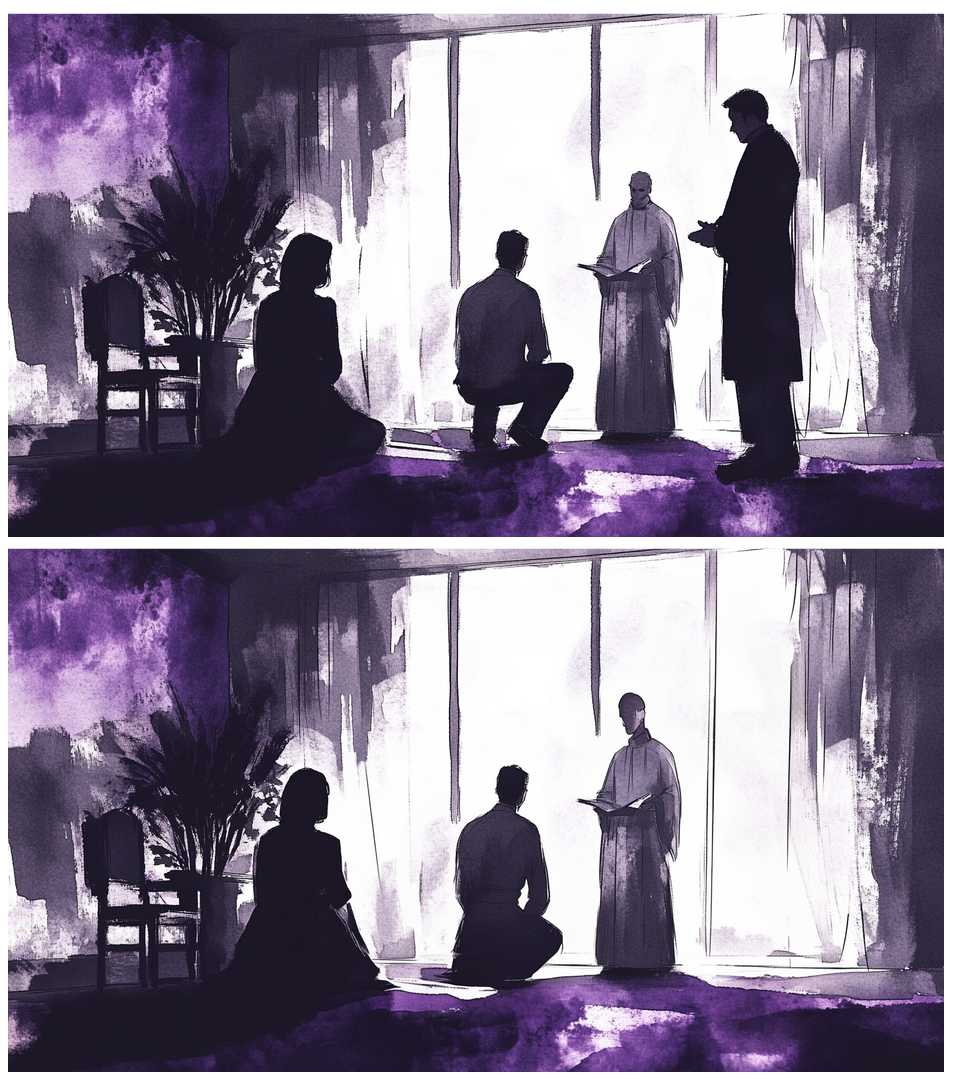

Finding the right image style

For the visuals, I wanted to use a style that would evoke the story’s original narrative while making clear to viewers that it was merely symbolic imagery. After some trials, I settled on the style of ink sketches with watercolour streaks. I did this by adding an instruction along the lines of: “in the style of a colouring book, clean lines, black and white ink, red watercolour streaks” to the end of every prompt.

Below: the same prompt, with the additional instruction: "in the style of a colouring book, clean lines, black and white ink, red watercolour streaks."

I tried several different image generation tools to figure out what worked best for the projects: Midjourney, which costs $10 for a monthly subscription; Dall-E 3, which is built into ChatGPT; and Imagen-3, which is built into Google Gemini.

I ended up choosing Midjourney for a couple of reasons. First, it consistently generated better-looking images compared to ChatGPT’s Dall-E 3 or Google Gemini’s Imagen 3.

The second reason is that because of the sometimes graphic nature of scenes from the story — a piece about a hitman detailing his experiences of killing people — guardrails built into the OpenAI and Google chatbots would occasionally flag the image prompts for content violations, a reminder that journalists sometimes need to talk about subjects that can run afoul of big tech moderation standards.

Generating images through meta-prompting

While I didn’t use any of the chatbots to generate images, ChatGPT was still useful in generating better prompts to use on Midjourney. I used snippets of the original story to generate structured, detailed prompts to then feed into the image generation tool. This is a technique called meta-prompting. The chatbot was able to identify crucial details like characters, settings, and symbolic imagery while translating abstract concepts such as fear, secrecy, or tranquillity into visual elements like lighting, shadows, and posture. With meta-prompting, I was able to create prompts with enough detail to effectively capture both the emotional tone and thematic essence of each scene.

In this case, my instructions to the chatbot were simple enough: “I am working on a project to turn an article into a video. I will give you snippets of the article, and I want you to return with prompts for a Midjourney image. Keep it short and succinct. Make the prompts symbolic instead of literal, for example, a close-up shot of a revolver on the ground. Give me three prompts each time.” I would then paste a snippet from the article in succeeding chats, and it would return sample prompts for me to check, revise, and use in Midjourney.

Editing and adjusting images

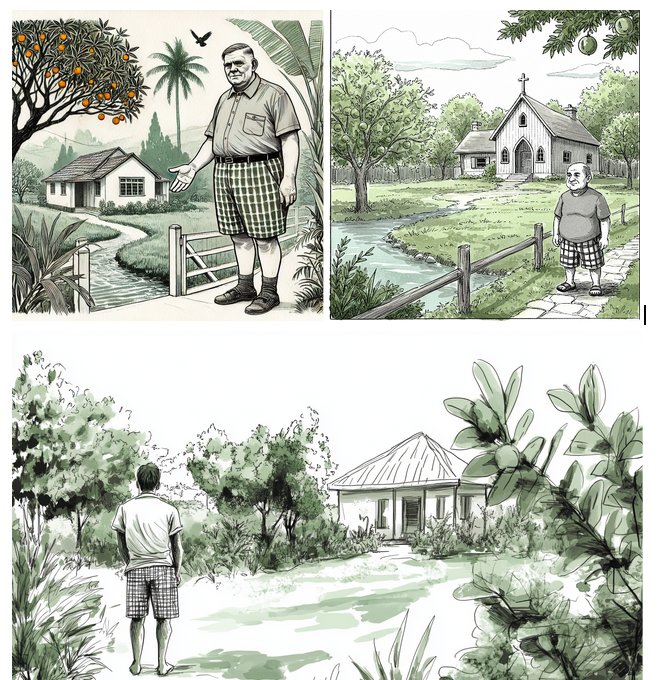

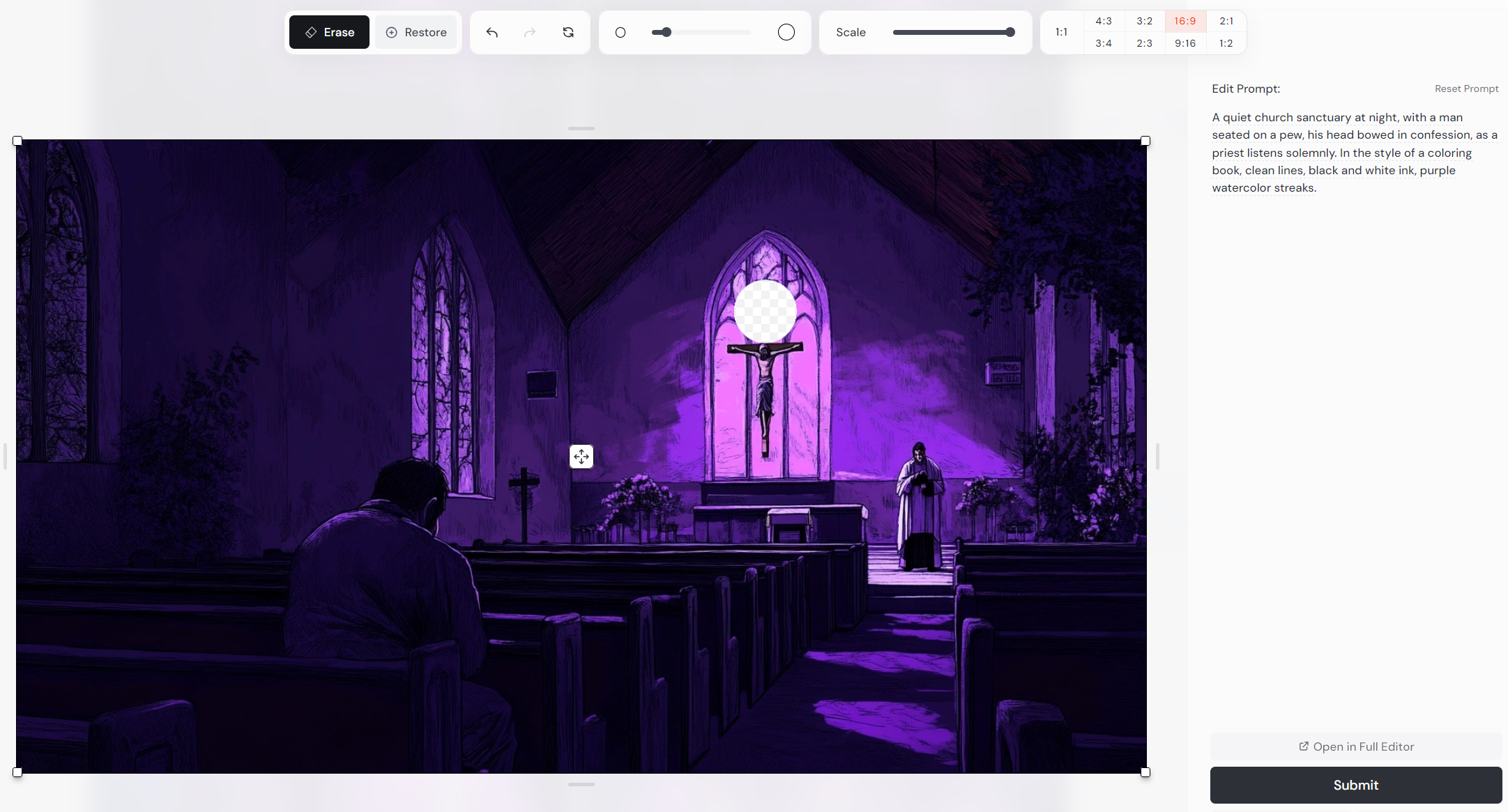

Another useful feature of Midjourney is its editor, which allows you to modify elements of the initial image.

This allowed me to adjust certain elements that did not look right. In this scene, I was able to make the crucifix in a key scene inside a church look more appropriate.

This image, meanwhile, had multiple tweaks: I got rid of a person who was not supposed to be part of the scene, I modified the look of the head of the priest, and I changed the position of the legs of the main character to remove his squat and make him kneel, as described in the story.

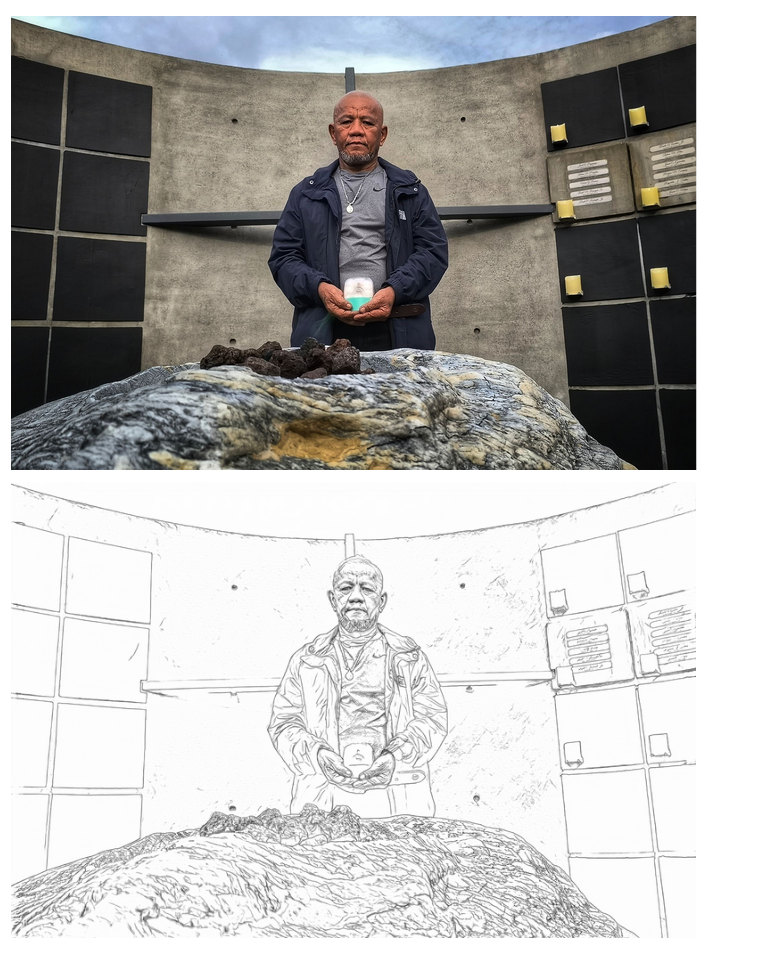

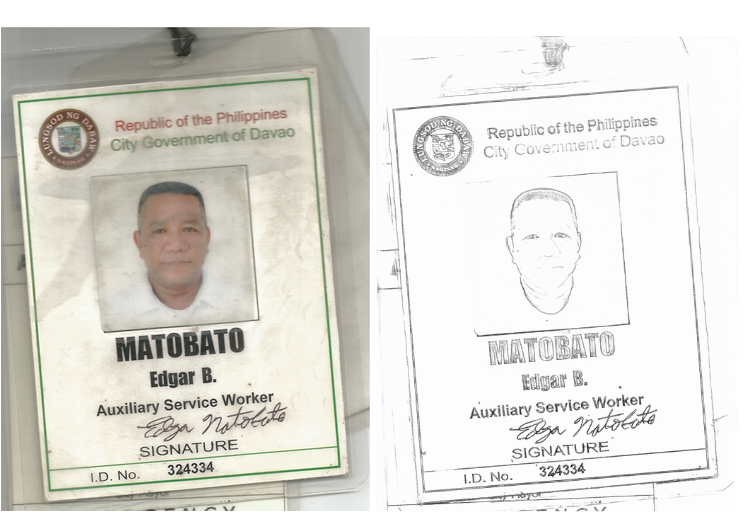

Turning photos into line art

The original piece featured photos of Matobato by Vincent Go, along with a picture of one of his old IDs. I wanted to include these in my video, but I didn’t want it to clash with the visuals that I had already generated. To make the photos more compatible, I used an image processor on Hugging Face to turn the photos into line art.

Using the editing and animation techniques described below, I was able to use both photo and line art versions of these images for the video.

Animating the images and editing the video

I explored the use of generative video services to turn the images into animation. However, none of the major generative video platforms – Sora, Luma Dream Machine, and Runway ML – generated useful videos from the images I generated. They would usually create something that would not be usable for me as a producer because it didn’t make sense, add extra elements that were not in the original images, or look aesthetically bad.

About one in five videos generated by the platforms were useful for me as a producer using these videos to build the story, like this video that added a camera zoom effect to the original.

Considering these were each about five seconds long, it would take considerable effort to come up with enough material to support a narrative longer than 30 minutes. There is a reason why the demo reels of AI-generated videos on YouTube are generally just a couple of minutes long.

Using text-to-image prompts with these video generators didn’t work either, because they couldn’t capture the art style from the Midjourney images, nor were the animations compelling.

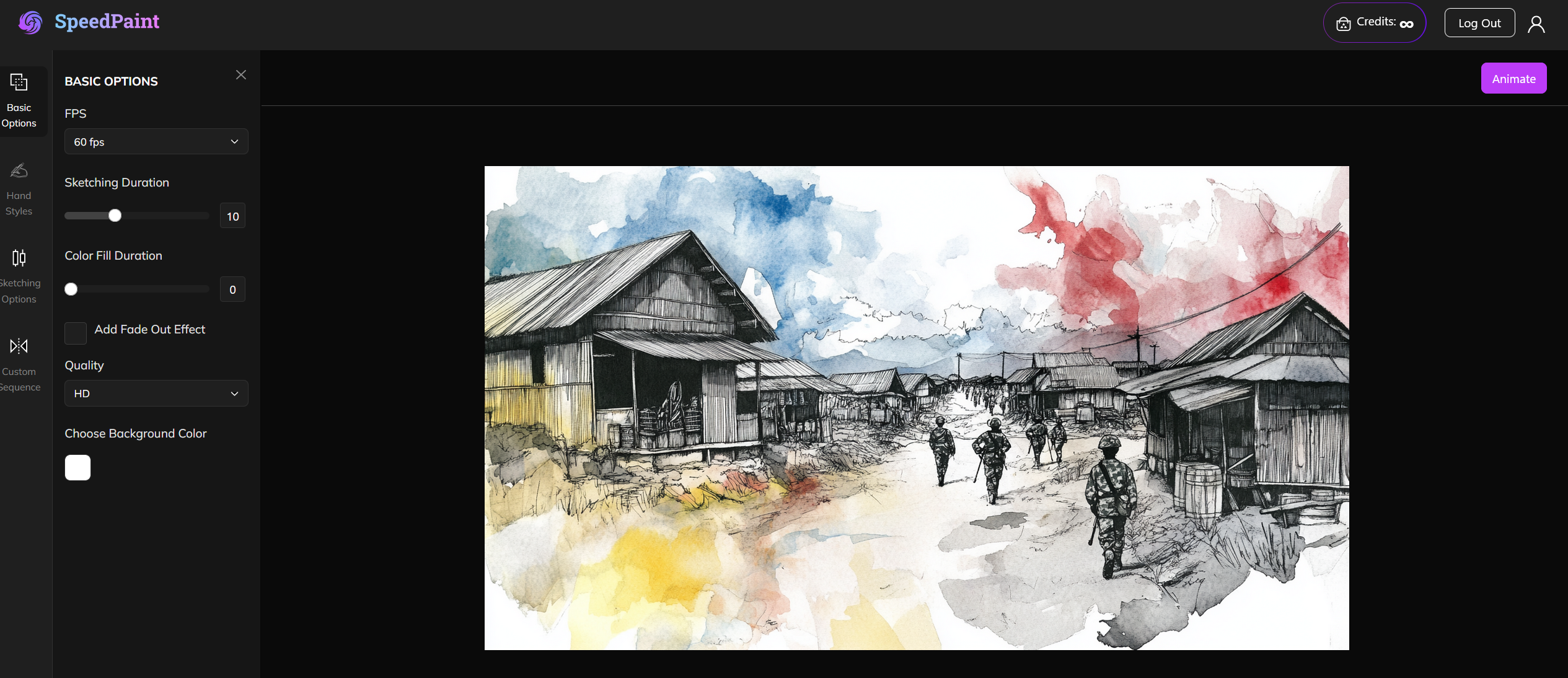

While looking for options, I stumbled upon YouTube videos of a speed painting animation app that used to be popular on Canva. It was no longer available on Canva when I tried it, but there was a website for the same app, Speedpaint.co, that was available for a $9 monthly subscription.

To use it, you simply need to upload your image and play around with the settings: the sketching duration, the colour fill duration, the sketch type (colour, grayscale, black and white, or neon blue), and the sequence of the sketch.

Hitting animate would result in a video being generated after a couple of minutes. The result was perfect for what I was trying to do.

The animations generated by the app were about 30 seconds each. For the final video, I slowed this down to ⅓ speed, which meant that each animation could last 90 seconds. If the audio segment was still longer than that, I simply used a freeze frame and applied the Ken Burns effect, a popular documentary technique for using images in video by pan and zoom movements, to extend the video further.

The speed paint animation was useful not just for the generated images, but also for the line art version of the original photos. By using a simple cross dissolve, a video editing technique that serves a transition between two images, it became an easy way to integrate original photos into the video.

Generating a soundtrack

For the soundtrack, I used Suno to generate simple piano music with the prompt: “Background piano music for a narrative podcast, slow, sombre, intimate, looping, spare.”

I found the first couple of tracks generated by the app a bit too fast and cloying, so they did not work for this project. The track I ended up choosing was sombre and intimate enough, though it did not loop. I simply applied fade-in and fade-out effects to the track to be able to use it over and over again in the video.

The human in the loop

I completed the work, alone, in two days. Knowing what I know now, it would probably take me just a day to complete it. Working with humans for these media elements – artists, illustrators, animators, voice-over talent, musicians – would’ve taken many more days, if not weeks.

While I used AI as a tool, the control remained with me as the producer throughout the process. I made all the creative choices, from curating the images to choosing the voice models to the editing, which was still fully manual and thus the most tedious part.

I used DaVinci Resolve to edit the video, though I could just as easily have used a more beginner-friendly editing program like CapCut or Microsoft Clipchamp to put it together. A more experienced video editor would probably have been able to complete the project much faster and frankly, the video would probably be much better.

How people reacted

I sent Sheila the video as soon as I finished it. “I was moved watching this rendition of my piece with art and music, providing it with more emotional depth compared to just text. I hope this version reaches audiences that would otherwise not read a 4,000-word story. We need more experiments like this,” she said.

She was surprised by the quality of the voices, as were journalism colleagues from the Philippines who watched the video. They were struck by the slight hint of a Filipino accent in the main voiceover, which they felt added to its human quality.

Interestingly, colleagues from outside the Philippines weren’t too taken by the voices. “Too monotonous and puts me to sleep,” one said. Others, meanwhile, suggested playing the video at 1.25x speed, which they said made it better, but still not as good as human.

Many of my colleagues were stunned by the quality of the images from Midjourney, which they felt added to the video. But there was some pushback from followers of the PCIJ, who said they were disappointed in the use of generative AI images, raising ethical concerns such as the platforms’ unauthorised use of artists’ work.

For his part, artist Joseph Luigi Almuena, who has animated PCIJ’s investigative reports, said the first thing he would ask is: ‘What is the AI image for? And who is it for? Will it serve the public good?’

I think this effort shows the potential to do just that, by turning a narrative text into a format that could introduce an important story to new audiences.

Broadcast journalist Jessica Soho, a longtime news and documentary production executive who anchors the most popular television program in the Philippines, said the final product sounded more like a podcast rather than a narrative video. Still, she sees the potential for using these technologies for newsrooms looking to broaden their audiences.

Indeed, media outlets and even individual journalists could pick and choose which elements here would be appropriate for them, depending on their resources, their strengths, and the attitudes of their audiences. Some could use all of it. Others could use generative AI images with human voice-overs for maximum impact. Some could find uses for synthetic voices to turn their long-form narratives into podcasts. Still, others could simply use the animation techniques here to turn their photos into video material.

With this experiment, I hope I was able to show journalists, producers, and newsrooms around the world how these various generative AI tools could be building blocks to transform written news articles and help them tell compelling stories in new ways.

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time

signup block

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time