EU media literacy drive should address poor algorithm awareness

This week is European Media Literacy Week, an initiative from the European Commission designed to “underline the societal importance of media literacy and promote media literacy initiatives and projects across the EU”.

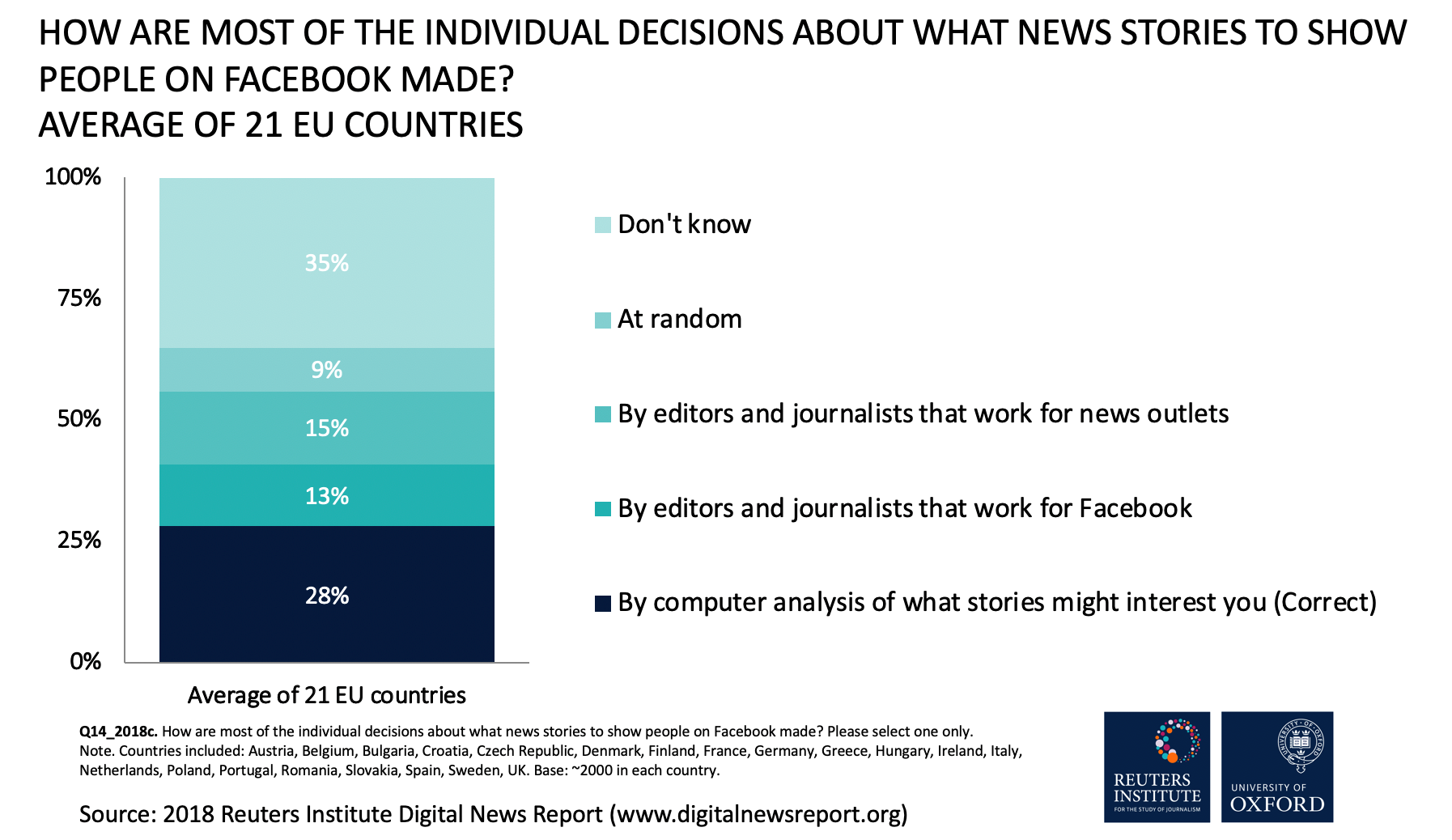

Our research, based on data from the 2018 Digital News Report, suggests that particular focus on social media is needed. Just 28% of people across a sample of 21 EU countries know that algorithms select most of what we see on the Facebook news feed.

Media literacy has been much debated in recent years, especially following widespread concern over misinformation, disinformation, and low trust in the news media. There’s disagreement over what constitutes good media literacy, but given that social media is now a key part of many Europeans’ information diets, an understanding of how social networks make decisions about what to show people is an important component.

As part of our 2018 Digital News Report, we used an online survey across 21 of the 28 EU countries to measure how much people know about how the news is made. One question asked people how most of the individual decisions about what news stories to show people on Facebook are made.

Just 28% of people were able to correctly specify that most of the individual decisions about what news stories to show people on Facebook are made by computer analysis of what stories might interest them.[1] Perhaps more surprisingly, the same number (28%) incorrectly thought that most news stories are selected by editors and journalists, either working for news outlets (15%) or for Facebook (13%). One-in-ten (9%) thought that news is selected at random.

As ever, there are country differences. In Finland, 39% answered this question correctly. In France, it was 19%. People also do better at answering questions on other topics (e.g. 48% are able to identify that the public broadcaster does not primarily depend on advertising for financial support). But leaving these differences to one side, it is clear that knowledge of how Facebook works is less widespread than it could—and perhaps should—be.

Calls for more media literacy are sometimes met with eye-rolling. There can be a tendency to see more education as the solution to every complex social problem. Others, perhaps, simply don’t find it interesting enough as a response. Yet, our own research has shown that people with higher levels of news literacy do seem to navigate the media environment differently. They are, for example, more likely to consider the news source, and less likely to consider the number of comments, likes and shares, when deciding whether a news story on social media is worth their time.

Media literacy is not a silver bullet, and increasing it will not make problems like online misinformation and low news trust go away. But in light of the fact that people with higher levels of media literacy do seem to behave differently, we should be careful not to dismiss it as a viable intervention.

[1] We intentionally avoided using the word ‘algorithm’ given that this is a technical term that may have confused some respondents.