This chatbot helps tell the story of how women are affected by drug trafficking in Paraguay

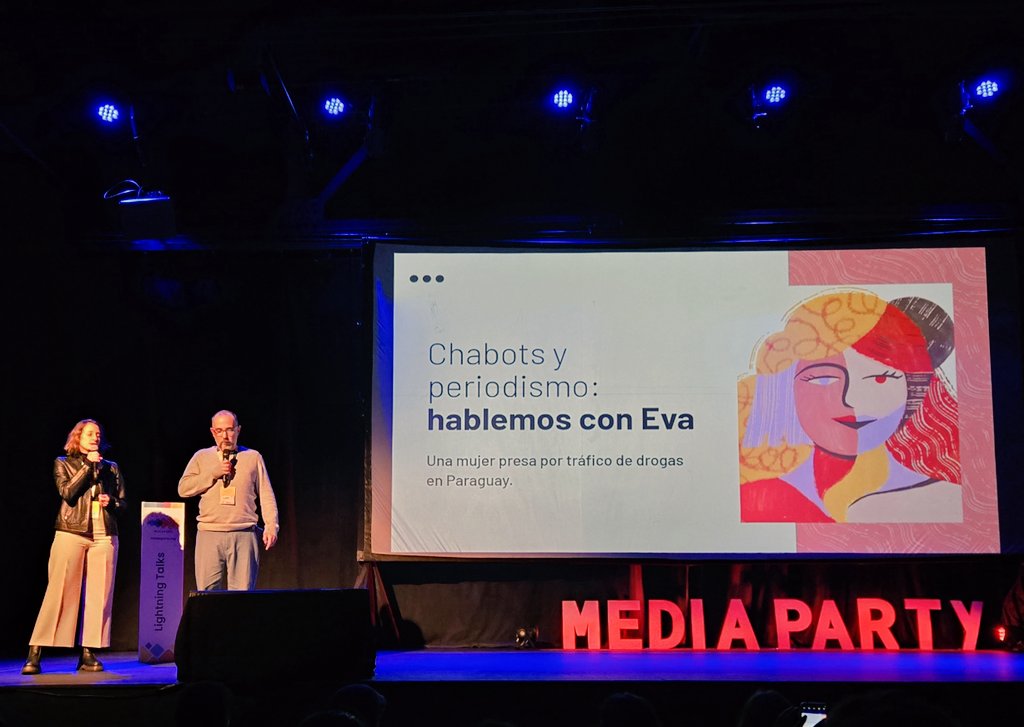

Juliana Quintana and Sebastián Hacher presenting Eva at the Media Party summit in Buenos Aires.

“Hi, I'm Eva. I'm going to be in prison here for ten months.”

This is how the story (or rather the conversation) begins with Eva, a chatbot developed by Paraguay’s independent, digital-first newsroom El Surtidor to find a different way to tell the story of how communities, especially women, are affected by drug trafficking.

According to El Surtidor, often shortened to El Surti, more than 400 women are in prison for drug trafficking and related crimes. Four out of ten female prisoners in the country are accused of breaking a narcotics law.

El Surti reporter Juliana Quintana has spent years reporting on this topic, interviewing numerous women imprisoned for drug offences and those who have served their sentences.

However, using her reporting to help build a chatbot to tell the story of these women is a new experiment for Quintana and the newsroom. Audiences can choose which questions to ask Eva, leading them down one of several conversational paths to reveal different aspects of her story. The newsroom hopes it will “make visible the disproportionality in the treatment of crimes that arise from punitive drug policies” and “reflect on the circumstances of women deprived of liberty that involve, mainly, discrimination, exclusion and sexist violence.”

I spoke with Quintana and journalist, UX consultant and conversational designer Sebastián Hacher to find out more.

Q. Tell me about drug trafficking and micro trafficking [the trafficking of small quantities of drugs] in Paraguay. Why is it an important topic for El Surti to cover?

JQ: There is an irony in Paraguay’s famous war against drugs: it imprisons women but ignores those who grow rich and even hold positions within the state in this narco-culture.

Microtrafficking is complicated because marginalised women often don’t have a lot of work opportunities and the state isn’t interested in helping them. They have children, and maybe their partner abandoned or abused them. A lot of women told me that they didn’t want to traffic drugs in the beginning but were pushed by their partners to do so. They feel responsible for what they did, but you realise this is part of a bigger discourse. The state’s responsibility or absence of public policy isn’t talked about.

Q. Why make a chatbot?

JQ: There’s a lot of great reporting on narco-culture, but we wanted to find a new angle with a new narrative from a gender perspective and to show the consequences for the women involved and the powerful people who get rich from drugs.

People can have a passive experience with an article. With the chatbot, it’s like you are sitting at a table with an imprisoned woman having an intimate conversation. The answers are the exact words she used [in an interview] with very little editorial interference.

SA: When you chat with Eva you are chatting with a real person. Conversational experiences allow the audience to construct the narrative part of the news. You can co-design the trajectory of the story with the audience.

Eva is a tool to allow people to understand how this person arrived there. You read stories like this every day and here you are learning the other part of the story.

Q. Juliana interviewed 10 women for this project, with most interviews taking place inside Buen Pastor prison in Asunción – not an easy place to access. The chatbot Eva is based on the answers of one of these women, whose name has been changed. Tell me about the interview process and how you found Eva.

JQ: Each interviewee was asked more than 50 questions from the same questionnaire [to provide structured data to power the chatbot]. To design the questionnaire, we started with what a conservative member of the audience or someone who would mistreat Eva would ask [in order to emphasise the elements of Eva’s story].

We had to imagine a lot of questions that the audience might ask, like, 'What’s your favourite food?' Interviewees found questions like this funny. We had questions on education, health, and family, as well as how they imagined their future and life in prison.

I tried to pick a subject who was different in terms of what people typically imagine as the subject of stories about organised crime and human trafficking, but who is also going to ‘represent’ a large proportion of women who are incarcerated.

Eva’s interview was the longest and wasn’t planned at the beginning. I was clear with her about the impact and scope of the project. She wanted to expose her story to feel more humanised. She had never been interviewed before.

Q. The interview used for the chatbot was three hours long. What were the next steps and how did you build the chatbot?

SA: We needed large interviews to provide the information on which to build the conversation flow. Every word from Eva was a piece of gold that she gave to us. Our mission was to take care of that. We designed a very long flow of questions and responses [using Voiceflow, a tool for building AI agents].

The design process took two to three months because we wanted to create the experience of a natural conversation with Eva without using GenAI. Everything in the chatbot is written by humans. There are around 55 types of questions with hundreds of variations the audience can ask and the chatbot has 120 answers. We used artificial intelligence [ChatGPT 3.5] to make the natural language processing (NLP) and train the chatbot to understand the different ways the audience might ask the same question.

JQ: I transcribed the whole interview manually because AI doesn’t understand the language used, especially Yopará [a mix of Spanish and indigenous language, Paraguayan Guarani]. I sent the transcript to Sebastian and co-designer Axel Marazzi, who understood the details that couldn’t be included in Eva’s answers.

The text was then imported into the workflow and we did some internal trials to see if the AI was going to be used for questions and answers or only in the questions. We decided that AI could only be used to help us write the questions for users of the chatbot and select the answers because we were concerned about hallucinations or that using AI to construct the answers might turn Eva’s experience into cliches. We didn’t want AI to contribute to making Paraguay or her rich story invisible.

If an audience member asks a question that Eva doesn't know how to answer, she says something like: "I didn't understand. I think I'm listening wrong. Shall we go again?" or she redirects the conversation towards a related topic. She is only trained to answer questions that are related to her story and her situation. That is why we designed a suggested path that leads the audience to ask questions that actually relate to this investigation.

Q. Were there any challenges to building a chatbot to tell a story on this topic?

JQ: We focused on protecting our sources, changing names and background details. They are going through the legal process and have to tell their stories over and over. It’s not the purpose of our work to interfere with their lives – it’s to help.

Most of the incarcerated women in El Pastor speak Yopará and some Guarani. In the chatbot, we wanted to preserve the way that Eva speaks and the way we speak in Paraguay, so we worked hard on her voice. If the chatbot used AI to generate Eva’s answers it could neutralise the language and smooth out its regional character. We realise that this might limit us to a Paraguayan audience, but Eva is Paraguayan.

Q. What feedback has the chatbot garnered from audiences?

SA: We launched in September and there’s been more than 10,000 interactions with Eva. The chatbot has understood 85% of what people ask. We’ve read a lot of the conversations – maybe 200 – because then we can improve Eva’s model and add some content.

We’ve tried to be very human with Eva’s story. Around 55% of people ask her about her family. People write ‘ciao’ or ‘I wish you all the best for the future’. They know they are talking to a chatbot but they still say thanks.

Q. What influence has this project had on your ideas for AI for storytelling in journalism?

JQ: I don’t know if I would have come up with this idea for telling the story of a woman imprisoned for drug trafficking. We have to be very careful with [how we use AI in] women or human rights coverage. We don’t want technology to answer for these people or to decide what stories are going to be told. I think Eva has shown that if you are very, very, careful and you want to power your story with AI, you can. You can use very little AI and start with that. This was an exploration and I think news media are going to come up with better and better chatbots to tell stories and we will realise where we can improve the construction, the interviews and the reporting behind them.

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time

signup block

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time