In this piece

Lessons from Brazil on how to better cover the environment and the climate crisis

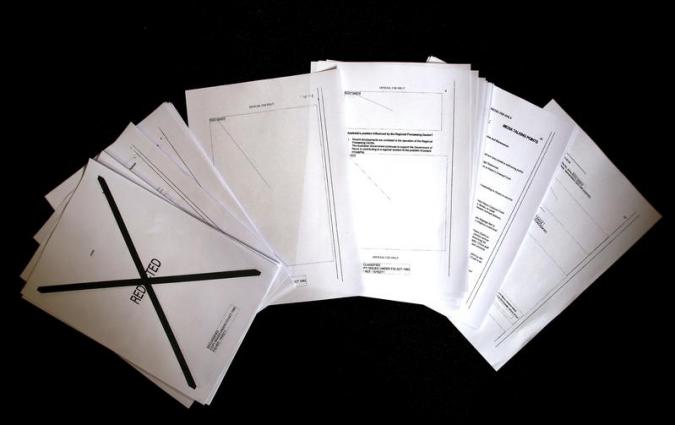

The Amazon rainforest, Maró Indigenous Land. Photo supplied by Flavio Forner.

In this piece

1. Who tells it: every story is a climate story now | 2. What is required: scientific literacy | 3. How to tell the story: solutions journalismIn February this year, secretary-general of the United Nations António Guterres said that climate disruption, pollution, and accelerated loss of biodiversity were the critical elements that make up what he called the “defining issue of our time".

In Brazil – home to the Amazon rainforest, the Pantanal wetlands, and diverse species of flora and fauna – environmental journalism is not a new beat. But it is a beat that has had to evolve rapidly in the past few years: first in response to global environmental crises unfolding on our own doorstep, and now in response to a government that has rejected science in favour of policies that protect unsustainable commerce.

During my time at the Reuters Institute, I interviewed eight leading environmental journalists in Brazil, as well as Visiting Fellow Wolfgang Blau, about how we should be responding to the climate crisis. The full result can be find in a paper you can download here. In summary, they mentioned three fundamental questions newsrooms should ask themselves about environmental journalism: who should tell this story? What should they be expected to know in order to tell the story accurately? And how should the story be told?

1. Who tells it: every story is a climate story now

The climate crisis needs a new breed of journalist, according to Blau, former COO of Condé Nast and a Visiting Fellow at the Reuters Institute. “We need journalists who are systemic thinkers, who understand how large-scale transformations work, what the obstacles are, what the methods are,” he said. “We need journalists who understand policies, which is not the same as politics. We'll find many journalists who are really good at covering elections. We'll find fewer journalists who understand how policies are being made and implemented.”

All of this in one person may be a tall order, but educating journalists across the board so that they can work together is not. “No topic is exempt from the effects of the climate crisis. There is just no area of society or area of journalism that would not already see changes that have to do with the climate crisis,” he said.

Breaking away from the idea that a single desk or agenda is responsible for environmental news is crucial. Environmental coverage cannot be the exclusive purview of one group in a newsroom; it must be on every journalist, editor and media owner’s radar. This will require training.

Daniela Chiaretti, environment reporter at Brazil’s biggest financial newspaper Valor Econômico, said environment desks should also be doggedly “local” in their approach to who sets the agenda. “I don't like the manipulated agenda that comes from northern countries for us. We need a look from the Global South, to our own problems, which are much more similar to Latin America and Africa than to the UK, for instance. There's been a lot of manipulation of the climate agenda by some news organisations. Climate journalism in European countries is not similar to our climate journalism. In Europe there is no discussion of inequality or climate injustices that are part of our reality. We can't just have the European vision. As journalists we can't simply translate what happens there,” she said.

2. What is required: scientific literacy

If journalistic coverage of the climate crisis is no longer the sole responsibility of environmental reporters, then journalists and editors across every desk will need a basic grasp of climate science.

Workshops, online seminars and lectures on the subject are widely available, and newsroom managers should mandate this training. Of course, this doesn’t mean it isn’t still worth having a specialist on staff. If you do, ensure that the newsroom makes good use of their talents. Chiaretti helps her colleagues at Valor by collaborating on stories, consulting in planning meetings, and reading through their articles to provide expert overview. “I do it with great pleasure,” she said.

Where budget constraints prevent hiring a specialist like Chiaretti and don’t allow the time for in-depth data and investigative journalism these stories sometimes require, consider partnerships or joint productions with small independent newsrooms specialising in this content, like InfoAmazonia. You could either republish their content, or set up collaborative projects.

Failure to grasp the complexity of these stories can lead to oversimplification and overemphasis on the wrong things. For example, we frequently see coverage about individual lifestyle changes we should make to address the crisis. This obfuscates the real game-changer: policies to hold a powerful minority to account, like the 20 companies responsible for a third of all energy-related carbon dioxide and methane worldwide.

3. How to tell the story: solutions journalism

Several of the journalists I interviewed referred, directly and indirectly, to a style of journalism that has been providing good results worldwide: solutions journalism. Far from focusing on positive stories that obscure the facts, solutions journalism aims to holistically cover how people are responding to problems.

“We can't have a negativist agenda and only talk about what doesn't work because then journalism doesn't fully fulfil its social function,” said André Trigueiro, special reporter and presenter at TV Globo and columnist at Rádio CBN. “We need to show what doesn't work, but the balance of journalistic coverage presupposes [giving] perspectives. We need to be a showcase for solutions to inspire people. Bringing solutions helps to increase the audience.”

The 'SoJo' concept is still largely misunderstood among journalists in Brazil, even among the top journalists interviewed for this paper. Experts at the Solutions Journalism Network define the practice as a story that:

- can be character-driven, but focuses in-depth on a response to a problem, and how the response works in meaningful detail

- focuses on effectiveness, not good intentions, presenting available evidence of results

- discusses the limitations of the approach

- seeks to provide insights that others can use

- addresses the limitations, uncertainties and costs of the response

It is not a technique that puts journalists in the position of telling society what is right or wrong. Instead, it provides information about alternative approaches to societal problems based on initiatives that can show their results.

Experts argue that solutions journalism stories are deeper and more comprehensive than those that merely highlight the problem. They also create a connection with communities, and stimulate feelings of hope.

In the words of Sônia Bridi, special reporter at TV Globo: “We must write about the dangers, but if we don't help people to find a solution – a path to know how they can engage in a positive way – we only sow despair, and despair leads to denial.”