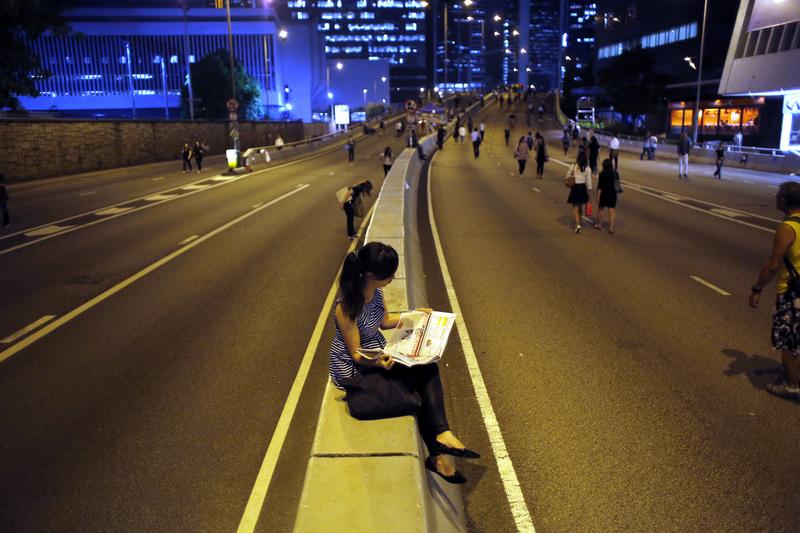

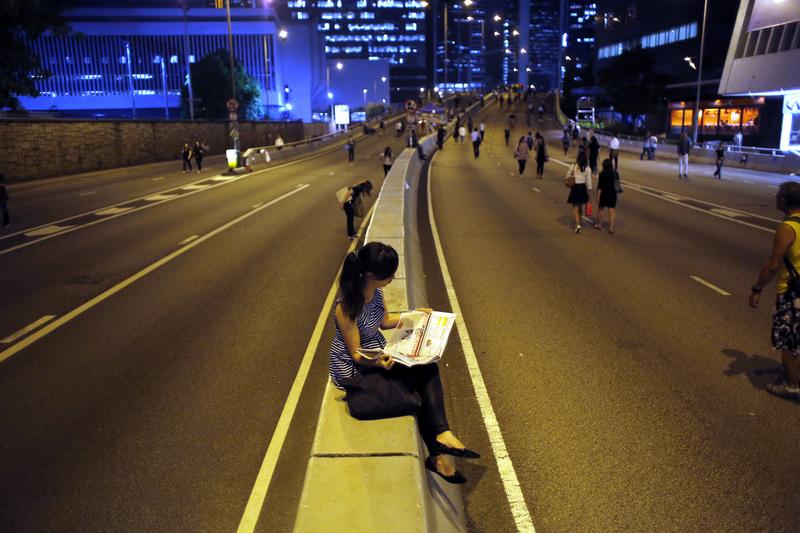

A pro-democracy protester reads a newspaper, Hong Kong, 2014. REUTERS/Carlos Barria

A pro-democracy protester reads a newspaper, Hong Kong, 2014. REUTERS/Carlos Barria

In March 2020, as COVID-19 spread around the world and political leaders began to realise that an immediate response to the pandemic would involve personal sacrifices and public action, politicians and their directors of public health policies took to stadiums, lecterns, and cameras to speak about the need to stay home, shut schools and nurseries, ration access to grocery stores and health services.

The men, and they were usually men, spoke of social cohesion and a need to act selflessly and responsibly. The women, and they were usually women, who took on the greatest burden on housework, childcare and responsibility for ageing parents, sighed, took a deep breath and got to work.

News exists in the context of the audience (Fletcher and Nielsen 2017a) and, this year, the audience have experienced the social upheavals of the year very differently and have had their concerns addressed very differently. But in a year full of change, the underrepresentation of women in much of the news is not one of the things that changed.

Luba Kassova’s comprehensive look at the women in media during the COVID-19 crisis highlights just how the media in much of the world has failed women in the content it produces (Kassova 2020). Her report documents the extent to which women’s voices have been missing from media coverage of the crisis, even as women feel the impact of the pandemic and associated lockdowns and restrictions the hardest.

Her findings echo Gaye Tuchman (1978) who four decades ago documented what she dubbed women’s ‘symbolic annihilation’ from the media and noted that most media portray women, if at all, in traditional roles: homemaker, mother, or, if they are in the paid workforce, clerical and other ‘pink-collar’ jobs. Such patterns have been documented time and again by the Global Media Monitoring Project’s regular ‘Who Makes the News’ reports, most recently in 2015 (Macharia et al. 2015). And as the long-term impacts of COVID-19 resonate through society it is clear that women have been hit the hardest financially.1

This report takes a look at the other side, not the news itself, but the people who use it, and presents a bespoke analysis of how women around the world consume and perceive news, based on data on audience behaviour from 11 countries featured in the 2020 Reuters Institute Digital News Report: Kenya, South Africa, South Korea, Hong Kong, Japan, Mexico, Brazil, Finland, Germany, United Kingdom, and United States. We have selected these 11 to represent as wide a geographical base as possible, and cover some of the richest and poorest countries in the report.

The present work builds on the Digital News Report and associated research, including the Women and Leadership in the News Media 2020: Evidence from Ten Markets factsheet (Andı et al. 2020) we published on 8 March 2020, in which we documented gender disparities in leadership on the premise that top editorial positions in major outlets matter both substantially and symbolically, as the personal experience of top editors will in part sometimes influence the decisions they make, building on decades of work documenting gendered patterns in news coverage, news work, and promotion inside news organisations (e.g. Franks 2013; Callison and Young 2019).

Our report brings audience data and other evidence to a wider debate about whether the media industry is fair to women: whether they are treated with respect as sources of information and as experts, whether the issues that impact on them are treated honestly and fairly.

The report also includes country profiles which look more closely into issues of media and gender in those countries, including discussions on newsroom gender balance and examples of new and innovative media aimed directly at women. It looks at some of the biggest debates that have happened in those countries over how women are portrayed, discussed, and treated by the news industry.

The aim of this report is to provide data on women’s news consumption but also to paint a picture of how women interact with news at all levels, and hopefully provide journalists, industry leaders, governments, and policy makers who want to reach women with some ideas on how this may be done.

As the country profiles show, a growing set of women-led protest movements against femicide, sexual assault, and online harassment around the world have created a new debate around how the news portrays women, and new conversations about who is in the newsroom deciding the agenda and framing the news. While news reporting has sometimes played an important role in these debates, it is also clear that many of them are driven by feminists who use social media as activist tools to speak out and organise against sexism and misogyny, sometimes in the news media too (Mendes et al. 2019). We see this with #MeToo, but also important specific mobilisations around e.g. #EleNão in Brazil, #ProtestToo in Hong Kong, and many more.

This is part of a broader trend where historically disenfranchised populations in many countries are using digital media to work around often white- and male-dominated established news media spaces they have long been excluded from. Our audience data demonstrate that women engage with established news media in ways that are sometimes quite different from those in which men engage with news (Jackson et al. 2020).

By combining our unique, cross-country data on news and media use with country profiles capturing key parts of developments on the ground in countries around the world, this report aims to contribute to the continued important conversation around women and news.

First, women are citizens and access to accurate, timely news is necessary for democratic participation. It is also important as a channel for information, to give people information about regulations, services, rights, and protections that affect them directly.

There are many correlations between news and participation in political life. As Christine Benesch pointed out in 2012, countries highest in political and economic gender inequality also exhibited the largest gender gaps in news consumption. In other words, where women are more represented in the political system and therefore stand to gain more perceptible benefits from being politically informed, and where they also have access to time and resources that allow them to turn their attention to news, they are more likely to do so at rates similar to men.

So news matters. This is true at all times but particularly so during a pandemic when there are extraordinary controls of people’s behaviour and movements, and new advice on how to react to health-related issues. It has also raised new dangers for women of domestic violence and abuse in homes where they often feel trapped with their abuser.

A UN report on the impact of COVID-19 on men and women highlights how it has affected women disproportionately, ‘forcing a shift in priorities and funding across public and private sectors, with far-reaching effects on the well-being of women and girls’. It also warns that women worldwide have been hit harder economically by the crisis and that their lesser access to land and other capital makes it harder for them to weather the crisis and bounce back. In other words, there is a real danger of the pandemic leaving women weaker, poorer, and pushed further out of the political sphere than they were before.

In those climates it is vital that women have access to news and information that will help them survive and access information about how to recover. This can be immediate, practical information: for example, places of refuge and tweaks to emergency legislation that allow them to leave their home and stay with a friend if they are in danger, even in a lockdown. And it can be broader: news about the efficacy and health impacts of vaccinations, about school closures, and the trustworthiness of politicians.

News, and in particular news organisations, can also serve another more social function, as a source of companionship, solace, identity, and entertainment. Again this is true at all times but particularly so this year when the restrictions necessitated by COVID-19 have upended so many traditional networks and community spaces.

Men and women consume news differently, at different times of day and in different ways. The traditional print model revolves around the idea of a man reading the paper at the breakfast table, with his wife preparing breakfast, possibly with the radio or television in the background. Traces of these habits still remain in some countries, and many editors in Latin America, especially in Mexico and Brazil, find that print is still more popular among men, while women use more TV and radio, but overall patterns of use are changing.

Patterns of news consumption now are determined by access to mobile data, broadband, and enabled devices, as well as the commute to work, types of employment, and, crucially, time available. In a study of news avoiders, Toff and Palmer (2019) look at news usage among women in the UK, highlighting the fact that the way women consume news has often been shaped by their domestic responsibilities. Many of the women the authors spoke to also spoke about how news is a low priority for them: not something they believe they need in the course of their everyday life, and something that should not supersede other tasks.

News did not provide them with what they needed: neither escape nor information they felt they could utilise, and the emotions it invokes are negative. Instead, avoiding the news was often a strategic decision by busy caretakers to narrow their ‘circle of concern’.

This structural inequality in news consumption has carried on during this year’s coverage of COVID-19. A survey by the UK COVID-19 news and information project shows that, in April 2020, roughly equal proportions of both men and women in the UK said they were accessing COVID-19 news at least once a day on average. By late June, a gap had emerged, with women less likely to regularly access COVID-19 news than men (Nielsen et al. 2020b).

As noted before, this is in line with previous research documenting that men often consume more news than women, and an illustration of how the dissipation of the ‘rally around the news’ and surge in news use early in the crisis comes with a return to longstanding structural inequalities in news use, perhaps exacerbated in cases where the pandemic has reinforced existing inequalities discussed above. By the end of August, the gap in the UK was still 6 percentage points.

It is clear that one of the structural inequalities COVID-19 has increased is women’s ‘time poverty’. Even before the pandemic women did nearly three times as much unpaid care and domestic work as men, and this year, as schools and nurseries closed, women found themselves trying to juggle yet more responsibilities at home.2

This habit of accessing news while doing other things would explain why in many of the countries surveyed women are more likely to use TV and radio while men use print and magazines.

Men and women experience social media very differently. Part of this is behavioural. A study by Facebook3 of users in the United States shows that women on their platform tend to share more personal issues (e.g. family matters, relationships), whereas men discuss more abstract topics (e.g. politics).

But this is only a very small part of the story. Men and women interact differently with news, partly through personal choices and partly in response to the way they are treated when they do venture into public debates. Marjan Nadim and Audun Fladmoe (2019) looked at whether women experience more and different online harassment to men in Norway, a country with high levels of gender equality and a well-funded independent media system.

Their findings show that, while men often receive more comments directed at their opinions and attitudes, women who come under attack are likely to change their behaviours and become more wary of expressing opinions publicly. And while men tended to be attacked for what they think, i.e. their arguments and political attitudes, women are attacked more for simply being women.

Pew Research on online abuse in the United States shows a similar pattern: women are about twice as likely as men to say they have been targeted as a result of their gender, while men are more likely to be attacked for their political views.4 Women also encounter sexualised forms of abuse at much higher rates than men, and some 21% of women aged 18 to 29 report being sexually harassed online, a figure that is more than double the share for men in the same age group. The overall tone of online harassment towards women relies on hyperbole and sexualised language, along with more subtle suggestions that women are somehow lesser, undeserving of resources, and less capable than men (Jane 2017).

This online environment may well explain differences in how women engage with news, and how they comment and share news with their networks. Our data from the Digital News Report 2020 (Newman et al. 2020) also highlight how women in many countries rely on a trusted friend or relative, or their partner, to tell them the news, passing on the snippets they feel may be interesting or relevant to them.

They also tended to engage with news via their networks. In the next chapter we show that women discuss news with people they know, face to face. Among the countries covered here, this is especially true in Kenya, where they rely on friends and family rather than news editors to curate their news consumption.

It worth spending some time looking at just where women do build communities and share, and where they are likely to feel comfortable in the company of others in their network. While men are more likely to be counted as news lovers in most countries, women are still likely to spend vast amounts of time consuming news and information, but on different sites, often ones linked to their caring responsibilities.

In many countries a portion of some women’s time is spent on other forums, often ones based on parenting, that still play a significant role in how women consume news. While not all women are parents, many still join these sites to participate in a female chat forum.5 As a result many women consume news – occasionally through links to the original article but frequently through summaries and the ensuing debates. Mumsnet in particular has become the site of and target of ferocious commentary over feminism and trans rights.

A Pew Center research from 2015 on parents and social media explores how parents – 75% of whom use social media – turn to social media for parenting-related information and social support in the US.6 And there are several parenting websites, Babyworld in the US, Mumsnet in the UK, for example, that provide this service and that parents use to fill an information gap.

A study in the UK focused on the parents of children with mental health needs showed that, in the absence of enough provision of child and adolescent mental health services, parents are seeking alternative forms of support and information from these sites (Croucher et al. 2020). Women use similar forums for other matters, such as dealing with children with cystic fibrosis or parents with dementia.

Many of the reasons cited for using these forums – to manage emotions and identity, and to seek a sense of belonging and relevant, actionable information – are also things many newsrooms are hoping to tap into with their membership models, newsletters, and verticals. Indeed, many of the more successful subscription models have come from news organisations, such as Helsingin Sanomat in Finland, that have recognised that many readers are more willing to pay for this kind of information and community building than they are for politics and general news.

Trust in news is a multi-faceted concept and a quick glance at our data shows that women and men are almost equally likely to trust or distrust news in most of the countries we analyse. But it is worth looking at patterns in how people share news, and how much they trust the news they receive through social media, through private messaging apps from their close friends and family. As Nikolaus Jackob (2012) points out in a study of German attitudes towards trust, it was found that there are positive correlations between interpersonal trust, trust in the media, and trust in other institutions.

Wealth and education matter in this area too. Hannah Hagen, in her study on trust in media in the Americas (2019), argues that a person’s level of education is the strongest sociodemographic predictor of trust in media, with men and women with lower levels of education trusting news more than those with higher levels of education. Levels of wealth also affect trust in media, with higher levels of wealth predicting less trust.

Some studies report that women are on average more trusting than men, possibly putting more faith in interpersonal relations, but our data show no consistent difference in levels of trust between men and women in the countries surveyed. There are some differences between how much men and women trust media they see on social media and the news they receive through their personal networks, but overall, the trends in trust in news move in the same direction for both genders.

In this chapter, we carry out a descriptive analysis using the Digital News Report 2020 (Newman et al. 2020) survey data collected in 2020 to identify key gender differences and similarities in news and media use in 11 markets: Kenya, South Africa, South Korea, Hong Kong, Japan, Mexico, Brazil, Finland, Germany, United Kingdom, and United States.

Some of the differences identified may reflect other factors than gender, and all will be shaped by other factors in addition to gender, but news and media use is in part gendered behaviour and it is as important to document and recognise differences between how women and men use news and media.

Below, we first present the methodology of the Digital News Report. Then, we address interest in news and present findings from both 2020 and 2017 Digital News Report data, what sources of news women rely on, patterns around trust in news, and levels of concern over false or misleading information. We conclude by summarising the main findings.

The Digital News Report survey is carried out to understand how news is being consumed in 40 markets. The survey is commissioned by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism and carried out by YouGov. The 2020 report investigates the impact of coronavirus on news consumption as well as other topics such as trust and misinformation, local news, paying for news. As the Digital News Report deals with news consumption, all those survey participants who stated that they had not accessed any news in the past month were excluded from the data. The surveys were conducted with online samples. Therefore, these samples may underrepresent the news habits of respondents who are older, less affluent, and with lower levels of education. This is particularly important to remember when interpreting results from countries with lower levels of internet penetration. In this report, those countries are Brazil, Mexico, South Africa, and Kenya. Furthermore, answers rely on ‘recalling’, which may be subject to biases or often be imperfect. To minimise the effect of such biases, we carefully designed and tested our questions.7 Finally, the figures presented in this analysis represent descriptive results. Therefore, small differences between female and male populations that we report in this chapter might not be significant and should be interpreted with caution. Table 1 presents the number of women and men in each market.8

Table 1

News consumption may be influenced by a variety of factors, including interest in the news. Individuals may be interested in different types of news, for example, ‘hard or soft news’, and thus may consume news that appeals to such interests. How interested are women in news? To answer, we analyse the gender breakdown of responses to the following question, ‘How interested, if at all, would you say you are in news?’ and compare the percentages of women and men who say they are ‘extremely’ or ‘very’ interested (Figure 1).

Across all 11 markets, men are more likely to say they are interested in news than women, and in most countries covered the difference between men and women is ten percentage points or more. Men are also more likely to say that they are interested in local news than women. However, the level of interest for both gender groups in local news seems to be lower than news in general. Furthermore, interest in local news increases with age: both men and women over 35 are more likely to say they are interested in local news than those under 35.

Figure 1

But top-line responses to a single, general question about interest risk obscuring a more nuanced picture, for example a situation where women and men are equally interested in the substance that news covers, but not equally interested in most news coverage they come across, or where women and men are interested in different kinds of news and news coverage of different topics. In fact, closer analysis of data from the 2017 Digital News Report, which included a more detailed set of questions around interest in different topics, suggests women are more interested in some topics even while they do express less interest in, for example, political news. The survey that year did not include South Africa and Kenya, so we cannot report from these countries, but in the rest of the markets, we observe some differences between female and male news consumers in terms of the subject of news they say they are interested in.

Men are more likely than women to say that they are ‘extremely’ or ‘very’ interested in political news across all markets, again with differences between men and women of ten percentage points or more in most countries (see Figure 2). Women, however, are more likely than men to express high levels of interest in news about health and education (see Figure 3). There is little difference in both gender groups’ interest in news about justice, crime, and security but, as the following chapter will show, men and women feel very differently about the way female victims of crime and assault are covered by the media. However, differences in interest in political news might be due to differences in how these news stories are presented, rather than differences in interest in political news as a whole.

Figure 2

Figure 3

When asked about their primary source of news, in most markets, women are more likely than men to report that they use TV news programmes or bulletins, but in a handful of markets there are no clear gender differences (Figure 4). None of the 11 markets covered have a significantly larger number of men relying on TV news.

When asked about how they access news, women in most markets are less likely than men to report visiting news sites ‘directly’ (Figure 5). Further, female respondents are slightly more likely to say that they come across news on social media in most markets, and are less likely to report that they access news via aggregators in the majority of markets.

Facebook remains the most popular social media site for both men and women regarding news consumption – e.g. Mexico (70%) Kenya (66%), and Hong Kong (58%) – in most markets.9 Two other important social media sites, YouTube and Twitter, are less popular in terms of news use among women than among men. Figures 6 and 7 show the gender breakdown of all those who reported using Twitter and YouTube as a news source, respectively.

While the percentage of those who use Twitter for news remains relatively low, we find that, on average, women are less likely than men to report using Twitter for news in most markets. The same is true for YouTube as a news source in most markets.

Figure 6

Figure 7

We observe some differences between men and women regarding how they participate in online discussions over news stories. First, while the differences between the two groups are small in most markets, we find that women are generally slightly less likely than men to report (1) commenting on news stories on news sites and (2) commenting on news stories on social media.

Second, in half of the markets, women are more likely than men to say they prefer talking about a news story face to face with their friends or colleagues. For instance, Figure 8 presents the gender breakdown of ‘commenting on a news story on news sites’. In the US, while 18% of male respondents say they comment on news stories, only 11% of women do the same. Figure 9 presents the percentage of those who say they prefer to ‘talk face-to-face to friends or colleagues’ about a news story. Across all markets, women report that they like to discuss news face to face with people they know well. (For both figures, the difference in several markets is small enough that it should be treated with caution, given the sample size and reliance on recall.)

Figure 8

Figure 9

Our data show that men and women may consume and access news differently, but there are not many differences in how much they trust it. When asked if they agree or disagree with the following statement: ‘I think I can trust most news most of the time’, we observe no systematic significant variation between men and women (Figure 10). (The only exception is Finland, where 60% of women say that they trust most news most of the time, compared to 52% of male respondents doing the same.) Similarly, we find only small and mostly not significant variation in terms of how many men and women respectively say they trust news in social media.

Figure 10

While the level of concern over fake news seems to be high across most of the markets, in South Korea, Japan, and Finland, we find that women are slightly more likely than men to say they are concerned over what is fake or real on the internet (Figure 11). Hong Kong is the only market where significantly more men say they are concerned about this.

Figure 11

Similarly, when we look more closely at levels of concerns for different possible sources and platforms for online misinformation we find no systematic significant differences by gender.

Online survey data from the 11 markets we study show that female news consumers are less likely than male news consumers to report being ‘extremely’ or ‘very’ interested in news in general. When looking at specific topics, women express more interest in news about health and education, while men are more likely to say they are interested in political news. While women are not as likely as men to say they are interested in news, they still access it frequently, especially via television and social media. In terms of engaging with news, women are more likely to say they discuss news offline, but less likely to say they comment on news online on news sites or social media.

We find no major differences between women and men regarding trust in news in general and trust in news on social media. For both men and women, Facebook remains the most popular social media site for news in most markets, while Twitter and YouTube are less popular ways of accessing news among women than among men. Finally, we find that women and men are equally concerned about false or misleading information online.

The results we present here are only descriptive. Therefore it is essential to avoid any causal references. However, some of our findings, such as interest in news, show clear differences between female and male news consumers. Further comparative and longitudinal investigations would advance our understanding of how women consume and engage with news.

Kenya | South Africa | South Korea | Hong Kong | Japan | Mexico | Brazil | Finland | Germany | United Kingdom | United States

Data over news consumption tell only part of the of how women consume news. These country profiles, written by local researchers and journalists, aim to give a broader picture of the main debates around women and news. The profiles also address the issue of gender diversity in the newsroom, and highlight some news products that aim to serve women audiences in new ways.

By Verah Okeyo and Meera Selva

Kenyan women’s anger over the country’s high rates of domestic violence, femicide, and the media portrayal of victims as somehow complicit in their own deaths has sparked a nationwide conversation about the role of women in newsrooms.

Some recent high-profile murders have acted as lightning rods for the protests: in 2018 a university student, Sharon Otieno, was raped and murdered. She was having an affair with a senior politician who was investigated over her death and much of the domestic media used the case as a hook for writing articles about sugar daddies and female students. And the following year, when a medical student, Ivy Wangechi, was murdered by a man who was stalking her, the media spent a disproportionate amount of time on the motivations of her killer.

A series of social media movements including the Twitter hashtag #TotalShutdownKe and the Counting the Dead project (which keeps a tally of femicide victims) sprang up and coalesced around the Women’s Day demonstrations. This year, attention also turned to the dangers posed to women living with abusive partners during lockdown.

Newsrooms in Kenya are still dominated by men at the higher levels, and while there have been a handful of senior newspaper editors who are women, Kenyan female journalists have tended to cover the more traditional beats of health, science, and lifestyle.10

This has meant the news agenda has been decided by men and women have been portrayed under the male gaze. There is a new generation of female investigative and political reporters who are building up impressive reputations but they frequently find themselves the target of online attacks.11

Two respected female news anchors, Lulu Hassan and Kanze Dena, were subjected to an absurd level of trolling in 2017 after they interviewed the president Uhuru Kenyatta in a wide-ranging interview that included a few soft questions about football and how he spends his free time. The comments focused on how they were asking silly questions, and were unsuited for political interviews, even though the resulting programme was a hit in terms of ratings with both men and women.12

There are some initiatives to serve women audiences, but they tend to be external: the BBC has partnered with many media stations in Africa to create She Word, and The Nation, one of the country’s main newspapers, has a donor-funded gender desk. These initiatives have created space for news aimed at women, often by women, but they are generally seen as separate from the main news desk and their existence has little impact on the wider culture of Kenyan newsrooms.

By Chris Roper and Amanda Strydom

South Africans might feel proud of their country’s rankings in the 2020 Reuters Institute Women and Leadership in the News Media report (Andı et al. 2020). Of 163 editors at 200 brands around the world, the report finds 23% are women. South Africa is the outlier: 47% of top media positions are held by women, far ahead of leaders in gender parity like Finland and Germany. Furthermore, in an analysis of online news users in each market who say they get their news from an outlet where a woman is in charge, Japan comes in last at 0%, and South Africa is first at 77%.

The numbers may be impressive, but the celebration is short-lived: ‘looking more broadly at gender inequality in society and the percentage of women in top editorial positions’, the report concludes, ‘we find no meaningful correlation’. In other words: the state of representation in top jobs proves an unreliable indicator of gender equality elsewhere in society. As the report finds: ‘Journalism clearly has its own, internal, dynamics influencing career paths and the gender composition of top editorial ranks.’

South Africa provides us with a fresh perspective on issues of equality: despite massive problems of gender inequality – exacerbated by South Africa’s grotesquely high GINI coefficient and extraordinary levels of gender-based violence – there is a disproportionately high percentage of women in top editorial positions. This anomaly is not restricted to the media, but extends into government. In 2019, for the first time in its history, South Africa achieved gender parity in its cabinet.

And yet South Africa ranks low by almost every other gender equality measure, but women there won’t need numbers to verify what they already know to be true: South Africa is a terrible place to be a woman. Of course, one could argue that one of the reasons for this awareness (besides lived experience) is that the media do actively make a point of covering issues of gender-based violence. But, again, this doesn’t extend to overall gender parity in the share of news voice. The most recent research from the Global Media Monitoring Research Project (2015, and due to be updated for 2020) showed women only appear in 29% of media coverage. For a more recent statistic, an analysis of coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic by the organisation Media Monitoring Africa revealed that 80% of those quoted in stories about the virus were men.

Steps are being taken to address these issues. For example, the same organisation has just started a project called Lens on Gender, which will monitor media to get an overview of how they have been reporting gender-based violence before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, and to establish the presence of women’s voices in media coverage. The Lens on Gender project will not only advocate for better coverage in terms of portrayal, but will also call and fight for the equal representation of women in media coverage in terms of voice.

Another organisation, Quote This Woman+, runs a database of women experts across a number of sectors as a resource for journalists to expand their sources.

As with much of the rest of the world, one of the key issues for women in media is the level of online aggression directed against women journalists. In South Africa, this is compounded by a generalised attack on the media, to varying degrees, by all the major political parties. The most egregious offenders are the Economic Freedom Fighters, a populist party that has both made and encouraged threats of violence against women journalists specifically. There are a multitude of examples of this.

For example, the EFF’s leader Julius Malema published a journalist’s mobile number on Twitter, with accompanying text accusing her of attempting to spy on the party. This led to threats of rape and death, and a subsequent court case in which the party was ordered to pay costs, and delete the tweet. Perhaps predictably, this led to further attacks on the journalist on social media.

A cursory online search would reveal many other examples of targeted social media attacks. This aggression has led to physical violence against journalists. A recent example was eNCA journalist Nobesuthu Hejana being harassed and chased away by EFF members as she attempted to cover a protest in September 2020. The EFF’s response to the outcry against this included a tweet by Member of Parliament Mbuyiseni Ndlozi, stating that ‘merely touching her is not harassment. The touch has to be violent, invasive or harmful to become harassment.’

By Ahran Park

The #MeToo movement has had a significant impact on the discourse around violence against women in South Korea and the stigma that had been attached to victims of assault. This changed significantly after 2018, largely due to media coverage of the global movement. Women in the arts, academia, politics, and film and entertainment industries spoke about their experiences, and the media in South Korea created an environment that eventually emboldened women to speak out against politicians who had harassed them.

In one of the most high-profile cases, a former governor of Chungcheongnam-do was found guilty of sexually assaulting his secretary and sentenced to prison for three years and six months in 2019.

The media coverage and public interest in the case marked a sea change in attitudes but also led to a discussion over salacious or insensitive reporting of assault. Young women in particular were upset by the tone of some of the stories, especially those around the reporting of the death by suicide of a pop singer following the release of an explicit video filmed by a former boyfriend. Indeed, the Digital News Report 2020: South Korea (Park and Lee 2020) found Korean women in their twenties had the lowest news trust among all ages and genders. The country’s strict defamation laws have been used to stymie reporting on sexual assault, with both victims and journalists coming under attack.

Female journalists in South Korea still face an uphill battle for parity. The Korea Press Foundation survey of 1,956 Korean journalists in 2019 showed that the ratio of female reporters is relatively low: women comprised 26.3% of newspaper journalists, 19.6% of TV reporters, and 37.7% of online newspaper reporters. Also, only 31.4% of female reporters were married while 71.3% of male reporters were. These data imply that journalism is seen as incompatible with married life for many women, and this is borne out by the fact that there are very few women at the higher levels of media organisations.

There is some change. In November 2019, for the first time in broadcasting history, KBS (Korea Broadcasting System) appointed a female reporter, Lee Sojeong, as the main news anchor for the prime-time news, reversing the format of a senior older male journalist paired with a younger female colleague. But there is still a way to go.

According to the Korean Woman Journalists Association, there were only four female board members out of 115 executive positions at major news companies in 2019. Women and Leadership in the News Media 2020 also shows the percentage of female top editors in South Korea was recorded at 11%, as against an average of 23% in the ten countries surveyed.

By Grace Leung and Meera Selva

Hong Kong’s year of upheaval has seen fundamental questions raised about the role of journalists, and the portrayal of civilians and authorities by the media. Women have been front and centre of the protests, and have taken to the streets in Hong Kong in equal numbers to men this year in protest against the Mainland-backed extradition bill. #ProtestToo highlighted the inappropriate full body searches and humiliations several female protestors complain they have endured at the hands of the authorities.13

A survey of journalists covering the protests showed that, while both male and female journalists were likely to come under physical and online attack, women were much more likely to be insulted on their age and appearance. They were also more likely to receive rape threats, threats against their family, or to be labelled prostitutes (Luqiu 2020).

Women are going into journalism in significant numbers, and in many newsrooms outnumber their male colleagues. They are still slightly less likely to reach the higher level: data from the Hong Kong Journalists Association shows 28.7% of their male members are working at the senior and middle levels in news organisations, while the percentage for female members is slightly lower at 24.8%.14 The real difference comes not in levels of seniority but in the way beats are allocated: men still dominate breaking news and sports, while lifestyle and cultural news will be mainly covered by women. And on television news channels, the typical pairing of an older, senior male journalist with a younger, more junior and attractive female still pervades.

The portrayal of women in the media became the subject of significant discussion in 2008, when explicit photographs of the pop star and actor Edison Chen and various female partners (many of them celebrities in their own right) were leaked. Amid the furore over privacy on the internet, many female journalists became uneasy about their newsrooms’ decisions to put the images of naked women on the front pages (So 2008). The Hong Kong Economic Times was one of the few that decided not to publish the images, a decision made by their female news editor and one that highlighted the importance of women in senior roles.

By Yasuomi Sawa

Japan’s legacy media have audience figures that other countries can only dream of, including national daily newspapers with circulations in the millions, and loyal viewers for public broadcaster NHK and several commercial TV networks. But those audiences and the media brands that serve them still skew overwhelmingly male, particularly conservative legacy brands. Consider Nikkei, which purchased the Financial Times in 2015: it has 60% male readership in print and 71% male users online.

The people featured in news stories are also overwhelmingly masculine in Japan: 77% in print and 80% on TV.15 The number gets steeper when you filter for politics and government news: 96% of contributors are men.16 This reflects a tendency for traditional news outlets to cover people from government and official authorities, where men still dominate, rather than from grassroots movements and civil societies, where many Japanese women often play more major roles than men.

Japan’s newsrooms also have a long way to go to reach gender parity. An industry-wide survey17 of gender balance in newsrooms showed only 22.4% of newspaper journalists and 25.3% of journalists in Tokyo’s major broadcasters are women. Women occupy 8.5% of management positions in newspapers and 15.1% in broadcast stations. No woman sits as a top editor in TV or print in Tokyo: the only woman with the title of managing editor in a major newspaper in Japan is Kazue Yonamine of Okinawa Tim.

Some companies have begun to experiment with new formats and casting policies to change this. One such outlet is Abema TV, a four-year-old multi-channel streaming TV service launched jointly by online media company Cyberagent and major commercial broadcaster TV Asahi. It has developed debate programmes that deal with topics like sexual harassment in the workplace, sexually emphasised girls in anime and manga, or questioning the policy of mandatory heels for female workers (this inspired a local spinoff movement called #KuToo named after kutsu, which means ‘shoes’ as well as ‘agony’ in Japanese).

Although the content is only a small part of TV Asahi’s output, it has gained a reputation for controversy in the way it gives a platform to people from across the political spectrum, from human rights activists to conservative populist commentators.

The country’s dominant messenger app LINE is another platform worth mentioning: among those who say they get their news on the app, 64% are women, as opposed to 47% on Twitter and 40% on YouTube.

By María Elena Gutiérrez Rentería and Juliana Fregoso

The gender pay gap, intra-family violence, and a growing resistance to the long-held Latin American tradition of social machismo have all dominated public debate in Mexico in recent years. A fast-growing protest movement against gender-based violence has remained active this year despite the pandemic, organising demonstrations and marches and social media campaigns against gender-based violence.

For the women involved in the protests, the media are seen as part of the problem. When 25-year-old Ingrid Escamilla was violently killed by her partner, several media outlets and digital news sites published a leaked image of her mutilated body. Women’s groups reacted with fury to what they claimed was dehumanising and salacious coverage of her murder, and began social media campaigns posting images of landscapes and flowers in her name to try to ensure that an online search for her name would not call up the gruesome images of her corpse.

But the movement has also sustained a journalism focused on covering women’s issues from a female perspective. Cimac, a crowd-funded and foundation-backed site with news on health and human rights, is one of the best established, but other smaller local sites are also growing.

The assassination of investigative journalist Maria Elena Ferral Hernández in March 2020 was a stark reminder too that Mexico is one of the most dangerous places in the world to be a journalist, and that women journalists investigating corruption and organised crime are as much under threat as their male colleagues.18 While Mexico ranks relatively low in the number of female editors at leading publications,19 there are many examples of excellent female editorial leadership, including Adela Navarro who heads Zeta, a publication based in Tijuan, and has championed investigative journalism – often at great personal risk.

By Rodrigo Carro

Brazilians have elected (and re-elected) a female president in the past decade, but the country lags behind other Latin American nations when it comes to true political parity: only 9% of government ministers and 15% of parliamentarians are women, according to the UNDP’s Atenea Project.20

But while political representation of women’s interests may be lacking in the halls of power, their political will has never been more visible on the streets: 2.9 million women were mobilised in the #EleNão (Not Him) protests around the election of Jair Bolsonaro. There has also been more space in Brazilian mainstream media to discuss hot-button women’s issues, including reproductive rights and LGBT identity.

Recent years have seen the emergence of new women’s media that are not skewed heavily towards fashion and beauty content. In 2018, top-ranking Brazilian website Universo Online (UOL) launched Universa, with the motto ‘your world is the world’. Its content ranges widely between questions of race and sex, to multiple uses for apple cider vinegar and conversations on mansplaining.

In 2019, O Globo joined UOL with the launch of Celina: a website that promises to help women stay ‘on top of discussions about diversity and inclusion’. The content is kept mostly online, but sometimes strays into O Globo’s print edition. The name of the site was chosen as a tribute to the teacher Celina Guimarães Viana, the first woman to vote in Brazil. Last year, the site launched an online database of all female experts, with more than a hundred specialists in different areas to help reporters consult more female contributors.

But while these two new ventures offer hope, there is still much room to improve the news coverage of femicide and sexual violence in Brazil. A 2019 survey by Instituto Patrícia Galvão analysed 1,583 stories about the murder of women and 478 about rape published between 2015 and 2016, in 71 different media outlets. One of the main conclusions was that media outlets failed to humanise the victims adequately, sometimes even blaming them for what happened.

The debate about abortion rights, even in cases in which the Brazilian laws permit terminations, remains highly polarised. A 2019 opinion poll by Instituto Datafolha showed that 41% of the population was against abortion in any circumstance. A recent case that drew huge attention in the press involved a pregnant 10-year-old rape victim who was denied an abortion at a hospital in her home state even after a local court authorised the procedure. The child was made to travel over 900 miles to another state to get the procedure done. Brazil’s minister for Women, Family and Human Rights, Damares Alves, publicly criticised the abortion and argued that the child should have undergone a Caesarean.

Reporting of stories like these often falls to male reporters in Brazil, where women only fill 41.8% of available positions, according to a 2018 survey.21 That’s despite them making up more than half of the country’s population. The divide is even starker in radio newsrooms and studios, where men outnumber women three to one.

Another study, based on interviews with 477 female journalists from 271 different media outlets, found almost 40% of the respondents felt that being a woman had reduced their chances of being promoted. The research, carried out by Abraji in 2017, also found 65.4% of respondents worked in an organisation where there were more men than women in leadership positions.22

These less-than-favourable conditions have not stopped women from reaching the top: the country’s leading financial paper, Valor Econômico, has been run by female editor-in-chief Vera Brandimarte since 2003. Furthermore, two of her four executive editors are women. In O Globo, the second best-selling Brazilian paper as of June 2020, 40% of the main editors were women, as well as half of the executive editors.

By Jenni Kangasniemi

This Nordic country has long been considered a pioneer in gender equality, and journalism has been a female-dominated field in Finland since the 1990s. That said, the top power positions in society are still largely held by men, and women remain underrepresented in coverage.

The country has a long tradition of monitoring women’s media representation. The country’s leading daily newspaper Helsingin Sanomat, for instance, has adopted a 50:50 mission, aiming to feature women and men equally on its pages, with a gender equality tracker bot: software which keeps track of how many women have been mentioned in its stories. For a long time, the proportion of women has been hovering around 30%. Yet Helsingin Sanomat is not alone in its struggle. A similar pattern is repeated in other media outlets.

These numbers partly reflect reality, including the fact that the Finnish labour market is still strongly gender-divided. However, societal structures are only one side of the coin. Journalism not only reflects inequality but also creates it. Even though society is becoming more equal, this doesn’t automatically translate into more women in headlines.

Gender monitoring has had at least one favourable effect in making the journalistic traditions and processes in newsrooms more transparent. The simple act of numerical monitoring is only a starting point but indeed a useful one. It has already opened doors for more fine-tuned discussion on equality. In the end, the most crucial questions are qualitative, not quantitative. What roles do women take in news? How do we speak to female audiences?

In the aftermath of the #MeToo movement, women’s safety, both offline and online, has become another national topic of discussion. And 2018 marked the first year that the National Crime Victimisation Survey looked separately at online harassment. According to the findings, women face harassment more often than men, and the same pattern holds true online. In Finland, women are more hesitant to engage in discussion around news online, and fear may very well play a role.

The year 2020 has been transformative for gender equality. At the end of 2019, Finland formed a government of five parties, all led by women. The shift from a more male-dominated governance marked a historical moment which made news all over the world. It sparked a discussion not only on women’s roles in society, but also on the role of the media in representing women. As the nation woke up to the new reality of female state leaders on front pages every day, the journalistic traditions of representing women were exposed. So, when a Finnish tabloid dubbed the new coalition a ‘sewing circle’ and asked the government to ‘look up from their handiwork’, it sparked a heated debate. Do the media treat women fairly?

The debate intensified when in October 2020 Finland’s prime minister Sanna Marin appeared in the women’s magazine Trendi, sporting a blazer with a plunging neckline. In the article, Marin spoke to the readers with a more personal tone, sharing views on the pressures that a millennial woman faces in Finland.

The audience reactions perfectly showcase the contrasting attitudes towards women and the media. The defenders of Marin posted pictures of themselves in similar outfits accompanied with the hashtag #imwithsanna, congratulating the prime minister for amplifying women’s voices. The detractors, however, accused Marin of publicly shaming herself. Some criticised her for wearing a low-cut blazer, others for ‘wasting time’ in a women’s magazine instead of a political publication.

This reaction raised important questions. If a male politician were to give a similar interview, would he be ridiculed or celebrated? The criticism also exposed the hierarchy of ‘male’ and ‘female’ journalism that still exists. Lifestyle journalism and other female-oriented content still carry negative connotations of being superficial fluff – not fit for a politician. Even though Finnish women read more than men on average, more men report being interested in news. By this they usually mean the traditional hard news genres, such as politics and economy.

However, old hierarchies are slowly shifting. As Finland’s media market has started to move online, there has been a growing demand for women-specific content on multiple platforms. Female-oriented TV channels such as Liv have been able to establish a loyal following. Recently, Finland’s biggest podcast platform, Supla, started creating more content for its female followers in the male-dominated podcast market. Popular women’s magazines such as Me Naiset and Anna have managed to build an active online community.

At the end of 2019, Finland’s leading media company Sanoma merged five lifestyle magazine brands into Helsingin Sanomat. The newspaper had a solid lifestyle content strategy before, but with help of the new brands, it is able to focus on lifestyle topics even more.

The merging of lifestyle and news has managed to attract a significant number of new paying subscribers. This includes both men and women, as well as young subscribers who express more dissatisfaction with traditional news than any other reader segment. The integration has also proved that topics that have historically been more female-oriented are indeed newsworthy. At the same time, the need to categorise news into male and female genres has been questioned.

Interestingly, two opposing trends are emerging simultaneously: on the one hand, women’s perspectives are seen as special and worth amplifying; on the other hand, there is a push towards journalism where gender doesn’t matter. As recent developments in the Finnish media landscape have shown, both views can coexist in harmony.

By Julia Behre and Sascha Hölig

Even in a wealthy and democratic society like Germany, there are several difficulties when it comes to the relationship between women and the news. We can observe striking gender inequalities in both news consumption and production that must be seen in the context of broader social and political structures.

German data from this year’s Reuters Institute Digital News Report reveal several findings: women show less interest in politics and in the news and access it less frequently than men. These gender gaps in news consumption are even higher in the younger generation aged 18 to 24 years. Men in this age range are twice as likely to identify themselves as extremely interested in the news as their female counterparts.

Moreover, young women are much more likely to use social media as their main source of news. This is a worrying finding, since these individuals often come across news in social media unintentionally (Fletcher and Nielsen 2020b) and hold a ‘news finds me’ perception, which is also associated with lower political interest and knowledge (Gil de Zúñiga and Diehl 2019).

Although the promotion of diversity is a key function of public service broadcasting, only Berlin-Brandenburg public broadcaster (RBB) has an equal gender distribution in its leading positions (von Garmissen and Biresch 2018). In Germany’s leading print media, the share of women in executive positions ranges from 15% to 52%, with news magazine Stern heading the ranking (ProQuote Medien 2020). Women are underrepresented not only in media institutions, but also in news coverage. About one-third of all German politicians covered in the most relevant German TV news shows in 2018 were women, even though the German chancellor is female (Krüger and Zapf-Schramm 2019). A content analysis of German TV news dealing with COVID-19 (Prommer and Stüwe 2020) also reveals that only one in five of experts consulted on issues related to the crisis were female. It is little wonder then that traditional German news might have difficulties in meeting the specific interests of women.

The emergence of Instagram as a preferred news source among young women deserves closer attention. Instagram facilitates positive self-expression, self-disclosure, and social support in an entirely new way (Schaffer and Debb 2020) and may provide a more positive, personal, and sensitive news environment that is more appealing to girls and young women. A lot of digital-born news brands have harnessed Instagram to target teenagers and young adults with stories on feminism, sexuality, social injustice, health, and sustainability. Auf Klo (‘On the loo’) and the Instagram channel Mädelsabende (‘Girls’ nights’), both part of the public broadcasting online-platform Funk, the Instagram channel Die News-WG (‘The news flat share’) from Bavarian public broadcaster (BR), and ze.tt from the weekly newspaper Die Zeit are all popular.

By Caithlin Mercer

It’s been an exciting year for ceiling-shattering leadership appointments in the UK media industry. The Financial Times kicked off 2020 with Roula Khalaf at the helm after she was named Lionel Barber’s successor in November 2019. She is the first female editor in the paper’s 131-year history. Outgoing editor Barber told the New York Times:

You mustn’t see this as some kind of ‘woke’ gesture – it’s got nothing to do with that. She is one of our most outstanding journalists. She’s been deputy editor for four years, she’s been tested in all sorts of areas, and that’s why she’s the next editor.23

The same can be said of other appointments of highly skilled women in 2020. At News UK, Emma Tucker became the first female editor of the Sunday Times since 1901, and Victoria Newton took up editorship of the Sun. The appointment of Emily Sheffield as editor of the Evening Standard in July took the tally of national papers helmed by women to 36%. In digital media, Jess Brammar was named Executive Editor of HuffPost UK in February 2020 – she was seven months pregnant at the time. And rising star Izin Akhabau was appointed online editor at The Voice. In other media, former Stylist editor Georgina Holt was named Managing Director at ACast.

New media outlets like Black Ballad and Gal-dem, staffed by and written for audiences not traditionally served by legacy media, are also more likely to have women in senior roles and it has also been encouraging to see traditional outlets with broad reach like FT and HuffPost teaming up with these new outlets.24

The BBC’s 50:50 Equality Project,25 launched in 2018 with the goal of achieving an equal share of male and female contributor voices, has been an important and much copied initiative that has shone a spotlight on the issue of women’s representation in the media. It asks news teams within the BBC to simply track the number of men and women featured on its programmes, and to strive for an equal mix of the two. In March 2020, it found that two-thirds of the teams that had joined the initiative from the beginning had managed to hit that goal.

Other news organisations have begun to collect similar data. The Financial Times Janetbot26 tracks the number of images of women compared to men on its homepages and sends the data to the relevant editors through the day, to enable them to make real-time alterations. Similar tools also track the number of women quoted in news stories and featured in opinion pages.

But the progress being made in women’s representation has been seriously undermined by the dominance of men in the British government’s public response to COVID-19. An analysis27 of the UK government’s daily press briefings by Southampton University politics lecturer, Dr Jessica C. Smith, between 16 March and 10 May showed only 7% were led by a female politician (Home Secretary Priti Patel), and 44.4% included no female expert.

And a study of women’s representation in COVID-19 coverage in the UK, US, and Australia showed that only one-third of those quoted in articles about the pandemic were women, and for every mention of a female politician there were five mentions of a male politician.28

By Joy Jenkins

In the year 2020, women in America marked a significant centenary: on 18 August 1920, Tennessee became the last state needed to ratify the 19th Amendment, also known as the Susan B. Anthony Amendment, which guaranteed women the right to vote. It would be another 40 years before the right was extended to Black women, when the Voting Rights Act was passed in 1965 to eliminate the poll taxes, literacy tests, violence, and other tactics aiming to keep African Americans from voting.

Inspired by the 19th Amendment, a news organisation emerged this year to address the continued challenges faced by women and other marginalised groups in the US political arena. Led by a team of women editors and a racially, ideologically, and socioeconomically diverse newsroom, The 19th* is a ‘non profit, non partisan newsroom reporting on gender, politics and policy’ promising in-depth coverage of the 2020 election, the Supreme Court, concerns facing the LGBTQ+ community, healthcare, and systemic racism.

The launch of The 19th* led to a flurry of news coverage, with outlets calling it ‘revolutionary’ and highlighting its goal29 to be the ‘best, most diverse newsroom in America that covers gender and politics unlike any other outlet’.30 Indeed, an outlet created and led by women is revolutionary in a media environment where women editors remain rare.

The 2019 Status of Women in US Media31 reported that women comprise 41.7% and people of colour only 22.6% of the overall workforce in newsrooms. The country’s most widely distributed newspapers, sports desks, and radio news are also dominated by male and white journalists and editors, despite the fact that female students outnumber male students in college and university journalism programmes. Additionally, according to the Status of Women in US Media, in some of the country’s most prominent newsrooms, including the New York Times, Associated Press, Los Angeles Times, and Washington Post, women earn substantially less than their male colleagues.

The lack of diversity among newsroom leadership is reflected in the news, where sourcing practices, particularly in coverage32 of politics, the economy, and celebrities and sports, favour men. Women experts are also lacking in coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic, with white male experts dominating reports on epidemiological models, herd immunity, the virus’s spread, and its impact on those infected, according to a Nieman Lab report.33 This trend is likely to continue, as research34 has shown that, across scientific disciplines, women are publishing less and starting fewer projects than their male colleagues.

Despite producing some of the country’s best journalism (five women won Pulitzer Prizes this year, and 13 were finalists), women reporters often face harassment, assault, arrests, and mistreatment. In 2020, women have been arrested covering an anti-eviction protest in Oregon and the arrest of a protestor in Los Angeles,35 and have endured police attacks, civilian attacks, harassment, arrests, and detentions covering the protests in response to the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis in May. New York Times reporter Kathy Gray said she was escorted out of a campaign rally in Michigan for President Donald Trump after posting on social media about the lack of mask wearing and social distancing among the crowd.

To combat some of the dangers that women journalists encounter, a visual journalist and editor at the University of Missouri this year launched an app called JSafe, which allows users to report an incident, along with photos, videos, and a location. If they mark the incident as ‘urgent’, the Coalition of Women in Journalism responds with resources and advice; the Coalition also uses the app to track Twitter and Facebook accounts accused of abuse.

In addition to the 19th*, other news outlets have emerged to address issues important to women and spotlight the work of women journalists. These outlets are particularly important at a time when people encounter news via social media and mobile alerts, and some citizens avoid it altogether36 (younger people and women systematically avoid news more frequently).

While many women’s magazines37 and feminist blogs, such as Feministing, The Toast, The Hairpin, and Jezebel, are struggling,38 mainstream outlets have introduced women-centric products, including In Her Words at the New York Times, a newsletter on women, gender, and society, and the Washington Post’s The Lily, a vertical aimed at millennial women. Women-run podcasts and networks, such as My Favorite Murder, Hear to Slay, and The Morning Toast, are also growing in popularity. These trends bode well for both women media creators and consumers, offering outlets for telling their stories and reaching broad and engaged audiences.

This report has sought to raise some of the major themes concerning women and news and identify some gaps that need to be filled. Gathering data on the problem is an important first step. The BBC’s 50:50 project that counts the number of women featured on news programmes, and software such as the Financial Times JanetBot and the Helsingin Sanomat gender bot provide real time data on women’s representation in the media.39

These datasets, working in tandem with gendered databases such as Quote This Woman+ in South Africa which make it easier for journalists to find female sources, can help increase women’s representation in the media. But they only work if they are properly resourced, and if they have the backing of senior editors and buy-in from key journalists within the organisation.

In a year when media organisations worldwide have seen job cuts and sharp falls in revenue (Nielsen et al. 2020a), these tools may seem like a luxury newsrooms cannot afford. But it is precisely at this moment that gender diversity should come to the fore, to reach the women who have been disproportionately hit by the pandemic.

A new media ecosystem that recognises how women are affected by structural inequalities in wider societies through different levels of financial autonomy, restricted access to the labour market, and lesser political representation can both reach new audiences and find new narratives.

The country profiles in this report show how women often feel let down by media coverage of domestic violence and femicide. Social media provide some opportunities for mobilisation, community building, and the creation of new narratives as a counterweight, but it is also an arena for gendered attacks, where women can face trolling, rape threats, and personal attacks.

These gendered attacks are also frequently used against women journalists, and are part of a wider trend where individuals and even people in positions of authority encourage their supporters to harass journalists online, with the explicit aim of discrediting their work.40

Ultimately, achieving gender parity in the news media, both for audiences and for content creators, requires a fundamental shift in power and reset of the news agenda. The country profiles highlight several high-profile appointments of women to leading media organisations, but overall women are still underrepresented at the top of the industry. A true rebalance involves promoting more women to senior roles and again ensuring they have the resources and support needed to implement their visions and not simply act as caretakers for existing ways of reporting the news.

We end on an upbeat note, with the results of a workshop carried out with an female group of journalist fellows from four different continents, at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism in November 2020.

The day ended with a wishlist: if the women in the room could design their ideal news product, what would it look like? The answer was news that was gender-aware, with a new power structure that gave women spaces at all levels of decision-making in the newsroom and in public life. They wanted women’s news that was agenda-setting, where issues that impacted women hardest were centred and a key part of the public discourse. And in terms of format, they wanted it to be mobile, visual, interactive, shareable, and conversational, with a civil online space for comment and discussion.

In other words, what women want is the news industry of the future. We are already operating in an environment where news is moving to mobile and to platforms. A newsroom that harnesses these changes also understands the need to change the culture of the newsroom to better reflect the needs of their audience.

This tallies with Lucy Kueng’s (2020) observations in her book on newsroom cultures: any media business model that requires financial and personal commitment from a reader must address the issue of diversity head on.

To grow subscriber numbers (a more pressing goal since the decline in classic advertising revenues has accelerated), newsrooms need to attract different readers in different segments and by extension this means different people in the newsroom: if everyone looks the same, thinks the same, and has similar backgrounds, they are likely to produce the same kind of content for the same type of audiences.

Women are the great untapped audience for certain types of news. This report has highlighted how women are less likely to consider themselves very interested in political news, but more likely to be interested in health and education.

This year has shown that health and education policies are at the heart of politics and misreading the public mood over both can undermine the legitimacy of governments. It is vital for the future of journalism and the future of democratic participation that women are given equal space both inside the newsroom and inside stories, to help keep the media industry relevant to people’s lives. If news media are unwilling to deliver this, they cannot pretend to be surprised when many women turn their backs on them.

1 From insights to action: Gender equality in the wake of COVID-19, UN Women

2 From insights to action: Gender equality in the wake of COVID-19, UN Women

3 Gender-Specific Behaviors on Social Media and What They Mean for Online Communications, Social Media Today; Gender, Topic, and Audience Response: An Analysis of User-Generated Content on Facebook

4 Online Harassment 2017, Pew Research Center

5 Mumsnet in the UK says 9% of its users do not have children.

6 Parents and social media, Pew Research Center

7 For the methodology see Digital News Report 2020

8 We used the unweighted number of respondents (women and men) presented in Table 1 in all figures except Figures 2 and 3, where we used data from Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2017. Sample sizes regarding Figures 2 and 3 are provided in their respective captions.

9 The only exceptions to the popularity of Facebook usage for news are Japan (6%) and South Korea (19%).

10 Online safety for women journalists, Amwik

11 The Gender Agenda, Media Council of Kenya

12 Online safety for women journalists, Amwik

13 ‘Women at Forefront of Hong Kong’s Anti-Government Movement’, South China Morning Post.

14 The figures were provided by Miss Helena Mak, the General Secretary of the Hong Kong Journalist Association on 15 Oct. 2020 via WhatsApp message.

15 Shimbun Roren (Japan Federation of Newspaper Workers Union), ‘The Result of Survey: Women in Management Position in Media’.

16 Who Makes the News? Global Media Monitoring Project 2015.

17 ’Nikkei Online’s Paid Subscriber Tops 700,000: Led by 20s and Women’.

18 'Reprobamos las agresiones contra mujeres periodistas en el Estado de México y exigimos a las autoridades garantizar la labor periodística'

19 Mexico ranks 8th out of 10 markets surveyed for female leadership trends by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (Andı et al. 2020) in Mar. 2020

20 ‘Crossing Waves and Counter Waves’ 2020, ATENEA.

21 ‘O Perfil do Jornalista Brasileiro em 2018’. Survey run by media-tech Comunique-se and content production firm Apex Conteúdo Estratégico.

22 ‘Mulheres no Jornalismo Brasileiro’. Survey conducted in 2017 by the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalism (Abraji) and the independent news website Gênero e Número.

23 'Financial Times Names First Woman as Top Editor in Its 131 Years', New York Times

26 'JanetBot: Analysing gender diversity on the FT homepage' Financial Times

27 'Where Are the Women? Descriptive Representation and COVID-19 in

U.K. Daily Press Briefings' Politics & Gender

28 'Women have been marginalised in Covid-19 media coverage,' Kings College London

29 'The Newsroom Where Politics Is Not About Men' The Cut; 'The 19th: A Revolutionary Non-Partisan News Site For Women, Made By Women', Forbes

30 'The Newsroom Where Politics Is Not About Men', The Cut

31 'The Status of Women in U.S. Media 2019', Women's Media Center

32 'Who makes the news?,' Global Media Monitoring Project 2015

33 'In COVID-19 coverage, female experts are missing' Nieman Lab

34 'Are women publishing less during the pandemic? Here’s what the data say'

35 'UNITED STATES: KPCC REPORTER JOSIE HUANG ARRESTED WITH BRUTAL TREATMENT WHILE WHILE COVERING SHOOTING OF LOS ANGELES SHERIFF’S DEPUTIES IN CRITICAL CONDITION', The Coalition for Women in Journalism

36 'What makes people avoid the news? Trust, age, political leanings — but also whether their country’s press is free', Nieman Lab

37 'Women’s magazines are dying. Will we miss them when they’re gone', Washington Post

38 'A Farewell to Feministing and the Heyday of Feminist Blogging', New York Times

39 'JanetBot: Analysing gender diversity on the FT homepage' Financial Times

40 'Online harassment of journalists: the trolls attack', Reporters Without Borders

Meera Selva is director of the Journalist Fellowship Programme at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism and an accomplished senior journalist with experience in Europe, Asia, and Africa. She spent three years working in Berlin and Singapore for Handelsblatt, and had previously spent several years as a UK correspondent for the Associated Press. She has also worked out of Nairobi as Africa correspondent for the Independent and as a business journalist at a range of publications, including the Daily Telegraph and Citywire.

Simge Andı is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. She works on the Digital News Project, and uses survey and experimental data to study the consumption and sharing of online news. She holds a PhD in Political Science and International Relations.

Thank you to all the journalist fellows at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism for their input and insights into this project. Thanks also to Rasmus Kleis Nielsen and Richard Fletcher for guidance and advice over the Digital News Report data, and to Alex Reid for getting this over the line. This report was made possible with funding from the New Venture Fund.

Published by the Reuters Insitute for the Study of Journalism.

This report can be reproduced under the Creative Commons licence CC BY. For more information please go to this link.