Jump to section: Introduction | Methodology | Definitions and typology | Five key findings | Conclusions | References

DOI: 10.60625/risj-44pf-1k13

Introduction ↑

News creators and influencers operating in social and video networks have become a significant source of news in recent years. Our own Reuters Institute Digital News Report indicates that personalities and news creators often eclipse traditional news brands in terms of attention when using certain social and video networks (Newman et al. 2023, 2024, 2025). Pew Research finds that around a fifth (21%) of adults in the United States (US) and more than a third of Under-30s (37%) now regularly get news from so-called creators or influencers, with the majority of these saying that the way these personalities present the news helps them better understand current events and civic issues (Stocking et al. 2024).

Creators are also having an increasingly important political impact, with Donald Trump courting popular YouTubers and podcasters such as Joe Rogan and the Nelk Boys in the run-up to his 2024 election victory. The recent murder of activist and podcaster Charlie Kirk, and the coverage of the aftermath, reminds us of the critical role these personalities are now playing in shaping both public opinion and political narratives. In other parts of the world, politicians such as Emmanuel Macron (France),1 Anthony Albanese (Australia),2 Claudia Sheinbaum (Mexico),3 and Keir Starmer (UK)4 have also been taking notice of these trends, incorporating social media influencers into their media strategies, prioritising interviews with TikTokkers and YouTubers – as well as inviting them to government briefings. Elsewhere, in countries where press freedom is under threat or where debate in mainstream media is restricted, we have seen creators and influencers playing a different role – providing a much-needed source of critical or alternative views.

Online influencers may be attracting more attention but at least some of their content is considered unreliable by audiences (Newman et al. 2025), with well-documented cases of false or misleading information around subjects such as politics, health, and climate change raising important questions about what this might mean for our democracies.

In this report we aim to show how the trend towards online and social media news influencers is developing in 24 countries around the world. Using an audience-based approach we identify countries where influencers are having the biggest (and smallest) impact as well as some of the most important individuals. We also provide an emerging typology or categorisation of news creators, while recognising the inherent difficulties in this process given the diversity of styles, overlapping approaches, and broad range of content.

After explaining the methodology and typology, this report contains an opening section that summarises the overall findings. This is followed by 24 individual country sections where we highlight the news creators most mentioned by audiences in our Digital News Report surveys, the main networks used, and a few other characteristics of each market. The final section draws some conclusions and references other emerging work in this area.

Methodology ↑

The data for this report come from the Reuters Institute Digital News Report surveys. In the 2024 and 2025 surveys we asked respondents who said they used social or video networks for news to tell us where they paid most attention when it comes to news (news brands and journalists, news creators, etc.). We then asked respondents to name some of the news brands and individual creators that they paid most attention to using open text fields.

In this report we analyse in detail these open responses from both the 2024 and 2025 surveys, counting mentions of both individuals and news brands across the dataset to identify the most frequently mentioned in each category. We supplement these lists with desk research and consultation with country experts.

In the 2025 survey, all respondents who said they used Facebook, X, YouTube, Instagram, Snapchat, or TikTok for news in the last week were asked, for one randomly selected network they used, which sources they paid most attention to (traditional news media/journalists, digital-first news outlets not associated with traditional media, creators/personalities who mostly focus on the news, creators/personalities who occasionally focus on the news), and then, for each source type, to name up to three. In the 2024 survey, respondents were presented with a slightly different set of sources and, if they were selected, were asked to name up to three mainstream outlets or journalists, and up to three alternative news sources or online personalities or celebrities. See the Digital News Report website for the full questions.5

These questions were designed to provide enough breadth in terms of different social networks and different source types to be able to map the ecosystem and construct our typology. These data cannot be used to reliably estimate the proportion who pay attention to each individual or brand, though they can be used to highlight a selection of creators and influencers who are among the most widely encountered in each country. Moreover, surveys capture people’s self-reported behaviour, which does not always reflect people’s actual behaviour due to biases and imperfect recall.

We used open text response boxes to collect the data for several reasons. First, because in many countries the most popular news creators and influencers have not yet been identified by previous research. Second, because it would likely not be possible to fully capture the broad and fragmented nature of this ecosystem using a fixed listed of response options. And third, because we wanted to adopt an audience-centric approach whereby respondents could enter names that they considered news sources to them, even if they did not meet accepted standards or definitions within academia or the journalistic profession. This means that many of the names we list here would perhaps have been excluded under a more top-down approach.

Although open text responses enable an audience-centric approach, and research shows that they can be a more accurate way of measuring people’s news exposure (Guess 2015), they are more challenging to analyse at scale. This is because misspellings, shorthand references, low-quality responses, and other errors all have to be cleaned and recoded, and groups of responses have to be merged into meaningful categories. We used two parallel processes to clean and process the data. We applied a range of commonly used text editing and clustering algorithms using OpenRefine, and supplemented this with manual editing and checking within the software by the authors. We also used ChatGPT5 to process and recode the original data, to identify the most mentioned individuals and news brands, and to provide pen-portraits for each in English. Previous research has shown that large language models can very reliably recode open survey responses (Mellon et al. 2024) and annotate short texts across multiple languages (Heseltine and Clemm von Hohenberg 2024). Both sets of responses were manually checked against the original data, with any discrepancies resolved by the authors. We also added follower/subscriber counts on social media for each individual as a rough proxy for the size of a particular individual’s audience. We also asked country experts to review all information and provide a sense check. It is important to acknowledge, however, that this kind of analysis, even when undertaken by humans, can be subject to error and necessarily involves judgement calls. This means that, in addition to the usual error and uncertainty associated with surveys (see the Digital News Report methodology for a specific description) there is the potential for additional error in the order of the names in the lists, and on either side of the necessary cut-off point. Our lists are inclusive in terms of being faithful to the names mentioned by respondents. We removed just a handful of actors, sports stars, and celebrities if we were sure they did not post on any news-related issues.

We applied the same process in 24 countries, which were chosen to provide geographic diversity (Europe, Americas, Africa, and Asia-Pacific) as well as a good mix of different media systems. The countries chosen were United States, Canada, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, Colombia, United Kingdom, Norway, Netherlands, Germany, France, Spain, Czech Republic, Poland, Australia, India, Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand, South Korea, Japan, Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa. In order to achieve the biggest sample of names, we used data from open fields in both our 2024 and 2025 surveys, in all countries except Nigeria, Kenya, Colombia, Mexico, Indonesia, and the Philippines where data were drawn only from our 2025 survey because the questions were not asked there in 2024.

Data from India, Kenya, and Nigeria are representative of younger English speakers and not the national population, because it is not possible to reach other groups in a representative way using an online survey. The survey was fielded mostly in English in these markets, and restricted to ages 18 to 50 in Kenya and Nigeria. Findings should not be taken to be nationally representative in these countries.

Definitions and typology ↑

Social and video networks offer anyone the opportunity to build an audience off the back of free global distribution and increasingly powerful creator tools. In combination with new ways of monetising content, these attributes have encouraged a new breed of creators and an explosion of content across many genres, including news.

At the same time, traditional news organisations have been adapting their content for social and video networks, driven by increasing audience preference for consuming on these platforms. Much of this is delivered through brand-led accounts, but some publishers are also leaning into ‘personality-led’ social accounts as a way to engage younger audiences in particular.

In another recent development, some high-profile journalists have started to leave news organisations and set up on their own, either because they want more control or believe they can make more money – or both.

Politicians have also been investing time in building their own social media profiles as a way of increasing their influence and, in some cases, communicating with the public while dodging media scrutiny. And around them we find a huge number of political activists looking to amplify their talking points, as well as troll accounts (in some countries) designed to denigrate opponents.

For these reasons, and those outlined in the methodology, mapping different types of news content creators on social media is extremely challenging, but based on our analysis of around 40,000 unique named individuals we have attempted to do this in a common way across 24 countries.

The audience-derived lists that we publish later in the report contain names of a range of individuals including news creators, journalists, and politicians – because we want to understand where audiences are placing their attention on social media. However, we are particularly interested in news creators because this is the area that we believe is least understood. We also want to understand the gaps they fill that mainstream media and traditional journalists may not be serving.

By news creators we mean …

Individuals (or sometimes small groups of individuals) who create and distribute content primarily through social and video networks and have some impact on public debates around news and current affairs. News creators are independent from wider news institutions for at least some of their news output. As such, they overlap with what are sometimes referred to as ‘newsfluencers’ (Hurcombe 2024) or ‘peripheral actors’ in the academic literature (Hanusch and Löhmann 2022).

Within this group, our typology of news creators is primarily based around the content they produce, and makes a distinction between those who are focused on…

1. The News: by which we mean politics, wars, and other parts of the traditional agenda.

2. News-adjacent content: a broader definition of news often used by younger groups (Collao 2022) and includes both a wider range of subjects (entertainment, religion, gaming) as well as more diverse presentation formats including comedy, memes, and the like.

However, as we acknowledge in more detail below, in practice the dividing lines between these two categories (and their respective sub-categories) can be extremely fuzzy.

Audience-centric typology of news creators on social media

Part one: The news

In this section we identify four approaches taken by news creators and indicate the different level of challenge each poses for traditional journalism.

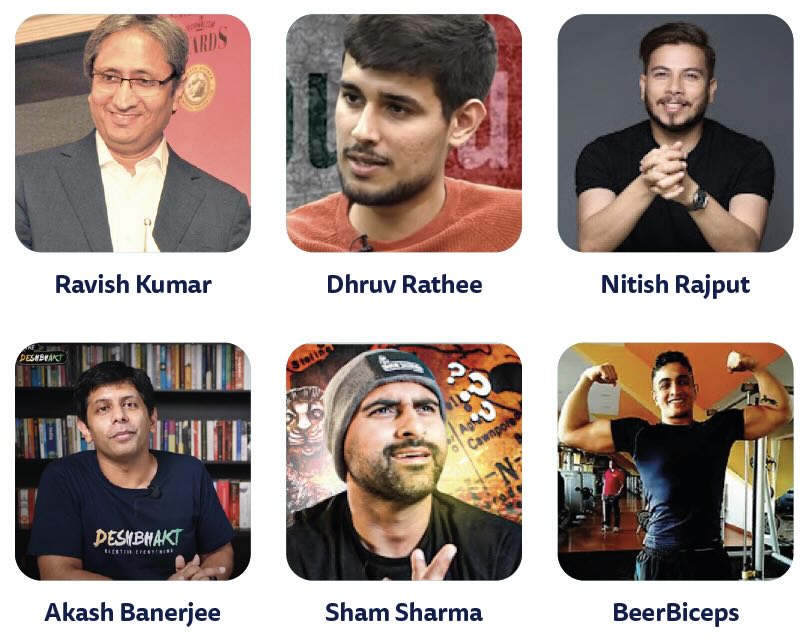

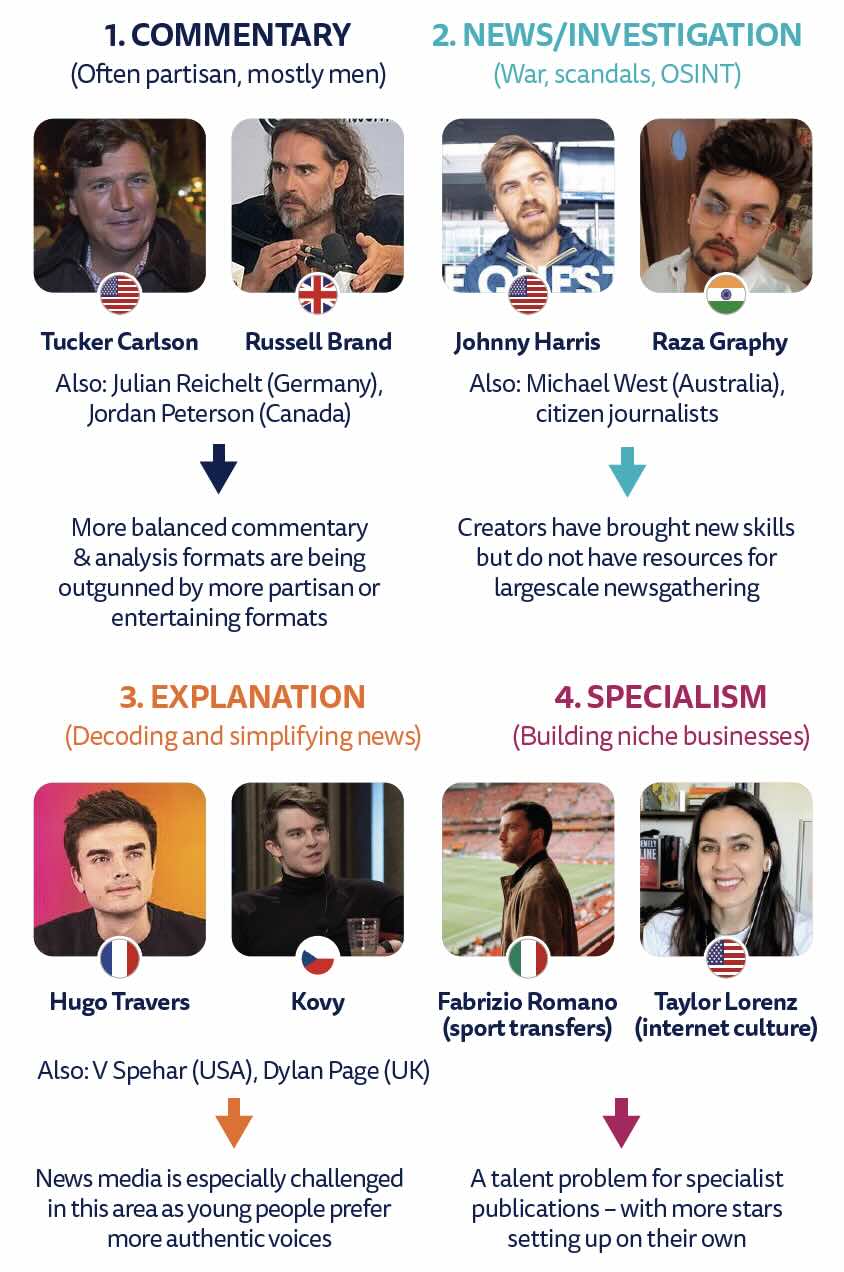

1. Commentary is the most frequently mentioned category represented in our data and generally describes online political chat show hosts (such as Tucker Carlson, Joe Rogan, and Russell Brand). Commentary tends to be cheap and does not require investment in newsgathering or infrastructure. It is also unconstrained by regulation or norms around impartiality that may exist for television and radio. The vast majority of creator-led commentary is produced by men. Many of the biggest names in political commentary such as Ravish Kumar (India), Julian Reichelt (Germany), and Piers Morgan (UK) used to work as journalists but are now highly critical of the mainstream media. They relish the freedom to express their true opinions with titles like Unplugged, Uncensored, or Unchained. In some countries (United States, Brazil, India) we find evidence that some of these shows are attracting as much attention as mainstream media talk shows – but elsewhere (Spain, Argentina, France, Norway) we tend to find that traditional publishers have more effectively harnessed social distribution, arguably strengthening the profile and bargaining power of broadcast stars. In the United States the vast majority of political commentary comes from creators who self-identify on the right and are supportive of Donald Trump. But in other countries such as India and Thailand, where debates in mainstream media tend to be more controlled, creators tend to be critical of the government.

2. News and investigation: Although less frequently mentioned, we find many examples of creators and citizen journalists who break news or conduct detailed investigations across countries. These are often on matters of great public interest that have been poorly or inconsistently covered by mainstream media. Palestinians reporting from Gaza were well represented in our lists, among them Motaz Azaiza, a former aid worker whose footage during the early stages of the conflict was widely shared. In Ukraine we have seen a consistent set of social media accounts providing detailed news about the latest fighting that has been largely absent in mainstream media. And in Kenya, citizen journalists have been documenting police brutality in recent street protests. But there are also many examples of independent long-form investigative journalism, such as Michael West in Australia (The West Report) and Johnny Harris in the United States, whose videos are rigorously researched and often take months to complete. Indian creator Raza Graphy has 3.5m followers for his YouTube channel that is dedicated to exposing fake news in India. In Japan, Brazil, Thailand, South Africa, and Kenya, among other countries, we find hugely popular creators who run accounts focused on the latest salacious crimes or break news about scandals (often about other online creators and influencers), frequently with legal consequences for the individuals concerned. Overall, this is probably the area where creators are making least impact compared with well-resourced traditional media, though networked investigators such as Bellingcat have pioneered open-source approaches to verification (OSINT/Open-Source Intelligence) that have been incorporated by mainstream media.6

3. Explanation: Across countries we find creators who explain the news in simple and accessible ways, often for younger consumers. HugoDécrypte (real name Hugo Travers) is the poster child for this type of content. Still in his twenties, he is the most mentioned French news creator or journalist in our survey and has over 7m followers on TikTok and 5m on Instagram – far more than even the biggest legacy news brands on these platforms. In addition to explaining complex news topics, he interviews politicians, including the Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky. But there are many other examples. Kovy is a young online personality from the Czech Republic known for explanatory videos about politics; Herr Anwalt is a German TikTokker with 7m followers who explains legal issues to Gen Z audiences; and husband-and-wife team Abhi and Niyu (3.5m subscribers on YouTube) produce videos that simplify and decode complex issues for young Indians. These examples reflect the popularity of new storytelling techniques designed for a generation that is faced with a huge amount of content competing for their attention and that often sees news as a chore. This category of creators is taking attention away from traditional media, which often struggle to connect with younger audiences, but arguably they are also providing societal value by helping to educate people about politics and current affairs. This group also has a more symbiotic relationship with the mainstream media – it is essentially remixing mainstream content – and is much less hostile towards such media than political commentators.

4. Specialism: Here we find individuals who work in a specific niche, often at greater depth than can be found in a traditional media organisation. Many specialists are former journalists who have left big media companies so they can devote more time to their chosen subject. Taylor Lorenz previously covered internet culture for the Washington Post but left to run her own Substack and podcast. She has been outspoken about the constraints of mainstream media and the benefits of a creator lifestyle. Fabrizio Romano is one of the best-connected sports journalists in media and regularly breaks news about football transfers. He has 25m followers on X and over 2m subscribers to his YouTube channel. In addition to former journalists, we find lawyers, academics, doctors, personal finance experts, and crypto fans building very powerful and specific communities. Specialists bring a passion to their work that is often shared by their audience, and this helps them monetise their work through subscription, membership, donation, or personal appearances.

Part two: News-adjacent creators

Here we find a broad range of creators and formats that are more fun or entertaining. Some of these rarely talk about news and politics (or do so in a humorous way), but the size of their audience, which is often larger than those in the first section, and the trust and authenticity that they have built up can still have a powerful impact on political debates.

1. Satire and comedy: In almost every country we find satirical or humorous news accounts that are popular, especially with younger audiences. Brozo is a satirical clown character (7m followers on X) known for his cynical commentary on Mexican politics. In Canada, Cody Johnston delivers comedic rants on politics to 1m followers of his Some More News show on YouTube, while The Deshbhakt, hosted by Akash Banerjee, offers satirical takes on Indian politics. In the United States, stars from late-night TV such as Steven Colbert, John Oliver, and Trevor Noah are widely mentioned – a reminder that much of this is not new; rather, it is being packaged and distributed in fresh ways. Indeed, humour and comedy are a defining feature of much creator output including explainer videos (Dave Jorgenson) and political commentary. Joe Rogan is a comedian as well as a talk show host, for example.

2. Infotainment: Some of the biggest social accounts in terms of size belong to entertainment or celebrity podcasters. Steven Bartlett’s Diary of a CEO podcast (12m subscribers on YouTube) is among the most popular in the UK. He interviews entrepreneurs and other celebrities covering topics such as business, success, and well-being. The show has been criticised for amplifying health-based misinformation.7 Alex Cooper’s Call Her Daddy (1.7m subscribers on YouTube) covers dating, sex, mental health, and personal empowerment. She welcomed presidential candidate Kamala Harris as a guest in the run-up to the November election, who was keen to access her younger female audience. MacG is co-host of South Africa’s most popular YouTube podcast and mixes entertainment with often controversial discussion of cultural and social issues.

3. Gaming and music: In most countries we find younger people paying attention to gamers and e-sports streamers on platforms such as YouTube or Twitch. Ibai is a Spanish internet celebrity streamer (20m followers on Twitch and 13m on YouTube) known for bridging digital content with mainstream culture, interviewing high-profile athletes, entertainers, and global influencers. Rezo is a German musician and podcaster (1.6m subscribers on YouTube) who mostly talks about lighter subjects but made an influential viral video about how traditional politics is failing young people. He has also spoken out against the rise of the far right in Germany.

4. Lifestyle: This category indicates how broadly many people now interpret news. Effectively it means anything that is ‘new’ or interesting to them. These areas have some of the most followed creators on the internet, especially in Brazil. Virginia Fonseca (fashion blogger) has 53m followers on Instagram and 39m on TikTok. Ria Ricis is an Indonesian influencer known for hijab tutorials and lifestyle content. She has 44m followers on YouTube and 47m on TikTok.

A few caveats on the typology and definitions

While these categories look neat, it is important to note that in practice the dividing lines are extremely fuzzy. Many creators defy categorisation. Others may start with one approach in mind (say explainer videos) but expand into other areas (investigation or commentary). This is a very fluid space, especially given how responsive creators must be to ever-shifting audience preferences and behaviours.

It is also difficult to distinguish between ‘news’ or ‘news-adjacent’ creators and a wider set of influencers that includes musicians, comedians, and sports personalities among others. In terms of our typology and country-based lists, we have included them only if they post or talk about current events but have excluded them if we can find no record of this.

A third challenge is the emergence of creator collectives or creator-led news brands that operate primarily on social media. In line with our audience-centric approach, where audiences have identified them as individuals, we have tended to categorise these as creators rather than news brands.

Finally, politicians and business people are also frequently mentioned by survey respondents in the context of news sources on social media and have significant followings (e.g. on X, Donald Trump has 109m, Narendra Modi 109m, and Elon Musk 225m). Many politicians are also content creators and commentators who shape public debates. Some content creators have become politicians, and vice versa.

For this reason, they are not part of our news creator typology, but we have included them in our lists of most mentioned individuals along with journalists who belong to mainstream media, because we think it is useful to see how each group ranks in terms of public attention.

Five key findings ↑

1. There are big differences across countries in terms of creator attention and impact

In the Digital News Report 2025, we asked social media users about the attention paid to news organisations and their journalists – as well as to different types of creators (namely, ‘those who mainly focus on news’ and ‘those that occasionally [do this]’). If we map the proportion who paid attention to each across markets, we find substantial differences between countries.

The chart below shows that there is a set of markets including Brazil, Mexico, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and the United States (as well as Nigeria, Kenya, and South Africa) where news creators are having a very significant impact. In most of these markets people also say they pay more attention to creators and influencers than to mainstream news brands (or their journalists) when using social media, as indicated by the position below the line of equality.

By contrast, in much of Northern Europe and also Japan the impact of news creators tends to be much more limited. In most of these markets traditional news brands tend to get more attention than individuals.

These differences can partly be explained by varying levels of use of social media for news, but there are likely to be other factors including cultural differences, the size of the market, and the strength or weakness of legacy media.

This interpretation is supported by analyses of the citations for individuals (news creators, other creators, and journalists) drawn from the follow-up survey question where people were asked to provide up to three names using open text responses. The chart above shows the number of mentions for individuals in different countries (based on references to individuals who were mentioned three or more times). This is another useful way to illustrate the extent to which individuals and news creators might be having a significant impact in a particular country. The data show the biggest number of mentions in Kenya, Thailand, South Africa, Nigeria, Brazil, India, the United States, and a much smaller number in Northern Europe, Australia, Canada, and Japan.

2. A few news creators stand head and shoulders above the rest

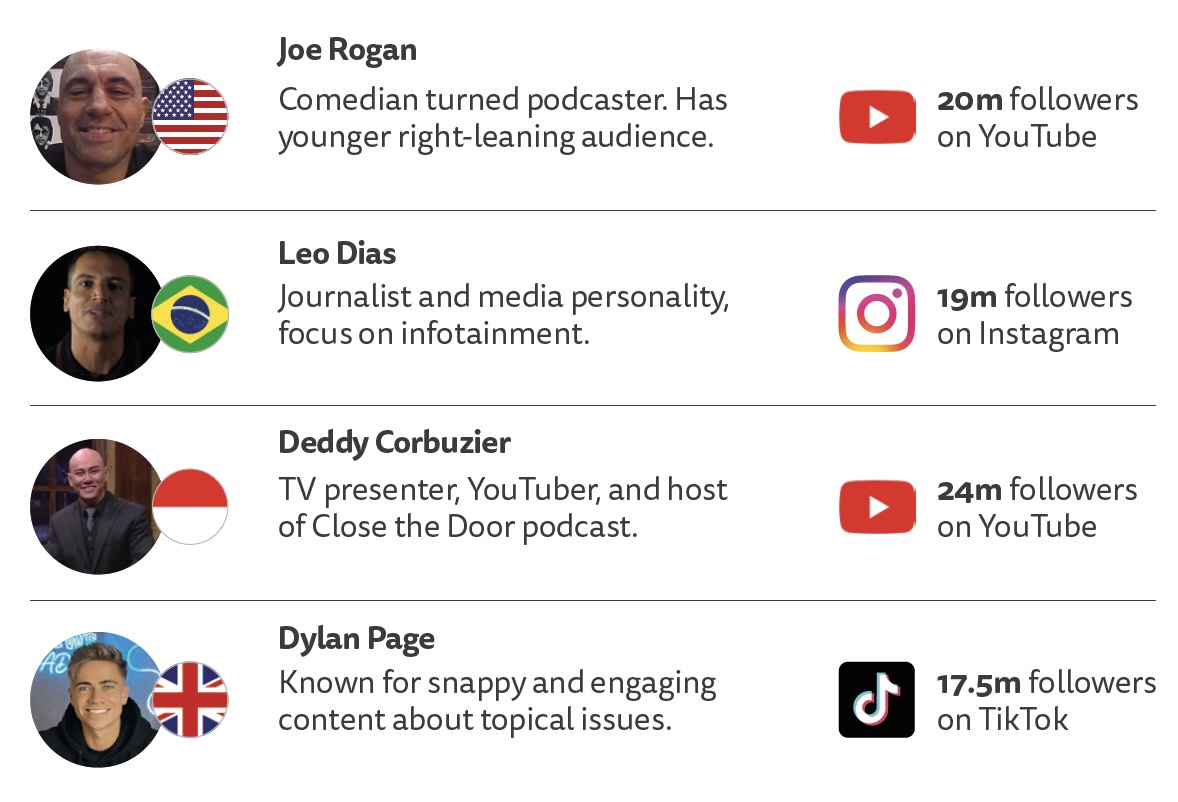

While most individuals get a handful of mentions at most, in a few countries we find personalities and news creators who are much more frequently mentioned by survey respondents. Looking at the publicly available follower counts of some of the most popular names is another indication of their wider impact.

Some of the most popular news creators reach millions of followers across platforms. These include those who provide ‘commentary’ such as Joe Rogan and Tucker Carlson in the United States, Dhruv Rathee and Ravish Kumar in India, ‘infotainers’ such as Leo Dias in Brazil, and ‘explainers’ such as Dylan Page in the UK.

But these numbers are very much the exception. The majority of news creators lie in the long tail providing regular value to a particular audience, perhaps burning brightly for a while before losing traction. In smaller countries even the top news creators struggle to reach a million subscribers on individual platforms, with average plays for videos typically in the tens of thousands.

3. Creator consumption is primarily national in nature, but there are exceptions

In most countries attention is focused on domestic creators, but many English-speaking countries show a different pattern. In particular, right-leaning political commentators from the United States, such as Joe Rogan, Tucker Carlson, and Ben Shapiro, have found fertile ground for their pro-free speech and anti-mainstream media narratives in a number of countries in this study. Two-thirds of the most mentioned list in Canada are creators/personalities based in the United States or the UK, with an even higher number seen in Australia. In some European countries where English is widely spoken (and the domestic creator space is nascent), we also find US commentators appearing regularly in the top ten lists, highlighting how politics in these countries is being impacted, to some degree at least, by the US radical right.

Elon Musk’s name is mentioned in all 24 countries, perhaps not surprising given his control of the X platform and its algorithm (225m followers). Donald Trump’s name is also widely cited across markets. We also find mentions of self-declared misogynist Andrew Tate in around half of our 24 countries, though often with very small numbers. His aspirational messages aimed at young men have proved effective in connecting with a small minority across borders.

Football transfer specialist Fabrizio Romano is mentioned by respondents in almost every country in our survey including South Africa, Kenya, Norway, and the United States. Creators are increasingly able to draw on passionate fans wherever they live.

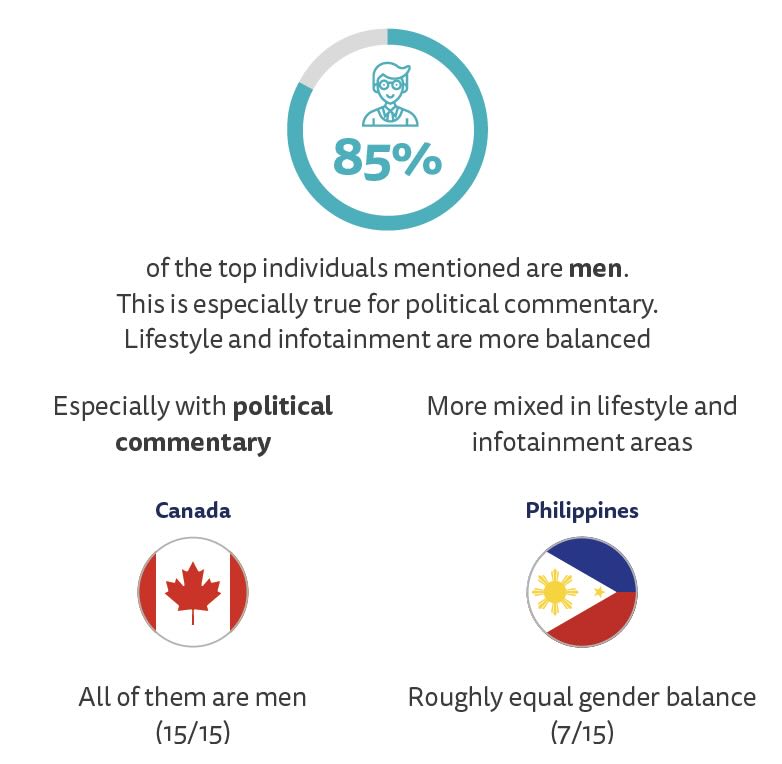

4. News creators and personalities tend to be men

In analysing the most mentioned individuals in social and video networks across 24 countries we find that the vast majority (85%) of the top 15 in each country are men. In Canada the entire top 15 list is made up of men. The Philippines has the lowest proportion of men (46%) in the top list and the highest proportion of female news creators and journalists (54%).

Political commentary is particularly prone to male-dominated presentation, with hosts often talking with other men into very large microphones. Not surprisingly audiences for this content also tend to be male (but not exclusively so).8 By contrast, a significant proportion of top lifestyle creators (e.g. Virginia Fonseca in Brazil) are women with predominantly female audiences.

In analysing the audiences that pay attention to both news creators and mainstream news brands we find that the key difference is around age. Under-35s who use social media are more likely to consume news from creators (48%) than from mainstream media (41%). Those 35 and over pay more attention to mainstream media (44%) than creators (35%).

Most frequently mentioned commentators in India tend to be men

These age differences also help to explain why in aggregate there are no significant audience differences when it comes to politics. Audiences for right-leaning creators (e.g. Tucker Carlson) who tend to be older are likely being balanced out by younger audiences who use social media more heavily and tend to identify on the left.

5. YouTube is the most important platform for news creators

While Facebook remains an important platform in general, it is video platforms such as YouTube (see chart below) as well as networks with a high proportion of younger audiences that tend to be the most important spaces for creators. The chart below from the UK shows how traditional media still tend to take a good share of attention on Facebook and X, but news creators do better elsewhere. News organisations particularly struggle to attract attention on TikTok and Instagram, networks that place a premium on short-form and visual storytelling.

We find important and surprising country differences. Facebook is still used more as a news platform in parts of Asia (Thailand, Philippines) and Africa (Kenya) and as a result many individuals have profiles there. Overall, we find that X and YouTube are the most important platforms for political commentators. YouTube, TikTok, and Instagram are often favoured by creators who explain or simplify the news, though this is largely a function of the younger audience for this type of content.

X is particularly important in the United States, South Africa, Nigeria, and Japan and is still the main platform for following politicians. Instagram is widely used for political content in Brazil and Indonesia and is also very popular in India. It is often the network of choice for lifestyle and infotainment content along with YouTube.

Explore our country-based analysis:

In this section we explore the country data in more detail. We list the names of some of the top individuals that people say they pay attention to, supplementary information about what they are known for, and how many followers they have in specific networks. We also include information about the top news brands people say they pay attention to on social media and the use of different social and video networks for news from our Digital News Report 2025. In the discussion elements, we highlight news creators who are particularly popular or noteworthy.

Americas: United States | Canada | Argentina | Brazil | Colombia | Mexico

Europe: United Kingdom | France | Netherlands | Norway | Spain | Czech Republic | Poland

Asia-Pacific: Australia | India | Indonesia | Japan | Philippines | South Korea | Thailand

Africa: Kenya | Nigeria | South Africa

Conclusions ↑

This audience-centric study, based on identifying who people are paying attention to news on social media across 24 counties, reveals how messy, fragmented, and loosely defined news sources have become for many people. Politicians and traditional media have taken their wares to an unruly information space where they compete with a rich variety of news creators focusing on commentary, investigation, explainers, and niche specialisms, as well as infotainment and lifestyle creators, who frequently get drawn into political and cultural debates, either because they want to or because their audience demands it. As all this is thrown into the algorithm(s), it makes for a bewildering cocktail, but one that is also richly creative, entertaining, and informative – even if much of that information cannot always be taken on trust.

News creators, and the forces that are driving them, continue to develop at a rapid pace, but this study of more than 40,000 individual names suggests that the impact today varies considerably across countries.

We find that there is set of populous countries, generally where traditional media are under pressure and social media use is high (e.g. Thailand, India, Indonesia, Brazil, Kenya, and the United States), where news creators are having a significant impact and where a few individuals are reaching a significant number of people. At the other end of the spectrum, we find countries with strong brands and lower use of social media (mostly in northern and western Europe) where successful news creators are the exception rather than the rule.

Another general observation is that even though the internet is global, most news creators operate in a national context, due to constraints around language but also cultural and subject relevance. This is the case in Eastern Europe, most of Asia and Latin America, and parts of Africa. The major exception is in English-speaking countries where political ideas from the United States, fronted by partisan and mostly right-leaning commentators, are striking a chord with audiences in Australia, Canada, South Africa, and the United Kingdom. While those US personalities still feature heavily in our top lists in those countries, the numbers are relatively small and we could expect to see local commentators filling that space over time.

Representation is another important issue in the creator space, with our data showing that male perspectives tend to dominate – especially in the field of political commentary. Putting together our top lists of individuals across countries we find that 85% are men. In most countries we also find that right-leaning commentators heavily outnumber left-leaning ones overall, but also that in politically polarised countries audiences are often exposed mainly to creators that align with their own views.

In terms of the platform mix, we find that political commentators tend to gravitate to X and YouTube while investigators, explanatory, and news-adjacent creators tend to focus more on Instagram and TikTok (as well as YouTube). This is partly due to the younger demographics that are interested in a broader set of content and more video-led storytelling. Again, our country pages show that there are many exceptions to this rule, with Instagram widely used for political commentary in India, Indonesia, and Latin America and Facebook still a key network in the Philippines and Thailand.

What are the implications for journalism and society?

The rapid growth of news (and news-adjacent) creators is providing an extra source of competition for pressured mainstream media companies, especially with Gen Z and millennial audiences that are already reluctant to go to news websites and apps.9 In general, creators have been more adept than media companies in moulding their storytelling and their tone to the requirements of social platforms. They have also mostly proved better at attracting and keeping attention in fast-changing, algorithmically driven space. Finally, they have embraced a broader set of audience needs around entertainment, lifestyle, specialist, and passion-based content – needs that the mainstream media have largely ignored.

In considering our typology of commentary, investigation, explanation, and specialism, the level of challenge and potential opportunities can be thought of differently, as outlined in the table below.

In terms of political commentary, our data suggest that algorithmically driven platforms are pushing both creators and audiences towards more sensational and partisan approaches. Many media companies (e.g. cable TV in the United States, upmarket newspapers all over the world) largely trade in political coverage, which is why the popularity of online commentators can be seen as such a threat. In response some media companies are looking to compete on partisanship, and others such as the Washington Post are looking to collaborate with creators by bringing content (labelled) into their platform. The main concern here is over the potential impact on trust. A recent FT Strategies report, which interviewed a number of different news creators, found that many did not accept traditional journalistic norms around objectivity and impartiality, which would make such collaborations challenging, especially around news or politics.10

When it comes to investigation and original newsgathering, we find that the number of creators is relatively low. There are honourable exceptions such as open-source investigators and fact-checkers, but many of these are relatively closely aligned to existing journalistic standards such as fairness and accuracy. There is very little money to be made from committed newsgathering and longer investigations, which is why competition from creators is likely to be low.

Explanatory creators are proving popular with younger audiences and in this respect provide a useful function in educating audiences that might otherwise miss out on regular news. Because they rely on and remix traditional sources, they are less interested in criticising or undermining the news media. Because of the difficulty of sustaining this output and making money over time, many creators have built mini- brands and multiple revenue streams.

Specialism is becoming a central strategy for many news organisations looking to create more distinctive content. Legacy print newspapers have invested heavily in newsletters and podcasts that provide detailed coverage of a particular area because they have the potential to attract paid subscriptions and drive revenue from events. But independent creators are now operating in the same space with a lower cost base, leading to a talent exodus for many news organisations. Columnist Paul Krugman recently left the New York Times and now operates on Substack. Taylor Lorenz, who writes on internet culture, left the Washington Post and writes a newsletter and hosts a weekly podcast. In this area ex-journalists join academics, lawyers, footballers, musicians, and many others for whom content creation is just one part of their portfolio.

Finally, in the news-adjacent informational lifestyle area, we find a similar battle for talent and attention emerging, with podcasts and live streaming taking attention away from entertainment-based broadcast shows news. The demise of late-night TV audiences from shows like The Late Show with Stephen Colbert in the United States is part of this trend.

The future of news creators

This report provides a snapshot of activity by news creators and other personalities on social media at a particular moment in time. It’s a world that is noisy, hard to define, and changing rapidly. It has big stars, a long tail, and much in between. But where is it heading?

One of the biggest challenges for individual news creators is burnout, driven by the pressure to keep audiences engaged and the algorithm on your side. Being a creator is a popular ambition for many young people, but few are making significant amounts of money. Starting things is often fun, but keeping them going can be a grind.

That’s why a number of creators highlighted in this report are turning themselves into mini-businesses and brands. Hugo Travers is now editor-in-chief of the HugoDécrypte brand and employs over 20 staff to support his work. Johnny Harris is building a creator-driven media business by launching a network of independent YouTube channels through his company New Press. The Tucker Carlson Network (TCN) is effectively a mini media company with professional management at the back end. Dave Jorgenson, once the Washington Post’s TikTok guy, is launching a company specialising in short-form video (LNI) together with former colleagues from the Washington Post.

Meanwhile, a number of news organisations (Le Monde, Die Zeit) have been hiring young creators to run their social video content. Others are setting up creator studios focused on talent-led projects. The Independent (UK) is partnering with digital creators including high-profile football content from Adam Clery (ACFC). Vox has signed deals to help monetise the work of high-profile creators Kara Swisher, Scott Galloway, and others. At the same time, long-established digital-born brands such as PoliticsJOE and Brut continue to develop new talent and formats.

The professional and creator worlds are converging, and that is likely to mean more discussion about the need for regulation, standards, training, and other approaches to build trust and maximise commercial opportunities. These are outside the scope of this report but are starting to be discussed elsewhere.11 We’re still at the beginning of this shift to online creator-led media, and how it plays out will at least partly depend on the role platforms play in promoting valuable and useful content, the further development of business models to support these creators, and the continued interest of audiences around the world.

Footnotes

1 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3Z6HnUJ3hcw

2 https://theconversation.com/politicians-are-podcasting-their-way-onto-phone-screens-but-the-impact-may-be-fleeting-250793

3 https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/nacion/sheinbaum-promovera-que-haya-youtubers-afines-a-la-4t-la-comentocracia-se-carga-en-contra-del-gobierno-dice/

4 https://www.tiktok.com/@maxklymenko/video/7521435111821282582

5 Although slightly different questions were used in 2024 and 2025, we believe the data are broadly comparable and, given that the primary purpose is to map this space, that the added depth from two years’ worth of data outweighs any comparability issues.

7 https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c4gpz163vg2o

8 Audiences for Joe Rogan and Tucker Carlson are twice as likely to be male (Digital News Report 2025).

9 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2018–2025.

10 https://news-sustainability-project.com/decks/News%20Sustainability%20News%20Creators%20Project.pdf

11 FT Strategies; News Creators Project August 2025 https://news-sustainability-project.com/decks/News%20Sustainability%20News%20Creators%20Project.pdf

References ↑

-

Collao, K. 2022. The Kaleidoscope: Young People’s Relationship with News. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

-

Newman, N., Ross Arguedas, A., Robertson C. T., Nielsen, R. K., Fletcher, R. 2025. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2025. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

-

Newman, N., Fletcher, R, Robertson C. T., Ross Arguedas, A., Nielsen, R. K., . 2024. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2024. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

-

Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Eddy, K., Robertson C. T., Nielsen, R. K. 2023. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2023. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

-

Guess, A. M. 2015. ‘Measure for Measure: An Experimental Test of Online Political Media Exposure’, Political Analysis, 23(1), 59–75.

-

Hanusch, F., Löhmann, K. 2022. ‘Dimensions of Peripherality in Journalism: A Typology for Studying New Actors in the Journalistic Field’, Digital Journalism, 11(7), 1292–1310.

-

Heseltine, M., Clemm von Hohenberg, B. 2024. ‘Large Language Models as a Substitute for Human Experts in Annotating Political Text’, Research & Politics, 11(1).

-

Hurcombe, E. 2024. ‘Conceptualising the “Newsfluencer”: Intersecting Trajectories in Online Content Creation and Platformatised Journalism’, Digital Journalism, 1–12.

-

Mellon, J., Bailey, J., Scott, R., Breckwoldt, J., Miori, M., & Schmedeman, P. (2024). ‘Do AIs Know what the Most Important Issue is? Using Language Models to Code Open-Text Social Survey Responses at Scale’, Research & Politics, 11(1).

-

Stocking, G., Wang, L., Lipka, M., Matsa, K. E., Widjaya, R., Tomasik, E., Liedke, J. (2024, November 18). America’s News Influencers: The Creators and Consumers in the World of News and Information on Social Media. Pew Research Center.

Published by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. The data for this report comes from the Reuters Institute Digital News Report survey, which was collected with the support of the Google News Initiative (GNI).

This report can be reproduced under the Creative Commons licence CC BY.