As publishers look to reduce their dependence on platforms, many are increasingly looking at ways to build more direct and meaningful relationships with audiences. Mobile alerts, which are closely linked to their news websites and apps, have proved to be one of the most effective ways of doing this, with weekly usage of news notifications having tripled in many countries over the last decade. Publishers say that news alerts drive habit, which in turn increases brand loyalty, and ultimately propensity to pay for news.

Our podcast on the findings

Spotify | Apple Podcasts | Transcript

But at the same time, many consumers say they are becoming overwhelmed by mobile notifications of all kinds – from news aggregators as well as publishers – as well as sports scores, calendar requests, messaging groups, and social media interactions. Faced with this challenge, the companies behind mobile operating systems such as iOS and Android have started to summarise and prioritise notifications– often using AI – but this in turn threatens to reduce the direct link between news publishers and audiences. In this chapter we explore consumer attitudes to news alerts across eight countries representing different media systems.1 What kinds of people engage or disengage with these notifications and why? Which brands are benefiting most and how can publishers strike a balance between keeping users updated without unduly irritating or distracting them?

Usage of mobile news alerts

Mobile news alerts have grown significantly over the last decade, alongside our increasing reliance on smartphones and apps. Weekly use of alerts in the United States, for example, has grown from 6% to 23% since 2014 and from 3% to 18% in the UK. But most of this growth happened before 2017 and has slowed considerably as the battle for attention on the lockscreen has intensified. In some countries (such as Germany) we find that usage is relatively flat. At the same time, there is even higher use of mobile-related alerts in many parts of the Global South where smartphones are the dominant access point to the internet.

Alerts remain just one of many gateways to news

In terms of consumer usage, gateways such as search (45% weekly use) and social media (43%) are much more important in terms of overall numbers – and for attracting new users from a publisher perspective – but much of the resulting traffic often leads to shallow engagement. By contrast, notifications, along with email newsletters, are two of the mechanisms that publishers use to drive a deeper connection with existing users. Notifications are features of app software design that remind people of the value of the service and aim to increase frequency of direct usage while reducing dependence on big platforms.

Across countries around a fifth (21%) say they use news alerts weekly as a starting point for their news journey, with one in ten (9%) saying this is their main gateway.

Given that alerts are focused on existing users, it is not surprising to find that those receiving news alerts tend to be disproportionately drawn from those with high interest in the news and greater frequency of use (a group we define as ‘news lovers’) compared to more casual users. This is because access requires people, in most cases, to be interested enough to download a specific news app in the first place and give permission for notifications to be sent. Exceptions to this come with pre-installed apps such as Apple and Google News where news alerts are often part of the set-up on a new phone. In this way, some platform-driven alerts have a better chance of reaching audiences with lower interest in news and lower levels of education.

Mobile news alerts work well across all age groups and genders, whereas email newsletters, which have also proved very effective for many publishers in building loyalty, tend to perform much better with older groups.

Which brands are most frequently mentioned when it comes to mobile alerts?

In our survey we asked respondents which news organisations – or aggregators – they most often received alerts from. In general, we find that news brands that are well trusted and have a reputation for breaking news perform best. In many countries these are brands with a broadcast legacy, especially public broadcasters.

BBC News has the most widely installed news app2 in the United Kingdom and the brand was mentioned by almost half (46%) of those respondents who get news alerts, around three times as many as second-placed Sky News. This is the equivalent of around 4% of the adult population, suggesting that almost 4 million people in the UK will be notified every time the BBC sends an alert, which would make it one of the most powerful digital channels in its armoury.

Aggregators Google and Apple also play a significant role in the UK market, with many respondents complaining that this can lead to them getting multiple alerts on the same subject.

In the United States we find a more fragmented landscape, with broadcast brands CNN and Fox News near the top of the list along with the New York Times, but it is striking to see how more of the alerts come from aggregator or platform brands. In addition to Google and Apple News, Yahoo! retains a strong position in the US, while Newsbreak is a relatively new app that has aggressively used personalised alerts to drive growth. Many respondents stressed the convenience of how the news now ‘comes to them’ in a timely way, supplementing existing usage patterns:

In Germany, usage is split across multiple news brands, headed by 24-hour-news channel n-tv. Public broadcaster ARD’s Tagesschau brand also performs strongly with its alerts package. In Japan we find a different picture again with aggregators such as Yahoo! News, Line, and Smart News collectively reaching a significant proportion of those receiving notifications. This reflects the weak online position of most traditional news organisations (and their apps) in a market where access is dominated by platform aggregators. The only exception is the earthquake and tsunami disaster notification service run by public broadcaster NHK, which is installed on many people’s phones, as well as NHK’s own news app.

Aggregators also play a much bigger role in Africa where the mobile internet tends to dominate. In Kenya, Opera News, a popular AI-driven personalised app not related to the Opera browser, is a major player, while digital-born outlet Tuko.co.ke heads the list along with legacy news outlet Citizen and titles from the Nation Media Group. Kenyans also get regular news alerts from social and video networks such as Facebook, X, and YouTube, which are widely used for news more generally. Opera News is an important aggregator in South Africa too, but brands with a reputation for breaking news such as News 24 and eNCA also perform strongly.

Finally, we can look at two large markets, Brazil and India, where we also find a significant proportion of alerts being generated from tech platforms such as Google, Facebook, YouTube, and Instagram. This reflects the heavy use of platform-based consumption in these countries with algorithms generating automated alerts based on previous usage of particular subjects.

In Brazil, major web portals such as G1 (Globo), UOL, and R7 have also built a reputation for breaking news, with alerts billed as a key reason to download their apps. In India, The Times of India, NDTV, and BBC News are some of the most widely used services along with popular mobile aggregator apps such as InShorts and Daily Hunt.

Too many alerts can put people off

While mobile alerts are a good way of keeping audiences up-to-date they are not universally loved. The vast majority of our survey respondents (79% in aggregate) say they do not currently get any news alerts during an average week. This could be because they are not sufficiently interested in downloading a news app in the first place or because they have actively turned off alerts because they found them too annoying or distracting.

Across countries, more than four in ten (43%) of those that do not get alerts say they actively disabled them – either because they feel they get too many or because they are not useful: ‘They annoyed me so I turned them off’, says one respondent, while others were more concerned about the depressing nature of the news itself. ‘I turned off all my news apps and sites after Trump was elected’, says one liberal respondent from the United States, while another added ‘I have switched off notifications again because it’s emotionally distressing’. There is a clear link here with more general news avoidance trends – with those who say they ‘often avoid’ the news less likely to sign up in the first place and more likely to disable them later.

But it’s not just about overload. Respondents also found alerts could be frustrating in other ways: ‘Sometimes the headlines are misleading when you select the article. Sometimes you have to pay to view the content especially on Apple News’, says one UK respondent (M, 42).

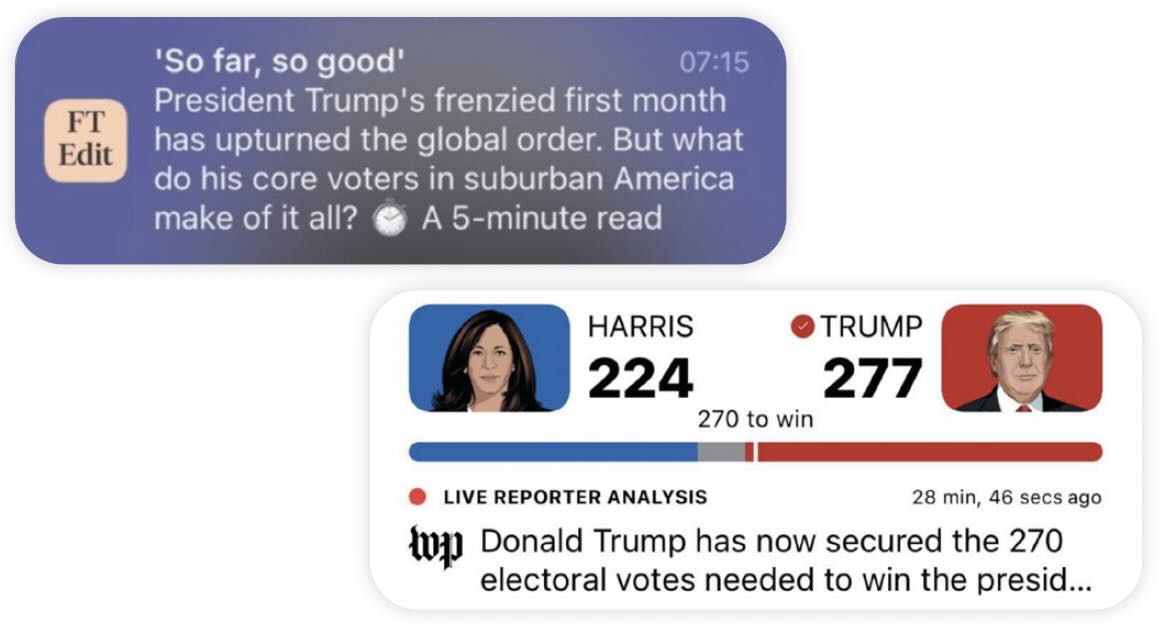

Publishers are extremely conscious of the tightrope they are walking when sending news alerts. Most have strict limits on the number they send each day and clear criteria about the type of alerts as well as the best time to send them. The Times of London, for example, sends no more than four each day, conscious that more frequent alerts can lead to a spike of those uninstalling the app. The Financial Times sends a number of general news alerts to all and then for those that opt in, a personalised notification at around 5:00 pm each day based on a subscriber’s particular interests, as well as a morning briefing alert. At the weekend there is promotion of longer reads and relaxed features.

Some alerts carry additional context such as reading time, pictures, and graphical elements

Analysis shows that BBC News in the UK will typically send up to ten alerts each day.3 These mostly deal with breaking stories of national or international importance, with many containing a link to a live video feed or live blog to encourage further consumption. At times the BBC also uses its notification service to promote an exclusive feature, investigation, or piece of analysis, though this wider remit is not always welcomed: ‘I value news alerts that are truly breaking news rather than just everyday stories seeking clicks’, says one UK survey respondent. But not all publishers are so restrained. The Jerusalem Post and CNN Indonesia typically send up to 50 alerts each day and some aggregator apps will send even more.

Average number of push alerts by selected publisher

Source: Project Push (courtesy Matt Taylor)

It may be that in some countries where news remains highly prized, there is a tolerance for a higher number of alerts but tech companies that run mobile operating systems such as Apple and Google have routinely warned publishers about sending too many alerts. Apple has started to group messages together and even to summarise duplicative ones using artificial intelligence (AI), though this feature was withdrawn after a number of mistakes. Despite this, publishers worry that platforms could further restrict or mediate their notifications in the future.

Conclusions

In this chapter we find that, across countries, news alerts are used mainly by those who already have a high level of interest in the news. They keep those users engaged and bring them back more frequently to an app. Most people use news alerts in combination with other forms of media, not as a replacement.

From an audience perspective, alerts are an easy way to keep up to date, as well as to widen perspectives beyond breaking news. They are not valued, however, when they use over-sensationalised headlines (clickbait) or when publishers send too many alerts that do not feel relevant.

In some countries, such as the UK, people seek out alerts from well-trusted news brands that have a strong reputation for breaking news and a track record for accuracy. This could give incumbent brands a significant advantage, but elsewhere breaking news alerts can come from a wide variety of sources including social media, video networks, and aggregator apps. These alerts tend to be personalised and often offer a much broader range of stories, even if some of the sources may be less reliable.

Competition on the lockscreen is becoming more intense, with news jostling for attention with updates from multiple social networks, games, and entertainment apps. In this high-choice environment news organisations will need to be even smarter in how and when they use alerts to keep users engaged without causing them to unsubscribe. Audiences want more personalised and relevant content but they also don’t want to miss out on important national and international news. Some users just want breaking news, others are happy to be alerted about lighter stories or specialist news. Squaring these various circles will require a deeper understanding of these very different audience needs – and then varying the content, the format, and the time of day accordingly. Providing users with ways to vary the number and type of alerts will also be important. Moving away from using push alerts as a blunt instrument and providing more personal choice and control could yet help publishers sustainably grow engagement on their critical mobile platforms.

Footnotes

1 USA, UK, Germany, Japan, Brazil, India, Kenya, and South Africa.

2 Ipsos Iris official app chart shows 12.6 million UK users in October 2024.

3 Author analysis based on a push alert tool developed by Matt Taylor (Financial Times) that tracks news alerts from over 100 news providers over the last two years.