As newsrooms continue to experiment with AI technologies, many are setting their sights on tools to help tackle declining news engagement and growing news avoidance, especially among younger audiences, while also cultivating loyalty among those who already rely on them. While personalisation is not new to the news industry, where many have implemented recommendation systems and tailored newsletters for some time (e.g. Kunert and Thurman 2019), recent developments in AI have drastically changed the kinds of personalisation that are potentially feasible at scale.1

In addition to enabling further personalisation in the selection of news, generative AI now makes it technically possible to personalise news formats according to the needs and preferences of individual users, while also enabling entirely new possibilities, such as generative AI chatbots that can answer news-related questions. To the extent that these tools work reliably in practice, they may enable organisations to deliver news in ways that are more accessible, convenient, and relevant to individual users. However, achieving this will partly depend on how audiences feel about using personalised news in the first place, in addition to how open they are to the use of AI for this purpose, in a context where many remain sceptical about these technologies.

I begin this chapter by exploring audience attitudes towards the personalisation of content selection across different kinds of websites and apps, showing how comfort with algorithmic recommendation in news compares to other domains. Then I move onto AI-driven personalisation, first showcasing examples of how newsrooms are already experimenting with these technologies, before examining public interest in different types of AI-driven news personalisation.

A podcast episode on the findings

Spotify | Apple | Transcript

Comfort with personalised selection across domains

Automated personalisation has become an increasingly common feature of digital life, yet the nature, utility, and implications of relying on personalised content differ considerably depending on the kinds of content being personalised. To contextualise audience comfort with the personalisation of news selection, we first asked survey respondents in 27 markets about their comfort using websites or apps with automated selection across different kinds of websites and apps.

We find that close to half of respondents are comfortable with news personalisation, but comfort is low compared to other domains. Respondents are most comfortable with automated selection when it comes to weather, where people tend to be more interested in places they are or will be. Majorities are also comfortable with the automated selection of music and online television, which many are accustomed to on platforms such as Netflix and Spotify, and where people tend to see benefits of recommendations based on genres they like and may appreciate being freed from the burden of having to choose. Comfort is lower for news, where important stories of the day can be about almost any topic. Comfort is lowest on social media and video feeds (e.g. YouTube, TikTok), where some may have had negative experiences or encountered more public debate on the matter. However, younger people – who are heavier users of platforms like TikTok, where algorithmic recommendation is integral to the user experience – tend to be much more comfortable with automated selection on social media (54% among under-35s vs 38% among those 35+). Across all domains, comfort tends to be lower in much of Europe (e.g. Western and Northern Europe) compared to other parts of the world (e.g. Latin America, Asia, Africa).

This begs the question of what beliefs drive people’s attitudes towards personalised news selection. An analysis of open comments from a subset of countries shows that respondents who are comfortable with personalised news selection see four key benefits. First, many feel personalisation ensures they receive news that is more relevant to their lives, for example, ‘highlighting information about my city, my province’ (F, 34, Argentina). Relatedly, some emphasise the greater efficiency of personalised news selection, which helps bypass topics that are uninteresting or which they intentionally avoid: ‘It always knows … the relevant information I need, instead of wasting time viewing everything’ (M, 24, US). A smaller number of respondents express greater trust in news selection performed by algorithms, which they view as ‘less biased than human editors, as they are programmed to make selections based on data rather than personal opinions or preferences’ (M, 26, US). Lastly, some believe algorithmic selection delivers more varied topics and viewpoints, serving ‘articles that I wouldn't have seen myself that are relevant’ (F, 47, UK). Across all four themes, participants think these technologies work well and, as a result, benefit them.

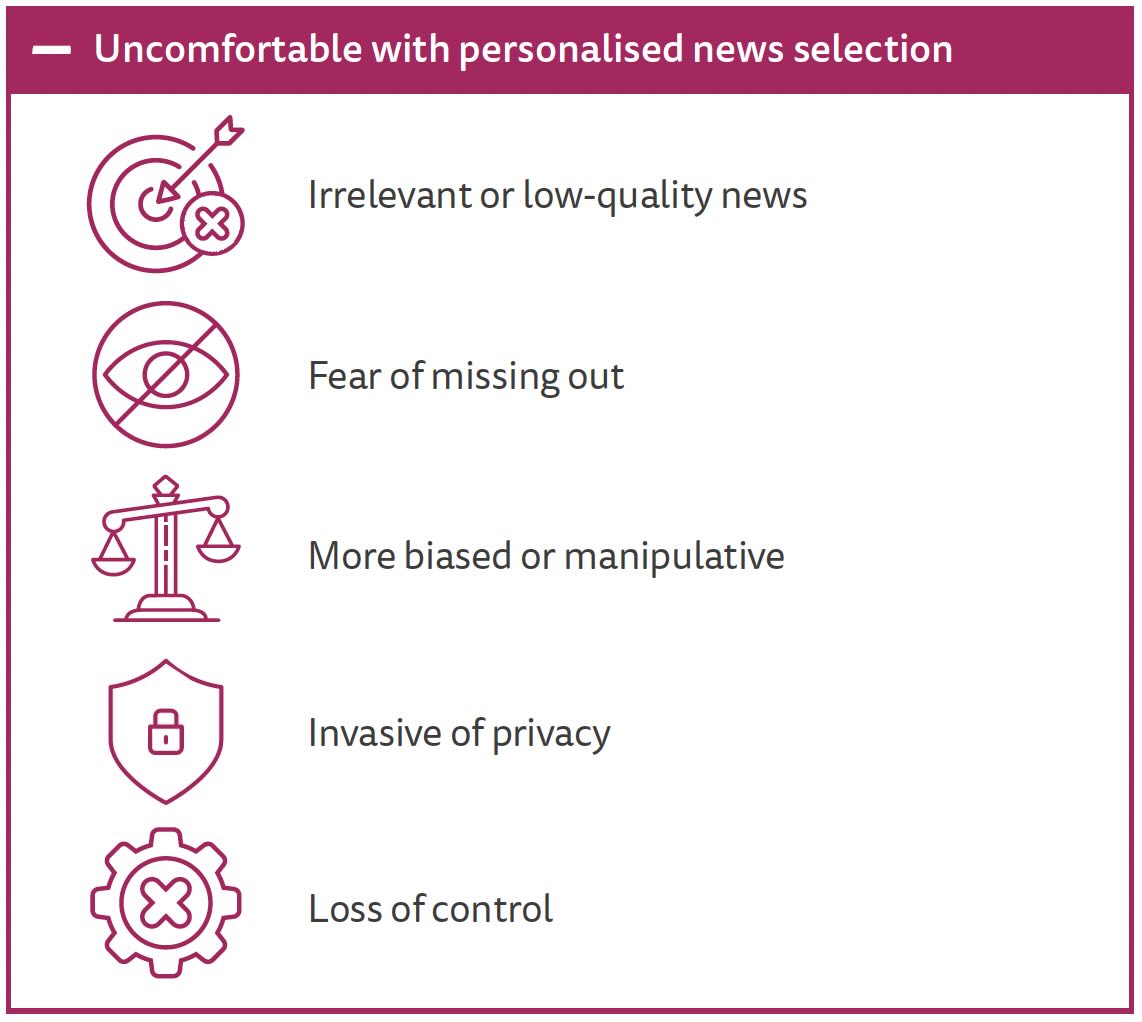

The reasons underpinning discomfort with personalised selection vary more, with some opposing these technologies rooted in a belief they do a poor job, while others are uncomfortable precisely because they think they are effective but may have negative outcomes, and others yet express concerns that go beyond the quality of the recommendations. For instance, some feel these technologies are bad at predicting their interests, delivering content that is ‘useless or false’ (F, 57, Argentina), or as one participant put it, ‘because the algorithm is always wrong about me’ (F, 61, US). However, others worry that, in adhering to their personal interests, algorithmic selection may lead them to miss out on important issues, preferring instead ‘a general overview rather than only specific pre-selected areas of knowledge’ (F, 76, UK). Likewise, some believe personalised selection leads to more biased (or worse yet, manipulated) information, which some associate with echo chambers and polarisation: ‘I worry that the algorithmic filtering might block out important stories and may also be intentionally manipulated’ (M, 34, Argentina). Beyond news content itself, many express concerns about the ‘invasion of privacy’ (M, 60, UK) by surveillance technologies – ’Big brother is watching’ (M, 52, US) – or simply oppose personalised selection grounded in a desire to make up their own minds about news and what to consume: ‘I don’t like news to be imposed on or chosen for me’ (M, 56, Argentina).

Reasons people are comfortable vs uncomfortable with personalised news selection

Some of these concerns may be assuaged through communication and/or design, clarifying for users what personalisation consists of and any measures taken to minimise potential risks (e.g. approaches in which big stories of the day will remain prominent regardless of individual preferences). However, the broader question of how enthusiastically to lean into audience preferences remains important to the extent that it risks undermining editorial values and public interest, a concern that is especially salient for public service media (e.g. Sehl and Eder 2023).

Growing interest in AI personalisation in the news industry

While personalised news selection has been around for some time, it is increasingly AI powered. Of the media leaders surveyed for the Reuters Institute’s latest Journalism, Media and Technology Trends and Predictions report, 80% said AI would be very or somewhat important in 2025 for news distribution and recommendation, such as personalised homepages and alerts (Newman and Cherubini 2025). Media leaders are increasingly setting their sights on more ambitious AI personalisation initiatives that account not only for news selection but also the formats in which content is offered. As Deborah Turness, chief executive of BBC News, said in her announcement to staff about the creation of a new department that will use AI to deepen personalisation: ‘We must become ruthlessly focused on understanding our audience needs, on delivering the kind of journalism and content they want, in the places they want it, designed and produced in the shape that they enjoy it.’2

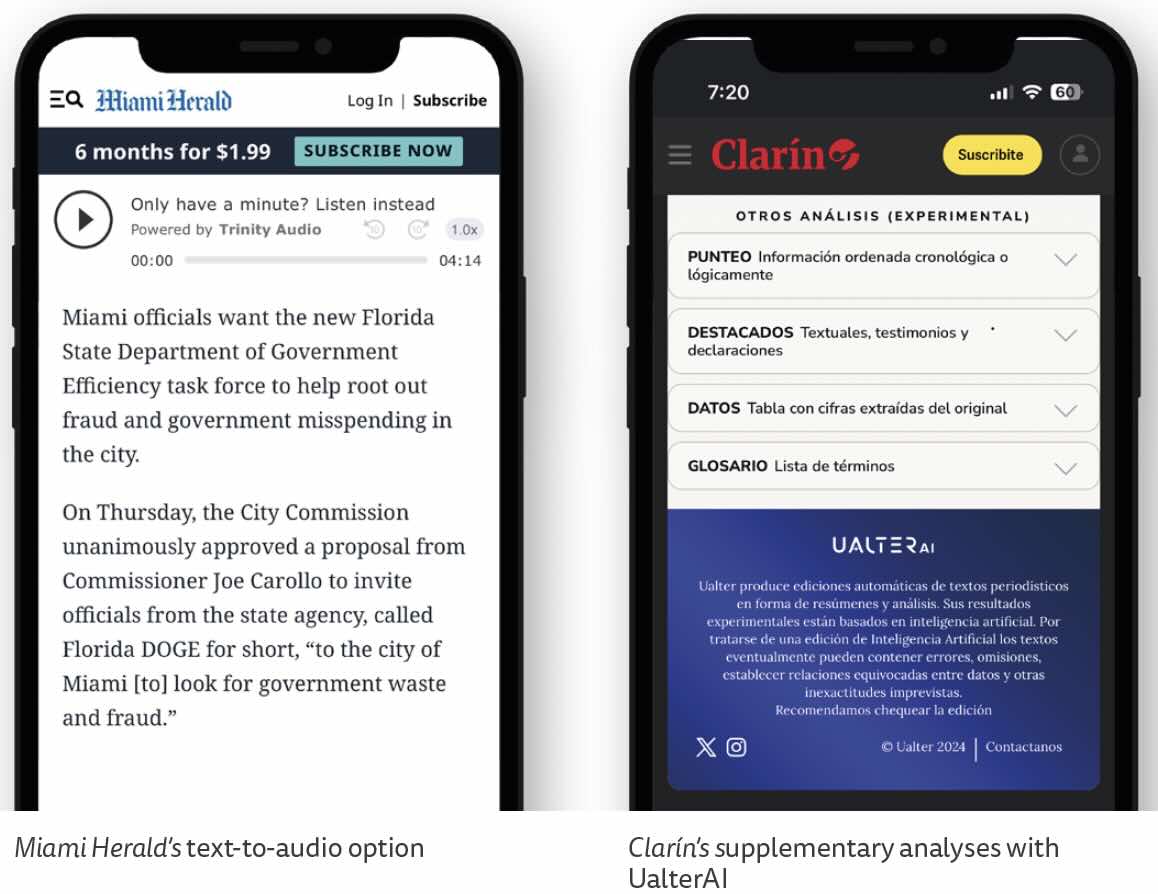

Publishers are already experimenting with AI to personalise news formats. The BBC has been trialling OpenAI’s speech-to-text tool Whisper to add subtitles and transcripts to some items published on BBC Sounds. Others, such as India Today and the Miami Herald, have been testing the opposite – AI technologies that allow users to turn text articles into audio, using an AI-generated voice. Swedish newspaper Aftonbladet has introduced ‘quick versions’ of news stories produced with AI on top of extended versions of articles. And Argentina’s Clarín newspaper now offers users both a text-to-audio option and UalterAI, a tool offering a range of supplementary analyses ranging from key bullet points and highlighted quotes, to key figures, a glossary, and a list of Frequently Asked Questions.

Examples of AI used to adapt news formats and delivery

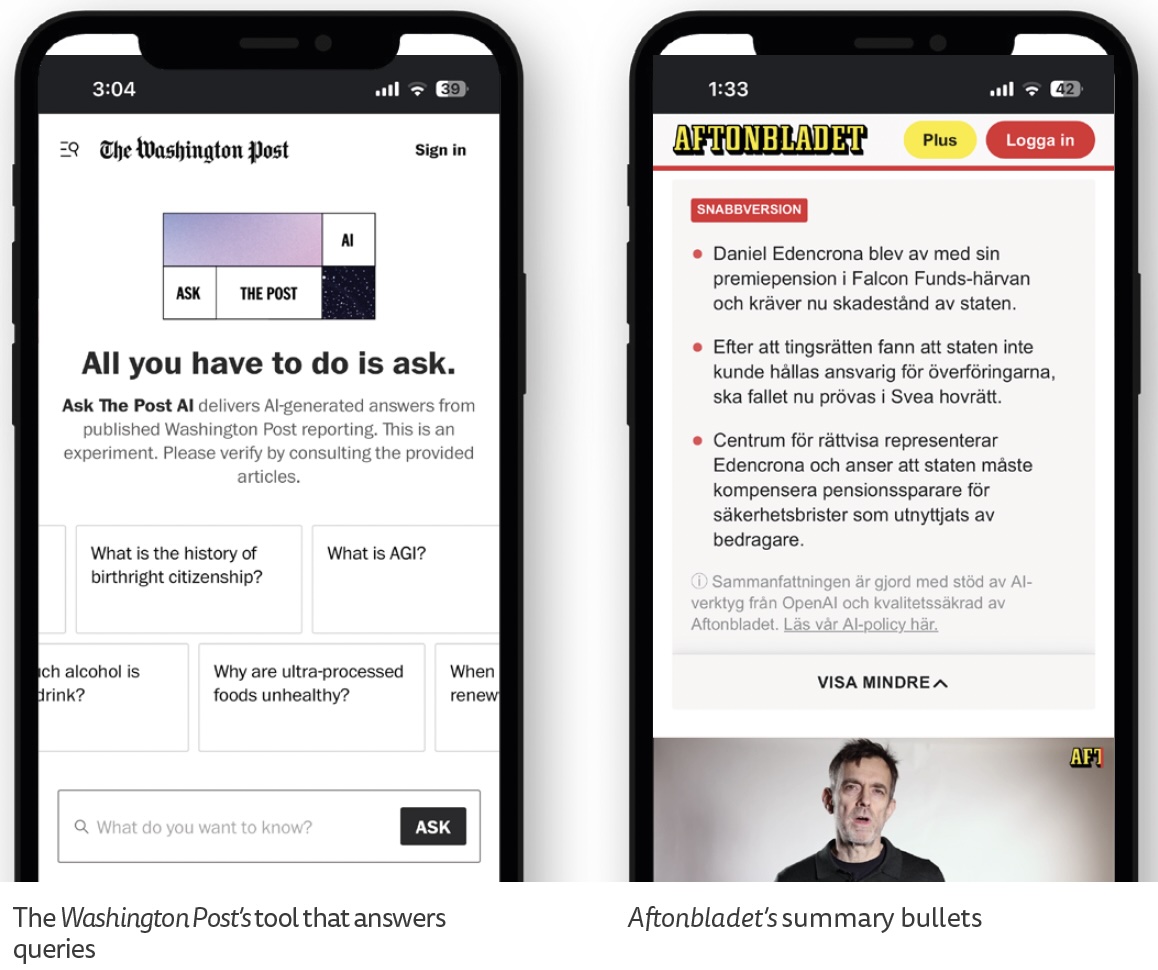

Other publishers are introducing entirely new products. The Independent (UK) has launched a new digital news service called Bulletin – advertised as ‘News for Seriously Busy People’ – which uses Google AI tools to create article summaries overseen by journalists.3 Others such as the Washington Post (US)4 and the Financial Times5 (UK) have launched generative AI tools that can answer user questions based on their own corpus of articles. Rather than modifying news story formats, these tools provide an advanced search function that can understand complex queries.

Audience interest in AI-driven news personalisation

When we ask audiences about their interest in different options for adapting news to their individual needs with AI, we find relatively low interest across the board – below 30% for any single option, which may be shaped by low familiarity with these kinds of tools. We see a greater appetite for alternatives that make news consumption more efficient and relevant: article summaries and translations of news articles are at the top of the list, followed by customised news homepages and recommendations or alerts. Meanwhile, interest is lowest in modality conversion options such as text-to-audio. This contrasts with the high interest reported among industry leaders for AI format conversion options, where text-to-audio tops the list of AI initiatives planned for 2025, perhaps because it is seen as relatively easy, cheap, and uncontroversial to implement (Newman and Cherubini 2025).

Relative interest in different types of AI personalisation also varies somewhat across markets. While article summarisation – one of the more widely rolled out generative AI features – tends to be of high interest everywhere, translation more often tops the list in linguistically unique European countries with relatively small populations, such as Finland and Hungary, perhaps signalling an appetite to be able to access news content from outside their countries. Likewise, interest in the ability to adapt news text to different reading levels often ranks higher in countries with lower literacy rates or reading proficiency relative to countries with higher literacy or reading proficiency levels. In India, Kenya, Nigeria, and the Philippines, the option to adapt news to different reading levels ranks in the top three, and in India is the most popular option. This compares to countries like Finland, Norway, and Japan where adapting the language in news articles for different reading levels ranks in the bottom three.

More broadly, respondents tend to express more enthusiasm in countries where comfort with the use of AI in journalism is higher, such as India and Thailand, whereas we see much lower interest in countries with low AI comfort, such as the UK. Likewise, younger groups, who tend to be more comfortable with AI in general, show greater interest in the use of AI for personalising formats, such as adapting articles to different reading levels, as well as chatbots. This suggests that news organisations may want to focus these kinds of AI innovation on younger audiences. Likewise, respondents who are less keen on reading news show greater interest in options to convert text to audio or text to video.

There is also the question of how effective such tools are likely to be among people disengaged from news. Our data show that interest in AI personalisation is considerably lower among those least interested in news and those who avoid news more frequently. That said, small pockets of news avoiders may be more amenable to certain types of personalisation. For example, those who avoid news because they find it hard to understand express higher interest across the board relative to news avoiders in general, with the largest gap when it comes to the use of AI to adapt news for different reading levels.

Conclusion

Audiences are broadly sceptical about news personalisation in ways they aren’t about other areas of digital life. Our research finds greater interest in the use of AI to personalise news formats, particularly those that make news easier or quicker to consume, followed by personalised news selection, where some already worry about algorithmic recommendation, including fears about missing out on important stories. Reported interest does not necessarily mean people will use options, just as lack of interest doesn’t necessarily mean they won’t (and it is possible some respondents don’t understand what each would entail or look like in practice). However, there is a risk of overestimating public enthusiasm around AI-driven personalisation or prioritising tools audiences are less interested in. It is also possible, given relatively low appetite for any single option, that offering a palette of options for audiences to choose from may be necessary in order to add value for a critical mass of users.

We find evidence that interest in AI personalisation is shaped both by comfort with the use of AI in journalism and the potential these technologies show in satisfying audience needs or preferences. In light of this, the rollout of AI personalisation may play out differently from one country to the next, with greater openness and enthusiasm in markets such as Thailand, India, and much of Africa, where attitudes towards the use of AI in news are more favourable, compared to Northern and Western Europe, where audiences are considerably more sceptical about AI. Likewise, news organisations will need to evaluate possible strategies and potential trade-offs of serving these options to audiences who have more of an appetite for them (e.g. younger people) without being off-putting for more hesitant users.

Given that AI can power such different kinds of personalisation, communicating clearly what these technologies consist of may help offer reassurance in light of some of the concerns identified in our open responses, especially regarding personalised selection. It is also worth keeping in mind the desire for self-determination expressed by many respondents in the open responses. While the uptake of customisation tends to be limited, offering audiences options to exercise some control over personalisation might help placate concerns, especially in the early stages of AI adoption.

Footnotes

1 Some in industry circles differentiate personalisation (understood as the automated selection of news content based on user data) from customisation (referring to when users can choose or configure their own news experiences). In this chapter, we use personalisation more broadly to describe different scenarios that enable the tailoring of news to the needs and preferences of users, regardless of whether it is automated or selected by users.

2 https://www.theguardian.com/media/2025/mar/06/bbc-news-ai-artificial-intelligence-department-personalised-content

3 https://www.independentadvertising.com/the-independent-launches-bulletin-a-new-brand-delivering-essential-news-briefings-for-seriously-busy-people/

4 https://www.washingtonpost.com/ask-the-post-ai/

5 https://www.ft.com/content/fc5d4642-af71-4ac6-8311-1920726f8baa