Artificial intelligence (AI) and similar technologies have been used by news organisations for some time, but these uses have been largely behind the scenes. However, recent developments in Large Language Models (LLMs) and the public launch of ChatGPT in late 2022, followed by a flurry of other generative AI tools, marked a real shift in public interest and in how publishers have been thinking about AI for the production of news content.

Research on the uptake of AI in newsrooms is rapidly growing, (e.g. Beckett and Yaseen 2023; Simon 2024), but we know considerably less about how news audiences might receive these incursions, especially in a context of low or declining trust in news in many countries. We have included questions on the topic in this year’s survey, at a time when audiences themselves are learning and forming their own opinions about AI in general and few will understand how these technologies might be used in journalism specifically.

In the analysis that follows, we supplement our survey data with illustrative quotes and insights from qualitative research conducted by the market research agency Craft with 45 digital news users in Mexico, the UK, and the US. The research took participants on an individual ‘deliberative journey’, capturing their baseline understanding and comfort levels with AI in initial interviews, and then presenting them with news-related AI case uses to experiment with and reflect on. Just as publishers can use AI for different kinds of tasks, audiences approach distinct uses with varying degrees of comfort, more generally onboard with backend tasks and innovation in the delivery of news than with the generation of new content.

A podcast episode on the findings

Spotify | Apple | Transcript

AI awareness and how it shapes comfort with AI in journalism

Before asking respondents about AI in news, we wanted to have a sense of their awareness about AI more generally. Across 28 markets where AI questions were included, self-reported awareness is relatively low, with less than half (45%) of respondents saying they have heard or read a large or moderate amount about it. Meanwhile, 40% of respondents say they have heard or read a small amount, and 9% say nothing at all.

Aside from country-level differences, AI awareness varies across socio-demographic groups, with marked gaps across age, gender, and education levels. On average, we find that AI awareness is higher among younger people, men, and those with higher levels of education.

These figures give us a sense of how much information about AI respondents have encountered, but not where they have seen it, what kind of information it is, or what experiences they have had with AI themselves. Recent studies suggest people don’t always recognise what AI is, and most are not using it on a regular basis.1 Evidence from our qualitative data echoes these findings, also showing that, while a small subset of people may already be using AI tools and many will have encountered information about it in the news and social media, for others, science fiction TV series and films also shape their perceptions.

AI is in all the devices we use now – phone, computer, in everything we do on the internet. And there are more advanced things like ChatGPT that students now use a lot.Female, 26, Mexico

It worries me slightly, if we do become very dependent on AI and AI becomes a big thing, how AI can basically just destroy the world. It's a very ‘out there’ take, but it's one of those we just can't help think about. I adore sci-fi, The Terminator, Space Odyssey.Male, 19, UK

Understanding how much people have seen or heard about AI is important for publishers because, in the absence of personal experience, popular portrayals play an outsized role in colouring perceptions of AI overall, which in turn shape attitudes towards using news made with or by AI – something most have likely not seen that much of yet. Our survey data show that, across all countries, only a minority currently feels comfortable using news made by humans with the help of AI (36%), and an even smaller proportion is comfortable using news made mostly by AI with human oversight (19%).

We also find that people with greater AI awareness tend to feel relatively more comfortable with the use of AI in journalism. While still very low, comfort using news made mostly by AI is twice as high among those who have seen or heard more about AI (26%) relative to those who have seen less (13%). We see a similar gap when asking about comfort using news produced mostly by a human journalist with some help from AI (45% versus 30%).

Different comfort levels for different AI uses

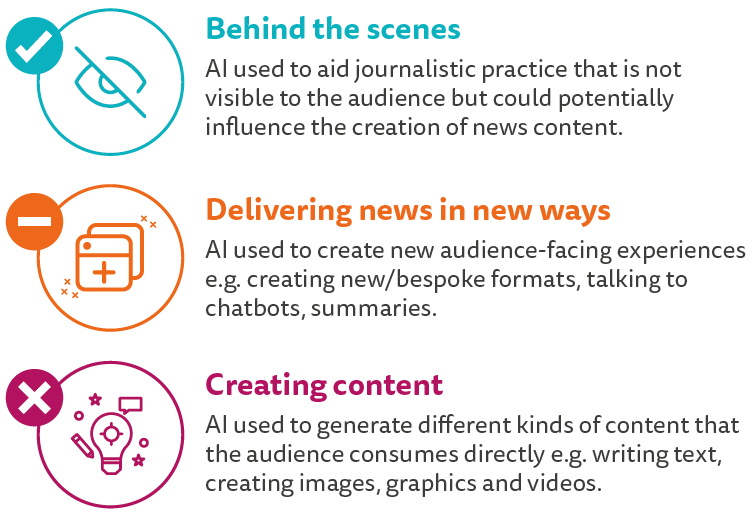

Most audiences have not put much, if any, thought into how AI could be used for news, and our qualitative research shows that people’s starting point is generally one of resistance, suspicion, and fear. However, over the course of testing out a variety of AI use cases in journalism, participants often developed and articulated more nuanced opinions about where they were more or less comfortable with the implementation of AI, depending on whether it is used behind the scenes, to deliver news in new ways, or to generate entirely new content. Perceptions about AI are rapidly evolving, and while majorities are put off by AI news in principle, it is possible that, as audiences become more familiar with AI, some may become more open to its adoption for at least certain functions.

If it was disclosed to me that this was produced by an AI [I] will probably go, ‘Okay, well, then I'll just not read that.’UK, 40, Male

Many publishers have, for years, used AI and similar technologies for behind-the-scenes tasks such as monitoring trending topics online, transcribing interviews, and personalising recommendations for readers (Beckett 2019). However, concerns with guardrails and best practices have become salient as more newsrooms explore using generative AI for increasingly public-facing applications. For example, in the US, Men’s Journal has used AI to help write summary pieces based on previous articles. In Mexico and the UK, radio and TV channels have experimented with synthetic newsreaders. Others have trialled applications like headline testing, summary bullets, chatbots, image generation, and article translation. Still, most publishers are moving cautiously, learning from the mishaps of others who have come under scrutiny for insufficient disclosure and oversight, in some cases resulting in inaccurate information making its way onto news websites.2

Our qualitative research tells us that people tend to be most comfortable with behind-the-scenes applications, where journalists use AI to make their work more efficient and in ways not directly visible to audiences. They are less comfortable with, but in some cases still open to, the use of AI for delivering news in new ways and formats, especially when this improves their experiences as users and increases accessibility. They are least comfortable with the use of AI to generate entirely new content. Regardless of the application, there is widespread agreement that total automation should be off limits and a human should always remain ‘in the loop’ – which coincides with how most publishers are thinking about the implementation of generative AI.

Audience comfort with the use of AI across different stages of news production

I am somewhat/mostly comfortable with … AI manipulating and reformatting information to some extent, but AI does not seem to be intentionally creating new content in these scenarios.Female, 24, US

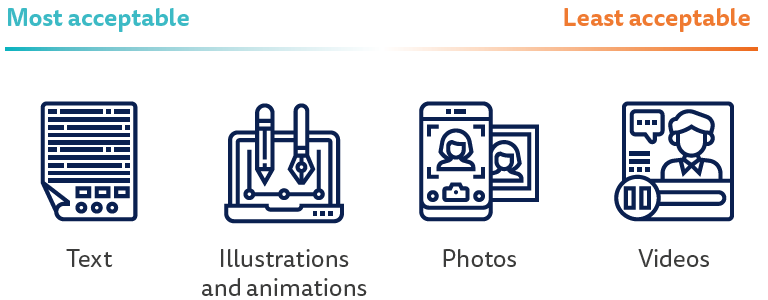

While audiences tend to be uncomfortable with the use of AI to create new content, not all forms of content are seen equally. We found participants to be least resistant towards the use of AI to generate text-based content, followed by illustrations or stylised graphics and animations, which many reasoned are nothing new and add aesthetic appeal. Meanwhile, they are most strongly opposed to the use of AI for creating realistic-looking photographs and especially video, even if disclosed. Past research shows that people often rely on images and videos as ‘mental shortcuts’ when trying to discern what to trust online, with many expressing the idea that ‘seeing is believing’ (e.g., Ross Arguedas et al. 2023). This crucial function of images, often serving as proof of what is being reported, helps explain why synthetic imagery disrupting that logic would cause greater uneasiness.

Some uses of AI do not alter anything, they are graphics, complementary images and can make the content more attractive.Female, 24, MexicoFor producing images and things like that, that is a little more tricky because it can generate images that appear to show something that is not reality, especially when given the prompts by the author.Male, 41, US

Examples of different formats shown to research participants

As noted in the Executive Summary, the topic at stake also shapes comfort levels. While comfort levels are low across the board, audiences express greater discomfort with the use of AI to generate content about more consequential topics, such as politics, relative to less consequential topics such as sports. In our qualitative research, participants note that the potential to cause harm and the scope of such harm varies considerably depending on the subject matter.

Different types of news carry different weights. AI fact-checking football game scores … for a sports article has almost no consequence if it reports something incorrectly/with bias. Fact-checking an article about a political party or election news could have catastrophic consequences.Non-binary, 24, US

The type of information being generated also shapes perceptions, as some people are more open to the use of generative AI for creating outputs based on verifiable ‘facts’ and ‘numbers’, such as sports scores or even elections reports, than they are when it comes to more complex news they believe requires human interpretation, nuance, sensitivity, and even emotion. Such distinctions are not only about accuracy, but also about more philosophical questions around what journalism is and what kinds of work people think are and should remain fundamentally human.

The best thing is to try to keep the use of AI to facts, numbers, statistics, and not analysis or opinion, where more context needs to be given. That is where humans are needed, to provide that value.Female, 52, MexicoWhen you're delivering, like, really triggering and hopeless news, it’s very emotional. Regardless of whether you want it to, it will affect you in some way or other, and I feel like humans kind of have that emotional context.Male, 19, UK

AI news, disclosure, and trust

One key concern for publishers experimenting with AI is how using these technologies may impact public trust in news, which Digital News Report data show has declined in many countries in recent years. Many worry about the potential for AI to generate biased, inaccurate, or false information. However, beyond ensuring information quality, some are grappling with best practices around disclosing AI use. On the one hand, providing transparency about how they are using AI may help manage expectations and show good faith. On the other hand, to the extent that audiences distrust AI technologies, simply knowing news organisations are using them could diminish trust. Early experimental research suggests that audiences view news labelled as AI-generated as less trustworthy than that created by humans.3 This tension means that news organisations will want to think carefully about when disclosure is necessary and how to communicate it.

It is very important that there is human supervision. I trust a human more, because we have the ability to analyse and discern, while AI is not sensitive, it has errors, it does not know how to decide what to do … it does not have a moral compass.Male, 28, Mexico

When asked about disclosure generally, participants in our research welcome and often demand complete transparency about the use of AI in journalism. However, when probing further on diverse AI applications, not everyone finds it necessary across all use cases. Some view labelling as less important when it comes to behind-the-scenes uses where human journalists are using AI to expedite their work but imperative for public-facing outputs, especially those made mostly by AI, since it might shape how they approach the information or whether they want to use it in the first place.

I don't think they need to disclose when [it’s] … behind the scenes and it's still [a] human interacting with both those services. It's still human-based, they're just helping with assistive tools, so I think it's fine and it speeds up the process a lot.Male, 26, UK

News organisations and journalists should always let consumers know that they have used AI. I think there are net benefits in that kind of transparency … so consumers can make the decision themselves of whether they want to consume this content or not.Female, 28, US

Furthermore, trust can itself shape how comfortable audiences are with using news produced by or with the help of AI. We find that trusting audiences tend to be more comfortable, particularly when it comes to using news produced mostly by humans with the help of AI, with gaps in comfort levels between trusting and untrusting audiences ranging from 24 percentage points in the US to 10 percentage points in Mexico. It is likely that audiences who tend to trust news in general have greater faith in publishers’ ability to responsibly use AI, relative to their untrusting counterparts.

We see evidence of this in our qualitative findings as well, both in general and at the outlet level. Individuals who trust specific news organisations, especially those they describe as reputable or prestigious, also tend to be more open to them using AI. Whether it is because they view such outlets as more benevolent, have greater faith in their oversight capacities, or simply think they have the most to lose if they do it carelessly, these segments of the audience appear less uncomfortable with journalists using AI. On the flipside, audiences who are already sceptical or cynical of news organisations may view their trust further eroded by the implementation of these technologies.

It depends on who uses it … If a serious, recognised, prestigious news company uses it, I feel that it will be well used, because I don't think a company will put its prestige at play.Male, 28, Mexico

Conclusion

Just as there is no single AI technology or application, there is no single view from audiences on whether the use of AI by news organisations is acceptable or not. While the starting point is largely of resistance, when examining specific uses, audiences express nuanced opinions across a range of different applications, and our findings highlight the areas they seem more comfortable accepting as well as those that are more likely danger areas, where news organisations will want to tread lightly or entirely avoid.

Our findings show audiences are most open to AI uses that are behind the scenes and areas where AI can help improve their experiences using news, providing more personalised and accessible information. They are less comfortable when it comes to public-facing content, sensitive or important topics, and synthetic videos or images that may come across as real, and where the consequences of error are viewed as most consequential. Overall, there is consensus that a human should always be in the loop and complete automation should be off limits.

Carefully threading the needle when it comes to disclosing the use of AI will be crucial for publishers concerned with audience trust, as will be explaining to audiences what AI use in journalism looks like. Excessive or vague labelling may scare off individuals with already low trust and/or those with limited knowledge about what these uses entail, who will likely default to negative assumptions. But failing to provide audiences with information they may want to decide what news to use and trust could equally prove damaging.

These are still early days, and public attitudes towards the application of AI in journalism will continue to evolve, especially as the balance between abstract considerations and more practical experience shifts if larger parts of the public use AI tools more in their personal and professional life. At present, many are clear that there are areas they think should remain in the hands of humans. These kinds of work – which require human emotion, judgement, and connection – are where publishers will want to keep humans front and centre.

Footnotes

1See ONS and Pew Research Center.

3 https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:5f3db236-dd1c-4822-aa02-ce2d03fc61f7/files/s9306t097c