What does India’s mobile-first, platform-dominated news ecosystem mean for the upcoming general elections?

In less than a month, India will hold its general elections, what some call the world’s largest democratic exercise. Politicians and news publishers have been gearing up towards the event for the past couple of months, with the former campaigning across the country and the latter trying to keep citizens informed in any way they can. Equally busy are Facebook, Twitter and Google.

This is unsurprising, not just because these technology giants have become crucial platforms for the two rival parties—Bharatiya Janata Party and Indian National Congress—but because politicians, activists and fringe groups have embraced digital media, especially social media and mobile applications, to spread their message, sway opinions and organise supporters on a massive scale. This is made possible partly because these platforms are emerging as the primary source of news for a significant number of news consumers.

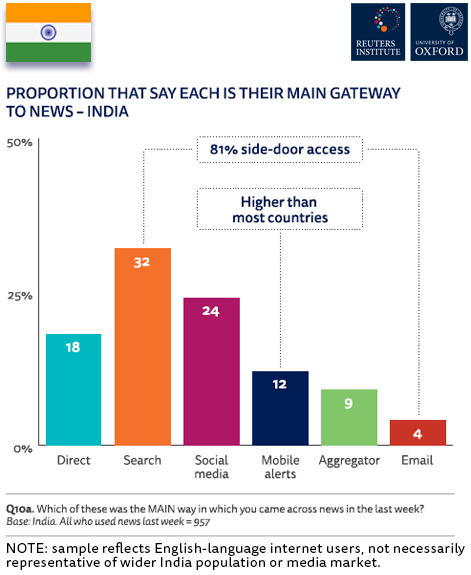

The Reuters Institute’s India Digital News Report, published today, found that almost a third access news mainly through search engines, while just under a quarter identify social media platforms as their main source of online news. The study not only offers us a snapshot of the emerging trends in English language news consumption in India but also provides insights into more pressing issues like trust in the news, concerns over disinformation and the future of news. Some of these findings could be important to understand how news and information will be accessed, consumed and shared during the final days of the campaign.

Accessing news on informational battlegrounds

More than four-in-five of the study’s respondents identify search, social media, mobile alerts and other ‘side-doors’, over which news publishers have little control, as their main way for accessing news. This is higher than in comparable markets such as Brazil and Turkey.

The New York Times quotes an Aam Aadmi Party worker as saying “We wrestle on Twitter. The battle is on Facebook. The war is on WhatsApp.” If this is indeed true, we are presented with a scenario where many of our respondents are getting their news from spaces that are inundated with, often conflicting, information from a variety of stakeholders.

Worryingly, we found that the increased use of digital platforms for news is not accompanied by a rising literacy in how platforms work; our data shows that there is limited awareness of the fact that algorithms curate news on social media platforms— 18% believed these decisions are made by editors and journalists working for each platform. While political parties and leaders are taking to these platforms to express their views, many users are concerned with airing their own, at least according to our study. Around half felt that openly expressing their political views online could impact how their friends of family (49%), colleagues or other acquaintances (50%) think of them. Most worryingly, perhaps, 55% fear it could get them into trouble with authorities.

Concerns around disinformation abound

The reach and convenience of these platforms enable dissemination of important news to wide audiences, but has in some instances also helped spread disinformation and rumours. In the run up to the Karnataka state legislative elections last May, both BJP and Congress claimed to have at least 50,000 WhatsApp groups between them to spread their political messages.

Over 35% of our respondents reported to have been exposed to some form of disinformation in the week of taking the survey. Additionally, 57% say they are concerned about what news is real and what is fake online: they worry about hyperpartisan content (51%), poor journalism (51%) and news that is completely made up (50%). Most people also felt that the responsibility of tackling the disinformation problem lies with the government, publishers, and platforms.

Such efforts to combat disinformation are underway. Publishers are setting up fact checking operations, and government-funded initiatives in over 150 schools are teaching children how to be more wary of fake news. At the same time, Facebook (including WhatsApp and Instagram), Twitter, and even YouTube are taking steps to fact check and curb the spread of disinformation on their platforms.

Potential market for compelling news

Apart from these findings, the report also captures a sense of audience attitudes towards online video, emerging technologies like voice-activated speakers, and willingness to pay or donate to access news. Increasing use of ad-blocking among Indian users and an increasingly competitive market for online advertising puts Indian publishers’ reliance on advertising at risk. Our study suggests that publishers who invested in mobile strategies are seeing a return as smartphones also offer new ways of serving their users—12% of our respondents identified mobile alerts as their main way of accessing online news. While content on their website remains free, NDTV and Economic Times are experimenting with subscription plans on their mobile applications.

Promisingly, our survey documents a considerable willingness to pay for online news in the future—39% of those who currently don’t pay for news said they are at least ‘somewhat likely’ to pay for news in the next year and 9% said they were ‘very likely’ to pay for online news in the future. This suggests that a potential market exists for publishers who will invest in creating a compelling news product.

(Photographer: Shailesh Andrade)