A journalist films a medical worker drawing the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine in Nanterre, France. REUTERS/Benoit Tessier

A journalist films a medical worker drawing the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine in Nanterre, France. REUTERS/Benoit Tessier

2021 will be a year of profound and rapid digital change following the shock delivered by Covid-19. Lockdowns and other restrictions have broken old habits and created new ones, but it is only this year that we’ll discover how fundamental those changes have been. While many of us crave a return to ‘normal’, the reality is likely to be different as we emerge warily into a world where the physical and virtual coexist in new ways.

This will also be a year of economic reshaping, with publishers leaning into subscription and e-commerce – two future-facing business models that have been supercharged by the pandemic. While uncertainty has boosted audiences for journalism almost everywhere, those publishers that continue to depend on print revenues or digital advertising face a difficult year – with further consolidation, cost cutting, and closures.

An episode on the report

Listen to this episode: On Spotify | On Apple | On Google

For giant tech platforms, the pandemic has forced a rethink on where the limits of free speech should lie. With lives at stake, and under threat of regulation, expect a more interventionist approach on harmful and unreliable content and greater prominence for trusted news brands – along with greater financial support. By year end, journalism could be a bit more separated from the mass of information that is published on the internet.

New technologies like artificial intelligence (AI) will also drive greater efficiency and automation across many industries including publishing this year. But as AI moves out of R&D labs into real-life application, we can expect more heated debate about its impact on society – about the pace of change, about transparency and fairness.

How do media leaders view the year ahead?

And what else might surprise us?

More from the same author:

This time last year few could have predicted how our lives would be turned upside down – personally and professionally – by an invisible virus. There was no mention of Covid-19 in last year’s report, and yet it continues to cast a shadow over all of our plans, with its effects likely to be with us for years to come.

It has become something of a cliché to talk about Covid-19 as an accelerator but in this year’s survey, editors, CEOs, and other senior leaders have given us a practical insight into what this has meant for them. More than three-quarters of our sample (76%) say the pandemic has sped up plans for digital transformation and respondents say change breaks down into a number of areas: changes to working practices; to journalism and formats; to business models; and to the way media companies think about innovation.

1.1. Changing newsrooms and remote working

The most obvious shift in journalistic practice has been the forced adoption of remote working practices, using online collaboration tools like Zoom and Slack. Many previously resistant journalists found they liked the new flexibility, while news organisations found it was possible to create newspapers, websites, and even radio and TV news programmes, from bedrooms, living rooms, and kitchens. ‘Our newsroom went fully remote on March and we have been working like this since’, notes María Ramirez, Deputy Managing Editor at El Diario in Spain. ‘We’ll never return to the office with an old-style newsroom.’

Broadcasters mostly operated with a small number of key staff in the office supplemented by others in the field and at home. But at the height of the pandemic, some newspapers were being produced without anyone in the office – an industry first. The biggest stories of the year, including the police killing of George Floyd and the drawn-out, nail-biting US election results, were coordinated and packaged using online tools: ‘Having our entire team work remotely has been a game-changer’, says one of the newsroom leaders coordinating election coverage for one of the biggest US newspapers: ‘Covid forced the holdouts to get on board, which has improved internal communication, coordination and transparency.’

But while efficiency may have improved, newsroom leaders worry about the impact on creativity, at a time when long hours and the increased complexity of production have added to pressures on staff. As we revealed in our Changing Newsrooms report in October1, almost eight in ten (77%) think that remote working has made it harder to build and maintain relationships, with many managers raising concerns about how to communicate effectively and about the mental health of employees.

What will happen this year?

Learning lessons. A key challenge for the year ahead will be how to move from crisis mode towards a sustainable hybrid in-person/remote model. At the Straits Times in Singapore, Editor Warren Fernandez says they are re-examining the way the newsroom ‘works physically’ and introducing more flexible arrangements. Many journalists would like to continue working from home, but others can’t wait to get back to the office. That may be a problem as up to half of news organisations have active plans to downsize their physical premises to save money, according to our Changing Newsrooms report. Expect some choppiness as new working practices are established and new agreements between management and unions are thrashed out.

Face-to-face reporting could be making a comeback in 2021. The move to 24-hour online news has led more journalists to be chained to their desks, arguably contributing to a growing disconnect with audiences. This could be the year when that changes: ‘We’re accelerating plans to embed more journalists and teams in the community’, says Gaven Morris, Director News, Analysis & Investigations, for Australian public broadcaster ABC. The company has used the Covid-19 crisis to test new technology and newsgathering techniques. These include ‘advancing efforts to crowd-source content and explore audience-driven investigations’. Similar approaches have been tried in the UK by the BBC Local Democracy Reporting Service and by Facebook funding community reporters to cover under-represented areas.2

1.2. Refocusing journalism on facts, explanation, and specialism

One unexpected by-product of the pandemic seems to have been a renewed confidence amongst journalists about the value of their product. Despite the bleak economic outlook, confidence in individual companies remains surprisingly strong (73%), while confidence in journalism more widely has increased from 46% to 53%, when compared to last year’s survey. This may be partly because record audience figures during the coronavirus crisis have demonstrated the value that the public still places on reliable information:

One can call it a renaissance of the news. Corona has affected everyone, so fact-based reporting represents a lifeline for the vast majority of our audience.

Kaius Niemi, Senior Editor-in-Chief, Helsingin Sanomat

This validation of fact-based reporting comes against a backdrop of years of criticism of the news media by populist politicians, and critics on social media and elsewhere. In the early weeks of the crisis, the media showed strong innovation in digital formats to help explain the science.

Coronavirus explained

Companies that invested in specialist resources and talent before the crisis were in the best position to enhance their reputations. Health journalists and medical experts like Dr Norman Swan at the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Professor Christian Drosten working with German broadcaster NDR, and Dr Sanjay Gupta for CNN have become household names dispensing their knowledge across TV, radio, podcasts, and online – answering listener questions and helping to correct false information. Other publishers built on expertise in data and visualisation to provide context while websites have used personalisation functionality to help audiences quickly understand changing rules.

This matters because our own research shows that those who follow the news media closely know more about the pandemic and by implication are better equipped to stay safe.3 In our survey, media leaders clearly feel that unreliable information around coronavirus and other issues spread through social platforms has helped to strengthen the position of journalism (68%) rather than weaken it (22%) this year.

It is important to note that the media have not just amplified and explained official messages but have also delivered a number of powerful, independent investigations into governments’ handling of the crisis.4 Criticisms have not always gone down well with politicians and their supporters, especially in countries where even the issue of public health has become polarised. We can expect these tensions to be a continuing flashpoint in 2021.

What else can we expect this year?

Anti-vaxxer campaigns reach new pitch. Bottom-up activism and small well-organised groups drive much of the spread of anti-vaccine messaging. Popular posts and memes include suggestions that vaccines are part of a sinister plot to put microchips into people or that they are trying to re-engineer our genetic code. Expect to see tech platforms implement a more robust take-down policy, closing down anti-vaxxer accounts and groups, and labelling posts that share or spread untrue information. Media companies and social networks will need to be careful that damaging messages are not amplified in the process of fact-checking and debunking.

Newsrooms place more emphasis on specialism. This crisis has made many newsrooms realise how little they understand about science and technology – and the value of that rare breed of journalists that can explain these complex issues to a general public. ‘There is also a need to go faster in addressing priority subjects around broader environment and technology themes, as well as content for younger audiences’, argues Phil Chetwynd, Global News Director for the AFP News agency. With many newsrooms already under fire for an obsession with personality politics, expect a shift towards deeper and more diverse themes..

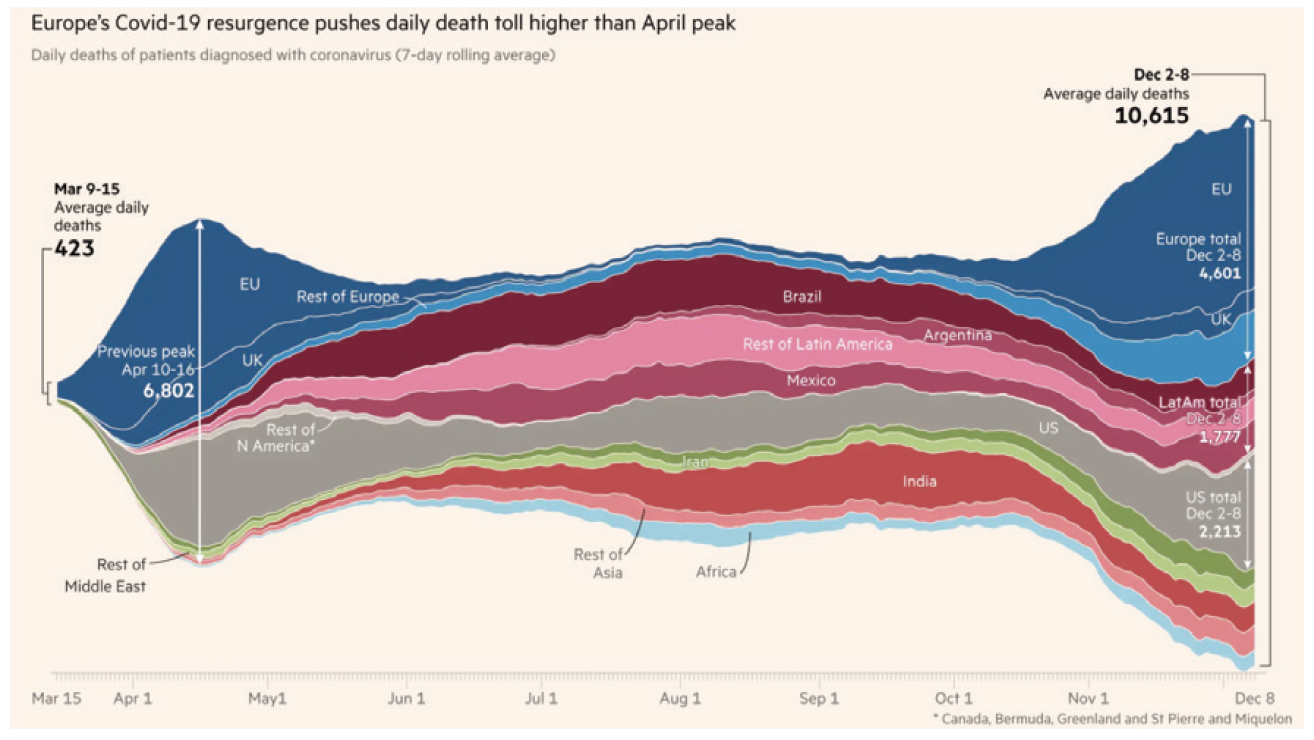

More focus on data and visual storytelling formats. Both the pandemic and US elections demonstrated the value of news organisations that could visualise and explain complex stories in an accessible way. The Washington Post’s coronavirus simulator5 was its most viewed story ever and helped make the case for the establishment of a new department of seven journalists which will start this year. Data journalism frequently breaks away from the traditional narrative, offering many pathways to explain and explore the news. Other publishers are looking to develop more visual content such as the stories format now adopted by most social platforms.

Case for public media becomes stronger. Heavy usage of public broadcasters and their websites during the pandemic may have made it harder for critics to undermine existing funding models – a recurrent theme in many European countries. The UK government is set to shelve plans to decriminalise the license fee, a move that may have cost the BBC $1billion over five years. More widely, politicians may need to rethink their attacks on the ‘fake news media’ after discovering how much they have relied on trusted channels to reach beyond their own support. But this could just be wishful thinking. With Joe Biden in the White House we can, at least, expect a less antagonistic relationship over the next few years.

1.3. Accelerating the shift to paid content

One of the key trends we highlighted in last year’s predictions report was the push towards digital subscription and other forms of reader payment. Covid-19 has given a big boost to that trend, with subscription specialist Zuora reporting that media publishing was the second fastest growing segment – after video streaming services such as Disney+, Netflix, and Amazon Prime. Average subscriptions across news, according to Zuora, were around 110% higher than the year before, when comparing the months March to May 2020.6

The New York Times alone has added more than a million net digital subscribers in 2020 – citing unprecedented demand for quality, original, independent journalism7 – and the Swedish publisher Dagens Nyheter offered open access to its website and apps for the first few months of the Covid-19 outbreak in return for an email address – subsequently converting record numbers to boost its subscriber base by a third.8 In the United Kingdom, the Guardian has been another beneficiary of the so-called ‘Covid bump’. It now has over a million regular subscribers and ongoing contributions – with subs for its paid-for apps growing 60%.9

But our Digital News Report 2020 also showed that, when it comes to reader payment, it tends to be a few big national and international brands that take the lion’s share of the spoils in a ‘winner takes most’ environment. As one example, the Washington Post plans to add 150 new jobs in 2021, creating a newsroom of more than 1,000,10 while medium-sized and local media have often been left with staffing that is stripped to the bone.

For many of the early movers, digital revenue now outstrips print and a significant number of quality titles can see a path to a sustainable future. But so too can a large number of smaller digital-born publishers with significant reader revenues, like the Daily Maverick in South Africa, Dennik N in Slovakia, El Diario in Spain, Malaysiakini in Malaysia, MediaPart in France, and Zetland in Denmark. Many of these publications have been successful by relentlessly focusing on meeting specific audience needs: ‘Willingness to pay for news does not exist I’d argue’, says Lea Korsgaard, Editor-in-Chief at Zetland, ‘but willingness to pay for convenience, news explained by people I like and feel a connection to, and a sense of belonging does exist’.

Can subscription models eventually work for all or just for a select number of high-quality titles? Our survey of industry leaders suggested a divided view, with half (51%) optimistic and four in ten (41%) taking a more sceptical view.

More medium-sized and smaller publications have started asking for subscriptions or reader contributions in the last 12 months and, even in countries that have not had much tradition of charging for online news, the position has started to change: ‘We have increased our number of digital subscriptions by more than 50% in the last year and we are counting on a 25% to 30% increase [in 2021]’, says Francisco Balsemão, CEO of the Impresa Group in Portugal which operates the Expresso newspaper and the SIC news brand. But for many publishers, growth in digital subscriptions won’t be nearly enough to compensate for the substantial falls in print circulation – as well as print and digital advertising revenue.

The full impact of the financial hit caused by lockdown is being felt now. No new investments, no new plans. The effort is to hold on and consolidate.

Dwaipayan Bose, Editor, Indiatoday.in

While a number of publishers are doing well, a large number of titles are clearly struggling and we can expect further consolidation, cost-cutting, and closures in the year ahead.

What else will happen this year?

Retaining subscribers. A burning question will be how to keep all those new subscribers who came on board during the Covid bump? ‘We are very focused on retaining these new readers into the future’, says Rebecca Costello, CEO at Schwartz Media in Australia. With more publishers chasing a relatively small number of consumers prepared to pay, this could become even tougher as the economy worsens and personal finances get tight. Cut-price offers and differential pricing are two likely outcomes. Publishers like the Wall Street Journal already have special ‘save deals’ for those who’ve lost their job.11 Expect more cheap deals for students and those from disadvantaged backgrounds as a way of countering critiques about growing information inequality.

More platform support for subscriptions. This is already under way (e.g. Apple News+, Subscribe with Google, and Substack for independent writers) but we can expect more seamless integration of subscription into a wider range of native platform experiences this year. Podcasts is one area where there is scope for integration – opening up possibilities for publishers to create bundled print and audio subscriptions.

1.4. Revenue diversification: e-commerce and live events

The Covid shock has reinforced a view that the industry needs to break an unhealthy dependence on digital advertising, which is blamed amongst other things for encouraging clickbait, reducing quality, and creating a poor user experience. On the business side, publishers have struggled in the face of intense competition from platforms – with Google and Facebook taking the lion’s share of growth. Now Amazon is stepping up its focus and is expected to account for more than 10% of the market next year, even as many news publishers see little or no growth in their online advertising revenues.12

Many argue that sustainable independent media require a different approach supported by multiple revenue streams. Our survey reflects this shift, with respondents indicating more attention on subscription and less emphasis on advertising since we last asked this question in 2018. It also shows how important diversification has become, with commercial publishers citing, on average, four different revenue streams as being important or very important to them this year.

These mixed or hybrid models are beginning to produce positive results. The Independent in the UK, which ditched its print edition more than four years ago, combines digital advertising, e-commerce, affiliate revenue, premium subscription, and a contributions model. It has also been expanding into other languages such as Spanish. ‘We have come through the year with record profit and record revenue, so we’re very confident of the year ahead’, says Managing Director Christian Broughton. The Independent has plans to accelerate new initiatives this year – including a new video/TV proposition and more international expansion, targeting rapid revenue growth.

What can we expect in the year ahead?

There is no silver bullet or single solution to the revenue conundrum but here are some areas of potential growth.

Publishers start to look more like retailers in 2021. Globally, spending on e-commerce is predicted to double over the next four years to $7 trillion according to GroupM.13 Covid-19 has driven a sharp uptick in online shopping, with its share rising to 35% of all retail in the UK in 2020 – up from 20% a year before. Publishers are increasingly thinking about how they can get a chunk of this growth by curating content that creates the right intent to buy. Stand-alone review sites like Wirecutter from the New York Times, the Strategist from New York Magazine/Vox Media, and IndyBest from the Independent are just a few examples of successful sites making significant contributions to the bottom line from affiliate revenue – with the additional benefit of collecting valuable first-party data.

Other publishers are looking to create new content verticals that can take advantage of the e-shopping boom. BuzzFeed, for example, has created its own range of branded cooking products linked to its popular Tasty Brand. Early in 2021 BuzzFeed will be creating a Sex and Wellness vertical aimed at a GenZ and millennial audience and has already created the first of a range of sex toys.14

Publishers as e-tailers

Recommendations

Physical goods

BuzzFeed’s acquisition of HuffPost, one of the media stories of 2020, will provide an even bigger storefront for its e-commerce ambitions, especially around topics which play well with younger audiences.

Selling other people’s subscriptions. Publishers may also be able to benefit from the wider subscription trend which encompasses everything from music, entertainment, and learning to fitness, flowers, and food. Apple and other tech companies have been taking a cut of ongoing subscriptions for years but news organisations with scale and good data targeting may also be in a position to help retailers find the right customers. Yahoo is one company that already offers special deals for Netflix and Peloton, handling the billing too, which helps increase the margins.

Live events and community. Covid-19 has required publisher event strategies to be rapidly rewritten with physical get togethers cancelled and activity moving online. Rapid consumer adoption of online tools like Zoom, Houseparty, and Google Meet have opened up new opportunities in both the B2B and B2C sectors. During the pandemic millions tuned into live concerts, fashion shows, and inspirational talks. Meanwhile publishers have found that virtual events can be spun-up more quickly, with a lower cost base, higher profile guests, and a bigger audience than a physical event. The Economist has been one news organisation experimenting with free and paid models with open Q&As with its writers, while 27,000 readers tuned in for a subscriber-only live interview with Bill Gates.

Virtual events boomed during the pandemic

Either way we can expect to see greater professionalisation around the production and packaging of these events – as well as new features that help deliver more compelling online experiences. Some Zoom fatigue will be inevitable in 2021 as our craving for human contact is rekindled, but as with so many other areas, the future is a likely to be a hybrid one.

1.5. Innovation: pandemic sparks more radical experimentation

One consequence of the pandemic has been rapid innovation, as news organisations found new ways of remaking existing products or created entirely new ones in the face of changed demand. Companies have been forced to think outside the box on a range of issues, from online working to developing new formats. ‘We were able to move much faster and ignore bureaucracy … so we were able to push things forward’, says Alina Fichter, Head of Digital Format Development at Deutsche Welle. Others point to examples of emboldened decision-making, with CNN launching its coronavirus podcast in just a few days – a process that might previously have required months of analysis and a long series of meetings.16

The increasing role of audience insight and data (74%) in driving innovation is highlighted in our survey – along with the importance of multi-disciplinary teams (68%) working to break down silos. Even senior leaders polled for this report recognise that their contribution is now less about generating new ideas (26%) and more about facilitating others – in a process informed by data.

The pace of innovation will remain strong this year as media companies accelerate their digital plans. But with little money available for big new investments, companies are likely to focus on improvements to existing products and brands (70%) rather than developing ‘moonshots’ or creating entirely new products (28%). Many of our respondents said that the pandemic hadn’t changed their view of existing strategies – but they have needed to move faster because of it.

What can we expect this year?

Better user experience and design. Many of our survey respondents felt this was the year to put more emphasis on the core experience of websites and apps themselves, which increasingly lags behind consumer expectations. ‘Publishing in general has a lot of basic catching up to do on ease of use, customer service, etc.’, said one publisher that has been involved in subscriptions for many years. ‘The benchmark is Amazon and Netflix. It’s no use having AI recommendations if people can’t easily log in, pause subscriptions, or change billing details.’ Others point to poor user experience overall and the need to focus more on interaction and visual design: ‘We believe that design has great potential to improve user experience, engagement, and subscriber lifecycle’, notes Goetz Hamann, Head of Digital Editions at Die Zeit. ‘News organisations have to learn from digital pure plays and the consumer industry how to add value through design.’

Focus on sustainable innovation. The stresses of coronavirus have left many burnt out by the rate of change. It can be easier to start new things in the heat of a crisis but harder to close them down. For some publishers, this means finding better ways to manage and coordinate the process: ‘Innovation will need to be constant so creating a framework for continuous change is paramount’, argues Styli Charalambous, CEO of the Daily Maverick in South Africa. In this respect, our survey confirms the importance of ‘translation roles’ such as the product manager – a job title imported from Silicon Valley – which takes a lead in shaping new initiatives and orchestrating agile delivery.

More than nine in ten (93%) now recognise the importance of this role, but many feel that those doing the job often lack the right skills (54%) and less than half think it is well understood (43%).

For many media companies managing innovation remains a difficult and frustrating process. Finding ways to break down silos and get the best out of multi-disciplinary teams will be critical as publishers look to add agility. Product managers help bring an evidence-based approach to the process of deciding which opportunities to pursue and a user-centred approach to delivery. ‘Product will drive the industry because we need to have the customer at the centre of everything’, says Luciana Cardoso, Chief Product Owner at Estadão newspaper in Brazil. ‘I once heard content is king, but product is queen, and I really agree with that.’17 The creation of an international News Product Alliance this year is a much-needed initiative aimed at raising the role’s profile across the industry.18

For years news organisations have talked about the need for a ‘level playing field’ with giant tech platforms and have argued for a fairer reward for the content that they say helps those companies grow and thrive. With some publishers set to receive significant pay-outs could this be the year when at least some publishers’ dreams come true? Or are we in danger of setting up a new and unhealthy dependence?

2.1. Extending platform payments for news

Increased payment by platforms for some news content is set to be one of the biggest media stories of the year. Facebook’s news tab, which launched last year in the United States, is coming to the UK in January and to Germany, France, India, and Brazil at some point in 2021. In the US this has involved paying some large publishers millions of dollars,19 though critics say that many smaller news organisations have been left out.20

Meanwhile Google has said it will collectively pay around $1 billion to partner news publishers globally in licensing fees over the next three years ‘to create and curate high-quality content’ for new story panels called Google News Showcase that will appear on Google News and other services. These have already rolled out in Germany and Brazil with plans to expand to other markets. In some cases, Google is also offering to pay for free access for its users to read paywalled articles on a publisher’s site – opening up more opportunities for growth for those who join. This model is different to that operated by Apple News which licenses both premium and free content as part of its Apple News/Apple News+ service in the US, Canada, Australia, and the UK.

Content licensing and content curation by platforms

Beyond big technology companies’ own initiatives, which some see as at least in part motivated by the desire to stave off possible regulatory intervention by satisfying key publishers, some countries have seen politically driven developments. In France, after protracted negotiations, Google has agreed a new deal reportedly paying French publishers about €30m annually for an initial three-year period, licensing content specifically to Google’s News Showcase product.21 This is a step forward for the publishers in question, though significantly less than the €150 million a year that the publishers originally demanded, and it amounts to well under 3% of the annual revenues of French legacy news publishers.

In Australia new legislation has been tabled to force Google and Facebook to negotiate payment for using publisher content.22 In the opening rounds of protracted discussions, Nine Entertainment, which owns mastheads including the Sydney Morning Herald, said it would expect news publishers to receive A$600 million a year from Facebook and Google if a mandatory bargaining code were to be introduced. News Corp suggested the figure could be A$1 billion a year.23 The big technology companies have disputed these figures and lobbied hard, first against the proposed law and later to ensure the legislation recognised the monetary value platforms provided to news businesses by directing readers to their websites.24 The outcome will be watched closely by publishers across the world.

The wider implications of all this activity on news consumption are not yet clear. Separating quality news content into tabs or apps might be good PR, but will casual users ever go there or will they instead stick to the newsfeed and organic search? Then again, if these aggregations do prove successful, they could end up taking traffic away from publishers’ apps and websites – undermining long-term sustainability.

What could happen this year?

Publisher solidarity comes under strain. As the deals become clear, we can expect more arguments between publishers over the criteria for selection of brands to be included and over the promotion of content by platforms. In the Australian negotiations, News Corp argued that original content should be favoured while the Daily Mail suggested that the issue of ‘quality’ is too subjective.25 In both France and Australia arguments have taken place over whether public broadcasters and digital-born brands should be part of these schemes. In our survey, around half (48%) feel that the money should go to a small number of publishers based on quality while a third (32%) feel it should be more evenly spread – based more on what people read and enjoy.

This chart clearly illustrates that publishers still have very different views on how to deal with platforms. This is not surprising given the growing divergence of both strategies and business models, but it does also suggest that a united front will be hard to maintain across 2021 and beyond.26

2.2 Additional platform support versus more self-reliance?

Beyond commercial deals, the Google News Initiative (GNI) and Facebook Journalism Project (FJP) have each contributed hundreds of millions of dollars to help journalism over the last few years. These programmes include product initiatives, innovation funding, and support for independent research.27 In response to the coronavirus outbreak, Facebook and Google have committed an additional $212 million to nearly 7,000 local newsrooms and fact-checking initiatives, according to analysis from the Tow Center.28

The threat to human life has also prompted platforms to take a more robust approach to removing misleading content in the last year. Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube removed posts shared by Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro for including coronavirus misinformation that violated their rules on harmful content. Twitter flagged around a third of Donald Trump’s posts after the November election as false, as he continued to argue that he won the contest – but did not remove them entirely.

Despite these initiatives, news organisations continue to rate platforms poorly when asked about their support for journalism overall. Only a third of our respondents rated Facebook and Twitter between 3 and 5 on a five-point scale that measured their commitment to journalism, with even lower scores for Apple, Snapchat, and Amazon. Only Google saw more than half of publishers (59%) rating their support as either average or good. Scores were similar to last year, with the exception of Facebook which showed an improvement of eight percentage points.

What more could platforms do?

Beyond providing more ‘no strings money’, publishers have a range of requests. Some would like platforms to take a more proactive approach to prioritising reliable news and original journalism. ‘Much of the work done to date is preventative. We are here and working in the business of information and we should be promoted as such’, argues Beth Ashton, Audience Editor at the Independent. Others highlight the need for tougher action on hate speech and misinformation, with more funding for fact-checking and misinformation initiatives across multiple platforms. Subscription publishers have a series of requests including removing friction points to payment and helping news organisations tap into platform data about an individual’s propensity to pay. This could help publishers to target their marketing spend and operate more effective dynamic paywalls.

Publishers continue to request richer data about how their content is performing and more timely information about product changes: ‘They should be much more transparent with their algorithms and communicate changes better to allow media to respond and develop better strategies’, says Christina Elmer, Deputy Head of Editorial Development at Der Spiegel. Others recognise the value of funding of news literacy and innovation but would like longer term commitments in these areas.

How can publishers help themselves?

Some argue that, instead of waiting for handouts from platforms, publishers need to focus much more on putting their own house in order. ‘A platform will always build in incentives that reward quantity more than quality’, argues Jan-Willem Sanders, publisher and co-owner of the investigative news site Follow the Money in the Netherlands. ‘The challenge for publishers is therefore to create a product that is attractive enough that the public will want to read, listen, or watch it at the source.’ For years many news publishers have suffered from slow ad-heavy websites and inconvenient ways of buying inventory. The Washington Post is one company that is trying to change that with its own ad tech (Zeus Performance) which aims to improve speed of websites and the viewability of advertisements. Other initiatives like Vox’s Concert platform and The Ozone project in the UK aim to provide an easier way for advertisers to reach quality audiences across a range of publisher content.

These alliances are becoming more critical at a time when publishers are still working through the implications of the demise of the third-party cookie, which is making it harder for advertisers to track and target their digital media spend. Google’s Chrome browser will phase out cookies over the next year or so, and Apple will only allow access to consented users’ IDFAs (Identity for Advertisers) from early 2021 – changes driven by consumer concerns about privacy. In response publishers will need to build up as much first-party data as possible, which is why we’ll be subjected to messages asking us to register before accessing content this year.

2.3 Regulation and the Role of Government

Apart from, in some cases, perhaps pressuring platforms to pay some news organisations for content, many governments will be advancing plans to legislate on aspects of online activity.

In the UK we’ll see new obligations for business around preventing online harms, which will cover everything from terrorism to child abuse and self-harm. This will also involve a new regulator to oversee this complex area. Across Europe, platforms will face greater scrutiny from competition authorities limiting their ability to give preference to their own services, and leverage user data across different business areas. In the United States, both Facebook and Google face anti-trust charges from the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice, respectively.

In terms of journalism, governments and regulators will be closely monitoring the economic impact of Covid-19 on the provision of both national and local news titles. Tax relief on digital subscriptions has been a significant boost for many publishers and has now been applied in many countries, including the UK,29 but there will also be pressure to implement more of the recommendations of the Cairncross Review, such as direct government support for public interest journalism and new institutions.30 Meanwhile we can expect continuing controversy over so-called ‘fake news’ laws, which have been introduced in many countries over the last few years. In Hungary the authorities can now jail people for up to five years for ‘distorting’ facts relating to the coronavirus. Critics say further tightening of the rules is anti-democratic and is intended to silence opponents of the Prime Minister Viktor Orbán.

Taken together these changes are likely to mark a significant new phase for the internet, with more regulation in general, more limits on free speech, and more protection for consumer rights. Not all of these changes will necessarily be in the interests of all publishers. Despite this, our digital leaders are markedly more positive about government intervention this year. More than a third (36%) think policy changes could help journalism, compared with just 18% last year. The number that worried about perhaps unintended consequences hurting journalism fell from 25% to 17%.

This change in sentiment could reflect confidence that governments are finally prepared to take bolder action to help publishers, as well as rising concern about the impact on journalism of unchecked conspiracy theories and other forms of misinformation.

The pandemic has come at a time when the cohesion of societies is increasingly under strain from rapid economic and technological change. Rising populism, protests over social injustice and inequality, falling trust in institutions, and the rise of conspiracy theories are some of the symptoms – and these have created a new set of circumstances for journalists to navigate.

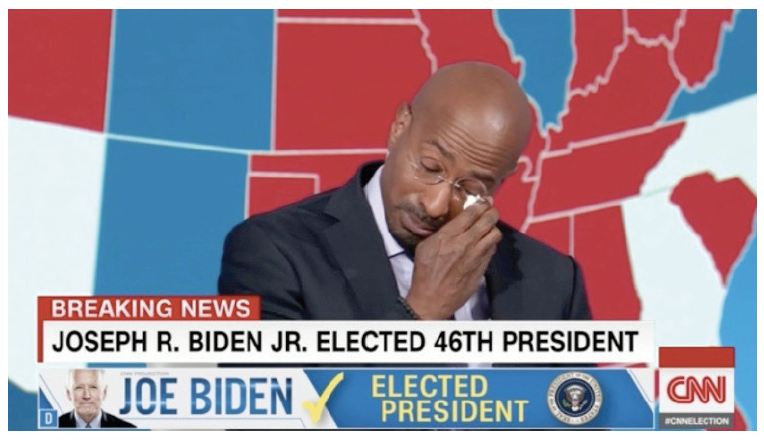

Does a traditional approach of dispassionately airing all the arguments and leaving it up to people to make their own judgement still stand? Or does this risk giving undue weight to extreme positions and help amplify lies? Should journalists take a clear moral stand in their reporting of, for example, the killing of George Floyd, the ‘climate emergency’, or the attempted subverting of a presidential election? Should journalists express their feelings openly rather than keep up a pretence of neutrality? Or does it depend on different media traditions, formats, and expectations?

CNN host Van Jones received many plaudits on social media for a powerful monologue on election night, while US TV networks cut away from a live press conference where President Trump was repeating unsubstantiated allegations about electoral fraud. In the UK, BBC host Emily Maitlis was found to have breached the corporation’s guidelines on ‘due impartiality’ when she declared that the prime minister’s adviser, Dominic Cummings had broken lockdown rules and made ordinary people ‘feel like fools’.

TV anchors taking a stand in 2020

These are complicated questions that are hard to capture in a couple of survey questions but these issues will be increasingly discussed in newsrooms this year. Our sample of news executives, which includes many senior editors, is clear that impartiality matters more than ever (88%) but many also recognise (48%) that there are some issues (democracy, racism) where it is not appropriate for journalists to take a neutral position. We’ll be exploring the nuances of these issues in more detailed research with consumers later this year.

What might happen this year?

Reimagining impartiality. Some media companies like the BBC are doubling down on impartiality, reissuing guidelines to take account of changed circumstances. The new Director General of the BBC, Tim Davie, has placed impartiality at the heart of his vision for the BBC and plans to crack down on staff expressing opinions on social media. Others will be looking again at whether it can be counter-productive for staff to engage via social platforms. But this will not be straightforward. Our Digital News Report research shows that, while people in most countries still favour the ideal of a neutral and objective journalism, a larger minority of younger people say they prefer news that shares their point view – and they expect to engage with the news on social platforms too.31

Rise of partisan online video? The US election has seen a resurgence of partisan networks like Newsmax and America One, increasingly now distributed online via portals and via YouTube and Facebook. These opinion-led channels are set to come to the UK this year in the shape of GB News, a new TV channel aimed at ‘British people who feel underserved and unheard by the media’,32 and also a new online TV venture from Rupert Murdoch. Meanwhile many talk-radio channels have increasingly moved to a hybrid audio/video format distributed via YouTube and social media. Any new UK television channels will be subject to regulation by Ofcom which requires some balance of political views within the network – but impartiality rules do not apply to online video. Better tools and backdrops have made it easier to create professional-looking news commentary with a growing range of options for distribution and monetisation than ever. Spotify’s addition of video podcasts could supercharge partisan news still further.

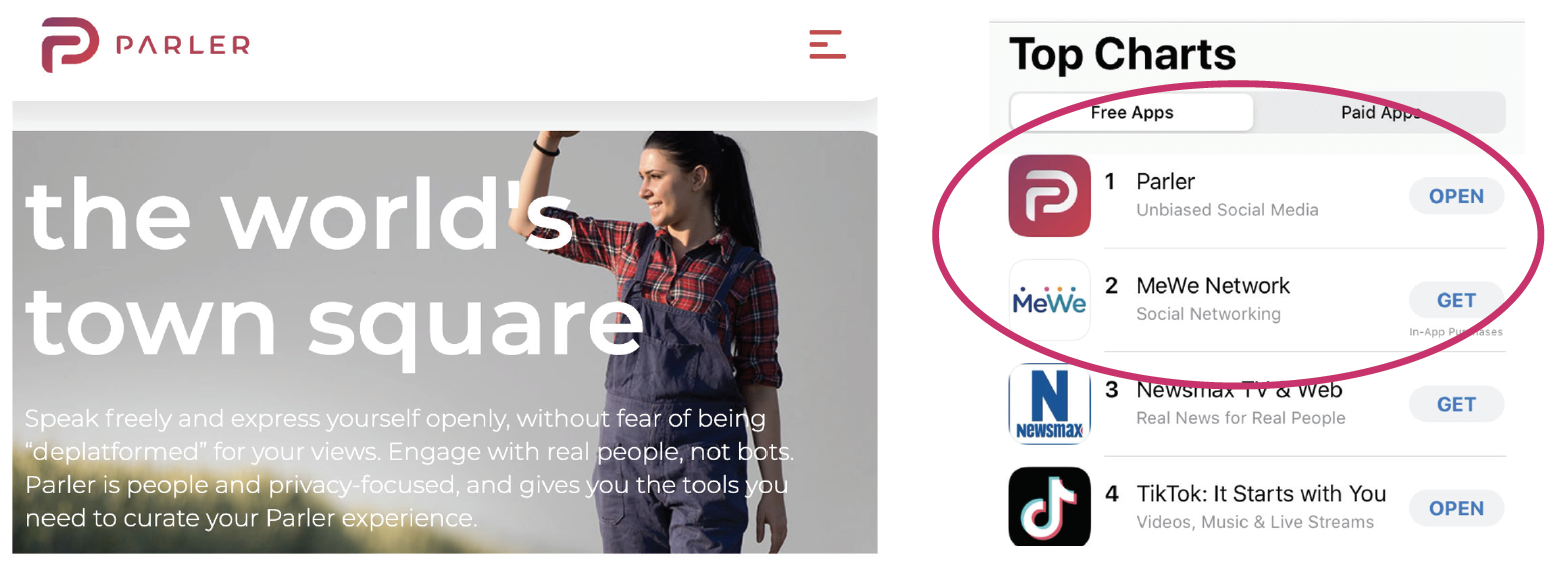

Partisan social networks. As the big tech companies continue to clamp down on misinformation expect more claims from Republicans and Conservatives that they are being censored by a liberal elite. One beneficiary is likely to be Parler, a Twitter-like app that describes itself as the world’s ‘premier free speech social network’, and other sites like MeWe and Rumble, which have specifically welcomed conservatives. But in these divided times, these networks may struggle to avoid the fate of Gab, which became a haven for extremists including neo-Nazis and white supremacists.

Parler and MeWe amongst most downloaded apps in US Apple store – November 2020

Emails and podcasts are not exactly new technologies but these resurgent formats are encouraging a flourishing of independent and entrepreneurial journalism. At the same time, they have become key tools for traditional media companies to engage audiences more deeply and more directly. Major journalistic hires – such as Ezra Klein and Kara Swisher by the New York Times – may increasingly be based on mastery of one or other of these skills:

4.1. Email fuels entrepreneurial journalism

2020 was dubbed the ‘year of the newsletter’, with a host of high-profile writers leaving traditional jobs to set up their own businesses, mostly based on email. Amid the uncertainty of the pandemic, many were enticed by the promise made by new platforms like Substack, TinyLetter, Lede, or Ghost which offered direct control for writers and potential rewards running into millions of dollars.33 Casey Newton (formerly of The Verge), Alex Kantrowitz (formerly of BuzzFeed), and Andrew Sullivan (formerly of New York Magazine) are just some of the – mainly white, male, and already well-established – entrepreneurial journalists who made the switch.

This trend echoes the start of the blogging revolution over a decade ago, which also gave authors freedom to write on topics they were passionate about without the constraints of a traditional newsroom. The difference is that these new platforms are geared around subscription rather than advertising, which encourages a quality-based approach to content that may prove more sustainable. Based on average charges of between $60 and $100, a list of just 1,000 subscribers can produce a comfortable income – with anything beyond that often well in excess of a traditional salary.

At the same time, mainstream media have also been increasingly turning to email to support engagement strategies. Data insights consistently show that signing up for a relevant newsletter is the best way to reduce churn for existing subscribers or develop a new relationship with potential customers.

More money in newsletters for 2021

Big media companies have also recognised the move toward ‘journalist-led’ emails in the last year, encouraging talented writers to start or develop their own channels even if that means de-prioritising other elements of their work. The New York Times now runs over 70 newsletters and recently appointed senior journalist David Leonhardt as anchor of the morning briefing newsletter, which it also revealed has more than 17 million subscribers. The use of the term ‘anchor’, a term borrowed from network TV, shows the value now placed on human curation, on guiding audiences through the news of the day.

What will happen this year?

Newsletter backlash? This may be the year when consumers struggle to get through the large number of emails they’ve signed up to during the lockdown. At the same time, some writers will struggle with the pressure of having to come up with the goods day after day. We may see some high-profile defections back to mainstream media, where there is potentially more variety and more editing and legal support. Platforms like Substack may also struggle to show that they can showcase and reward new and diverse voices alongside proven writers on a narrow range of subjects.

4.2. Podcasts and audio

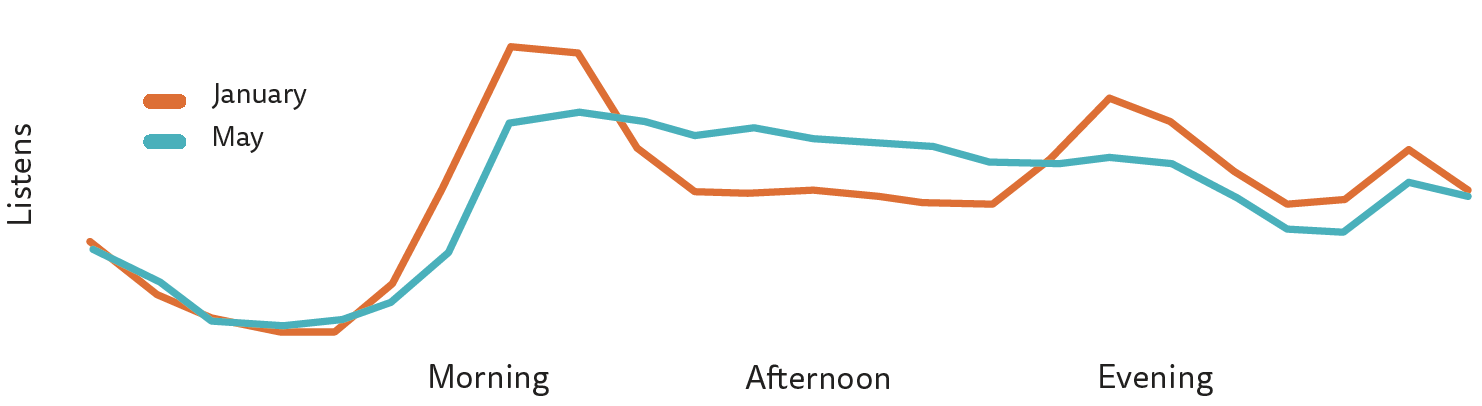

Podcasts continue to go from strength to strength, despite the pandemic putting paid to the morning commute – one of the most popular times of day for listening. As we revealed in our most recent report on the subject, news podcasts grew strongly through 2020, outstripped as a genre only by comedy.34

Coronavirus flattens the peak

Listening times in UK Jan-May

Source: Acast. Based on aggregated data from news podcasts in the UK.

Our report also identified more than 100 native daily news podcasts across six countries, many inspired by The Daily from the New York Times, which now gets around 4 million listeners a day, a figure which CEO Meredith Kopit Levien says is ‘almost twice as large as the paper was at its peak’.35

Pop-up podcasts relating to the pandemic like Coronavirus Fact vs Fiction (CNN), Coronacast (Australian Broadcasting Corporation), and Coronavirus Update (NDR, Germany) have also proved a hit with audiences around the world.

The year also saw major developments on the platform side, with Amazon pushing further into podcasts and Spotify outstripping Apple as the number one platform in a number of markets. We’re already seeing big platforms looking to directly control the production as well as distribution of podcasts. 2021 has begun with Amazon’s acquisition of Wondery, one of the last independent podcast publishers left standing. Spotify has already acquired Gimlet Media, Anchor, and Parcast – and most recently The Ringer (sports) and Megaphone. Podcasting is starting to look like a version of the video-on-demand streaming wars with similar dynamics at play.

What will happen this year?

Battle for the stars. Expect to see platforms try to sign up more of the world’s top talent on exclusive contracts this year. Spotify has led the way paying a reputed $100m for The Joe Rogan Experience, one of the most popular podcasts in the US. It has also struck deals with Prince Harry and Meghan and former First Lady Michelle Obama. Meanwhile Amazon has secured celebrity contracts with the likes of Will Smith and DJ Khaled. Expect Apple to push into exclusive content as it tries to shore up its position and the BBC is one broadcaster looking to strengthen its audio app, BBC Sounds, by commissioning more highly rated podcasts from stars such as George the Poet and James Acaster.

Paid models strengthen. Deloitte estimates that the podcast market could exceed $3.3bn globally by 2025 – about three times its current size (though still a small fraction of the news industry overall). Much of this will continue to come via advertising but we’ll also see a significant shift to paid models in 2021. Apart from platform payments at the top end, there’ll be opportunities to sell direct subscriptions via existing podcast apps and new players like Substack that are looking to extend the independent journalist model to audio. Contribution and donation models are supported by a range of platforms including Patreon.

The year of video podcasts. These have been around for a while but the success of Joe Rogan has pushed many other creators to film shows and attract a whole new audience. Spotify’s adoption of the format is set to further drive this format along with the growing popularity of screen-based smart speakers. Broadcasters have also been experimenting with dual-use podcasts such as the BBC’s Newscast and Americast which are both also shown on TV. Publishers like Vox have found success in turning audio ideas into video by either developing them at the same time or sequentially. One recent example is a recent series of technology histories of the rise of tech companies (The Land of the Giants), which is now being developed for TV: ‘We can test out an idea in podcast form or video and that will lead to us developing it out for television’, says Vox publisher Melissa Bell.36

New York Times explores long form. The publisher is also betting heavily on audio having acquired Serial Productions, the company behind hit podcasts Serial and S-Town, for around $25m as well as Audm, a start-up that is focused on showcasing long-form journalism. The Times has moved strategically into audio and visual storytelling in recent years and we can expect the company to use these acquisitions to push further into long form and documentaries. Audio versions of written articles have already featured in The Daily and we can expect this trend to grow this year across a range of publishers.

In this final section we explore some of the technologies that are likely to influence all our lives over the next decade. But how will the development of artificial intelligence (AI), augmented reality (AR), 5G connectivity, and smart devices affect journalism?

5.1. Artificial intelligence gets real

Our survey shows that publishers see AI as the biggest enabler for journalism over the next few years. Over two-thirds (69%) named AI compared with around one in five (18%) who voted for benefits of faster 5G connectivity and one in ten (9%) who felt that new devices would have the biggest impact.

Media companies have increasingly been getting to grips with AI technologies such as machine learning (ML), natural language generation (NLG), and speech recognition to help find new stories and customers, speed up production, and improve distribution. Much of this activity has been documented by the Journalism AI project from the POLIS think tank at the LSE which has been sharing best practice examples through the year.37

AI in action

While some are embracing the new technologies, others worry that AI could exacerbate the gap between giant media companies and the rest. Many smaller news organisations don’t have the money to invest in long-term R&D or pay for data scientists and fear being left behind. It may be possible to buy AI solutions off the shelf in the future, but these may be less tailored to the business and the costs are likely to be high. The majority of our respondents (65%) feel that big publishers will end up benefiting most.

What might happen this year?

Automation of multi-media formats from text. One of the most interesting areas to watch this year could be the automation or semi-automation of new formats from text. The BBC is experimenting with tools that turn a text news story into a ‘visual story’ suitable for mobile phones with pull quotes and animations. This may help media companies satisfy different format preferences between young and old without breaking the bank. Others are looking at offering summarised options of the news as an alternative to the full narrative article and more publishers are planning to add audio versions of their stories this year using a range of synthetic voices. Next-generation object-based content management systems such as Arc from the Washington Post and Optimo, which is being rolled out at the BBC, are set to provide this flexibility.

Automation of new languages. Advances in machine learning have driven improvements to automated translation, including neural models that have enabled high-quality translations in over 100 languages. Increasingly these are now integrated into audience applications allowing social media posts and news articles to be instantly translated. Expect to see more news organisations take advantage of these advances this year, offering foreign-language versions of text, audio, and video output at minimal cost. But AI support for smaller languages with less commercial potential continues to lag behind.

Downsides of AI become more apparent. The past year has seen a number of widely circulated so-called ‘deep fake’ videos, mostly trying to entertain rather than deceive. Channel 4 created a likeness of the Queen to deliver an ‘alternative’ Christmas message, wearing a coronavirus-shaped brooch, and making jokes about members of her family. The AI company Synthesis released a ‘deep fake Santa’ that delivered personalised greetings. Meanwhile YouTube is awash with video and audio fakes, including famous rappers reciting Shakespeare and the Bible, based on an AI programme that learns from hours of examples of their voice. For now, few people have been fooled and so-called ‘shallow fakes’, that include misleadingly edited or slowed down videos, remain a bigger problem. But with technology moving at a rapid pace, fakery of various kinds will pose a greater threat in 2021 and beyond.

5.2. Faster 5G networks and new devices

5G networks can transfer data dozens of times faster than the fourth-generation networks we use today. This will enable quicker browsing and high-quality video streaming, but 5G is not just another generation of wireless connectivity, it will make it possible to connect more devices at the same time, providing the backbone for the smart homes, smart cities, and autonomous vehicles of the future.

The number of 5G enabled smartphones is expected to more than double to 600 million in 2021, according to Strategy Analytics, though coverage will still be patchy in many countries and mainstream adoption is taking longer than many had hoped.

For news organisations, 5G will eventually enable reliable high-definition mobile reporting and make it easier to work and package media from any location. For consumers, 5G will bring benefits to applications like video livestreaming, gaming, and immersive technologies like virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR). Faster speeds and better screens will also accelerate the push to personalised news, mobile formats and more visual journalism.

Beyond the smartphone, a range of objects equipped with sensors and always-on internet connectivity (Internet of Things) will help us live smarter lives – but also potentially bring new dependence on big tech.

What can we expect this year?

Health-focused wearables. The pandemic has made us more conscious of our heath than ever and this is helping drive new sales. The Fitbit Sense added an electrodermal sensor – used by psychologists to identify stress levels, while the Apple Watch Series 6 added a blood-oxygen sensor to detect saturation levels. According to a recent Gartner report, consumer spending on wearable technology is set to reach $63bn in 2021, more than twice the figure in 2018.43 With smart watches and fitness accessories leading the charge, perhaps it is time for news organisations to take another look at developing snackable formats for these wrist-based platforms?

Boom for hearables. Apple AirPods have been an unexpected success and now make up the fastest-growing segment of the world’s most valuable company. Apple was estimated to have shipped over 80 million units in 2020, with other manufacturers of true wireless earbuds reporting record sales. New features on the way this year include functionality that adjust sound levels depending on the context or location, and allow control by gesture as well as voice. The popularity of hearables will further the importance of audio formats such as podcasts and human-read stories.

Smart speakers. Growth of these voice-driven devices is starting to slow despite falling prices and new devices. Google recently refreshed its Home range with new hardware and a new name – Nest Audio. Amazon’s Echo devices have also had an update while Apple introduced the long-awaited HomePod mini at just $99. This year expect more speakers to have screens to take advantage of the increasing amount of hybrid audio/video content, but also to help consumers more easily discover the range of options available. Stand-alone speakers may eventually disappear as the voice assistants inside get integrated into TVs, sound systems, and cars.

Smart glasses are back. Google Glass was widely felt to be ahead of its time, though it has since been reborn as an enterprise product. Snapchat’s Spectacles took a more playful approach with filters and 3D effects, but have not been a commercial success. Even so, there is much anticipation over Apple’s entry to the ‘extended reality’ market, with a major announcement expected in 2021, even if consumers have to wait at least another year to get their hands on it. Apple Glass is said to be able to display messages, emails, maps, and even news over the user’s field of vision, with interactions controlled via both buttons and gestures. This has been a long-term project for Apple but will need to overcome concerns over privacy, battery life and usability if it is to be a success.

The combination of new devices, better connectivity, and increasingly powerful technology holds out the promise of a smarter world where human intelligence is augmented and supported by machines. But it also marks another wave of rapid disruption with potential downsides for many, with much of the underlying technology developed and controlled by a small number of big technology companies. 2021 will not be an end-point in that journey but a year when more of the building blocks fall into place. Journalism’s job – as with the coronavirus crisis – will be to explain the implications for ordinary people, but also to ask searching questions about transparency, control, and how equally the spoils are being shared.

At the same time, journalism as a business will need to embrace this moment to complete its own transformation. The pandemic has comprehensively made the case for faster change towards an all-digital future. We’re already seeing the emergence of distributed newsrooms, taking advantage of collaborative online tools to get more reporters out of the office, and offering greater personal flexibility for staff. This will be the year when new hybrid models get road-tested and we try to find the right balance between efficiency and creativity. But newsrooms will also need to innovate in new digital formats if they are to successfully engage audiences on the platforms where they choose to consume the news. This will be a year when text-based newsrooms invest more heavily in online audio and video content, in data journalism, as well as the snackable visual ‘stories’ that work well on social media. For broadcasters, the challenge if anything is even greater, as audiences migrate at speed to digital streaming services and as other media companies shift resource into audio and video.

On the business side, subscription models have undoubtedly been boosted by coronavirus, but 2021 is likely to be a tough time to hold on to cash-strapped customers increasingly looking for diversion and entertainment – let alone find new ones. That’s why this year could be defined more by attempts to diversify revenue streams with e-commerce and events set to be the hottest areas of activity. Big companies with more cash in hand will be better placed to invest in these growth areas, increasing the ‘winner takes most’ dynamics that have been developing for some time. Platform payments to the largest news brands as part of their revamped news offerings could benefit some, but in the process further exacerbate inequalities and undermine plurality unless this is tempered somewhat by more platform and/or government support.

While some publishers are happy to take any money on offer, others remain extremely wary and are more determined than ever to focus on long-term sustainability. The key will be to create more engaging and relevant owned experiences and to develop a deeper connection with audiences. Digital in 2021 and beyond will no longer be about just websites and apps but increasingly about expressing journalism across multiple channels including emails, podcasts and online video. More direct engagement has the added benefit of attracting more first-party data which many see as the key to a sustainable future.

The shock of coronavirus has been a catalyst for much-needed change for journalism as for many other industries. In the coming year we’ll find out which new habits will stick and which will prove to have been temporary. We’ll also find out which publishers have the confidence and nerve to seize the new opportunities that have emerged.

234 people completed a closed survey in December 2020. Participants, drawn from 43 countries, were selected because they held senior positions (editorial, commercial, or product) in traditional or digital-born publishing companies and were responsible for aspects of digital or wider media strategy. The results reflect this strategic sample of select industry leaders, not a representative sample.

Typical job titles included Editor-in-Chief/Executive Editor, CEO, Managing Director, Head of Digital, Director of Product, and Head of Innovation. Over half of participants were from organisations with a print background (57%), around a fifth (22%) represented commercial or public service broadcasters, more than one in ten came from digital-born media (15%), and a further 8% from B2B companies or news agencies. The 43 countries and territories represented in the survey included Australia, New Zealand, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, Thailand, South Korea, Japan, Kenya, South Africa, Mexico, Brazil, Colombia, and Russia, but the majority came from the US, UK, or European countries such Germany, Spain, France, Austria, Finland, Norway, Denmark, and the Netherlands.

Participants filled out an online survey with specific questions around strategic digital intent in 2021. Around 95% answered most questions, although response rates vary. The majority (80%) contributed comments and ideas in open questions and some of these are quoted with permission in this document.

1 Reuters Institute, 'Changing newsrooms 2020'

2 The community news project is administered by the National Council for the Training of Journalists and employs more than 70 journalists at regional press titles. 'Facebook reporters bringing something new to newsrooms', Hold the Front Page

3 'Navigating the infodemic' Reuters Institute

4 The Sunday Times: ‘When Britain Sleepwalked into Disaster’, Tortoise Media, ‘Covid Inquiry’,

5 Washington Post Corona Simulator

6 Zuora.com, Subscription impact report

7 New York Times, earning release Q3 2020

8 WAN-IFRA, 'Webinar takeaways: How Dagens Nyheter has added thousands of digital subs during COVID-19'

9 Press Gazette, 'Guardian claims a record 1m paying readers after surge in regular contributions and subscriptions'

10 Press Gazette, 'Washington Post hiring journalists in London and Seoul as it plans to create new breaking-news hubs'

11 Press Gazette, 'Interview: How Wall Street Journal used subscriptions 'science' to sign up 350,000 new online subscribers this year' https://www.pressgazette.co.uk/interview-how-wall-street-journal-used-subscriptions-science-to-sign-up-350000-new-online-subscribers-this-year/

12 Business Insider, 'Google, Facebook, and Amazon will account for nearly two-thirds of total US digital ad spending this year'

13 Group M, ’This Year Next Year: E-Commerce Forecast‘ (Dec. 2020),

14 Digiday, 'BuzzFeed wants to become an authority of sexual wellness for millennials with a new branded sex toy'

15 FIPP, 'Events in Magazine Media'

16 Nic Newman and Nathan Gallo, 'Daily News Podcasts: Building New Habits in the Shadow of Coronavirus (Nov. 2020)', Reuters Institute.

17 Interview with News Product Alliance, Dec. 2020,

19 Wall Street Journal, 'Facebook Offers News Outlets Millions of Dollars a Year to License Content'

20 Press Gazette, 'Facebook News: US publishers happy with cash for content - but say project is a 'PR move''

21 Monday Note, 'Inside Google’s Deal with the French Media'

22 The Guardian, 'Australia is making Google and Facebook pay for news: what difference will the code make?'

23 Sydney Morning Herald, 'Payments negotiations with media companies unworkable, warns Google boss'

24 A factor that was included when the code went to parliament in December.

25 Press Gazette, 'Australian documents reveal how News Corp, Mail and other publishers plan to battle tech giants on global scale'

26 Rasmus Nielsen, Nieman Lab, 'Stop pretending publishers are a united front'

27 Full disclosure: the Google News Initiative helps fund some of the reports produced by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism including this Trends and Predictions report, and the Institute holds a large grant from the Facebook Journalism Project too.

28 Tow Center, 'Platforms and Publishers: The Great Pandemic Funding Push'

29 What's New in Publishing, '“Great news for publishers”: UK scraps tax on digital editions'

30 Department for Culture, Media and Sport, Cairncross Review

31 Reuters Institute 'Digital News Report 2020' and 'How Young People Consume News'

32 Daily Mail, 'Andrew Neil will lead new rolling news channel to rival BBC and Sky aiming to reach those who feel 'underserved and unheard' by the media'

34 Reuters Institute, 'Daily news podcasts: building new habits in the shadow of coronavirus'

35 Press Gazette, 'How The Daily podcast is helping the New York Times drive advertising and subscription growth'

36 Digiday, '"Using all parts of our business as innovation": Vox Media Publisher Melissa Bell on future content strategies'

37 LSE, JournalismAI

40 Reuters, 'Reuters applies AI technology to 100 years of archive video to enable faster discovery, supported by Google DNI'

43 Gartner press release 'Gartner Says Global End-User Spending on Wearable Devices to Total $52 Billion in 2020'

Nic Newman is Senior Research Associate at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, where he has been lead author of the annual Digital News Report since 2012. He is also a consultant on digital media, working actively with news companies on product, audience, and business strategies for digital transition. He has produced a media and journalism predictions report for the last 12 years. This is the sixth to be published by the Reuters Institute.

Nic was a founding member of the BBC News Website, leading international coverage as World Editor (1997–2001). As Head of Product Development (2001–10) he led digital teams, developing websites, mobile, and interactive TV applications for all BBC Journalism sites.

The author is grateful for the input of 234 digital leaders from 43 countries, who responded to a survey around the key challenges and opportunities in the year ahead.

Respondents included 52 Editors-in-Chief, 45 CEOs or Managing Directors, and 29 Heads of Digital and came from some of the world’s leading traditional media companies as well as digital-born organisations (see breakdown in the Survey Methodology).

Survey input and answers helped guide some of the themes in this report. Some direct quotes do not carry names or organisations, at the request of those contributors.

The author is particularly grateful to Rasmus Kleis Nielsen for his ideas and suggestions and to Alex Reid for input on the manuscript and keeping the publication on track.

As with many predictions reports there is a significant element of speculation, particularly around specifics and the paper should be read bearing this in mind. Having said that, any mistakes – factual or otherwise – should be considered entirely the responsibility of the author who can be held accountable at the same time next year.

Published by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism with the support of the Google News Initiative.

This report can be reproduced under the Creative Commons licence CC BY. For more information please go to this link.