Pedestrians walk past a BBC logo at Broadcasting House. REUTERS/Henry Nicholls

Pedestrians walk past a BBC logo at Broadcasting House. REUTERS/Henry Nicholls

Over the past two years, the relationship between news organisations and the public contributors who share their stories has been tested by a global, universally shared traumatic experience: the coronavirus pandemic.

I worked as part of a team of BBC News journalists gathering real-life stories from those who had lost a loved one to COVID-19, and those who experienced the impact of serious illness. As I listened to the vast spectrum of responses to deeply personal loss, I began to think about the importance of formalising journalistic practice of dealing with public contributors. Especially those dealing with trauma.

I use the term “public contributor” to refer to a specific group of news subjects. They are not public figures. They may be sharing experiences ranging from upbeat inspirational stories to brutally traumatic involvement in a globally reported disaster.

People in a public-facing or professional role can reasonably claim to be contributors to the news, but they are a discrete category as they will normally be speaking in a capacity related to that role. They are also more likely to have had prior experience or received media training prior to their engagement with us.

By contrast, we can expect most public contributors to be largely unprepared for both the processes and emotions of being part of the news cycle.

The standards I propose here were devised while thinking about those experiencing traumatic loss. By designing a code of conduct and guide that works for the most vulnerable, I believe we can create a standard that works for all public contributors. We owe it to those who lend us their voices and stories to ensure that the process of sharing them with our audiences does not, in the end, make things worse.

There are several organisations dedicated to helping journalists do a better job telling the stories of those who have been traumatised, and a lot of literature on the subject. Consider Disaster Action’s Personal Reflections and Guidance for Interviewers, the Dart Center’s training, or this recent report by the Survivors Against Terror group to start with.

Yet, when I gave a questionnaire to my colleagues at the BBC, 89% said they had interviewed someone experiencing traumatic loss for a story but fewer than 20% had read the BBC Academy’s “Tips for Working with Bereaved Families” or watched the Dart Center’s “Getting It Right: Ethical Reporting on People Affected By Trauma”.

With this in mind, I have proposed a very brief list of 11 key tenets that can act as a contract between journalists and contributors. In the full paper below, I outline my case for the BBC to consider adopting this as an official and publicly available Public Contributor Code. But I hope many public service and private news broadcasters will consider adopting them, too.

1. Always clearly give your name and outlet’s name when introducing yourself to a potential public contributor. They should be able to identify who they have had contact with or been interviewed by, as both a matter of courtesy and transparency.

2. Remember this is their story to tell. Support contributors by telling their story in a way that reflects what they feel is important. Repeat back what they have told you and ask if they have said everything they mean to say.

3. Informed consent matters. It should be freely given, actively stated, clearly documented and evolve throughout your interaction with a public contributor. We should never purposely publish private material or information that a public contributor has not consented to make public.

4. Ensure that you have undertaken training to interview contributors dealing with difficult or distressing subjects. Dart Center’s ethical reporting training is freely available here. Act in a way that is sensitive to the contributor’s needs and aims to add no additional trauma to their life.

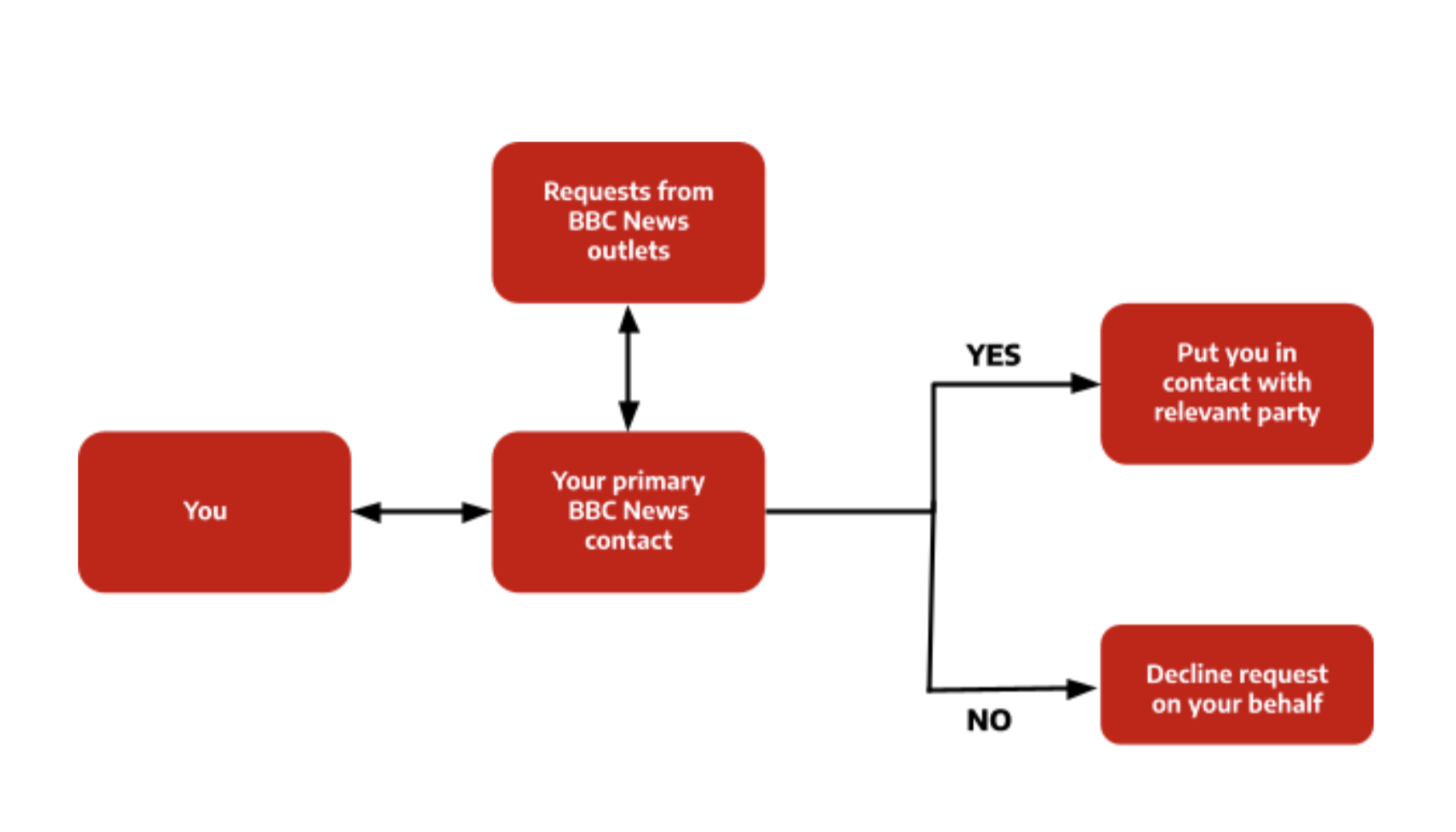

5. It’s confusing to be contacted by multiple reporters, especially when they’re all from the same outlet. Set up a shared document with colleagues and departments and agree a primary news contact for each person. As Ruth Palmer puts it: contributors may not trust journalists in general, but they will make an exception for the journalists who have taken the time to listen to them.

6. Recognise that being involved in the news is an unusual experience. Explain the news-making processes to your contributor to help them make an informed decision about what level of participation they are comfortable with. This includes fully explaining any interview recording processes, introducing all personnel present, and giving advice on where a contribution might appear and who else may have access to it.

7. Always be guided by respect for a contributor’s space and needs, in particular when pre-recording. Ask for their preference as where and when they would feel most comfortable speaking with you. Never pressure them into a location or time they are not comfortable with. Offer to take off your shoes when entering their home, and don’t move furniture without permission.

8. Tell them the time and date they can expect to see the story published or broadcast, and let them know if that changes.

9. In the case of a major news story, offer to share your story with other outlets under a pool agreement to prevent them being pressured to give multiple interviews about something which may be difficult and traumatic to discuss.

10. Give the contributor advice about the potential impacts of being in the news following publication. This includes:

11. When you make a mistake, apologise and work with the contributor to correct it as quickly and fully as possible.

If we expect audiences to trust in the stories they engage with, then we must make sure they can trust our processes for gathering and telling them. Journalists often demand transparency from public figures, but audiences also have a right to expect it from us.