Passengers wait for Light Rail Transit train at a station in Kuala Lumpur. REUTERS/Lim Huey Teng

Passengers wait for Light Rail Transit train at a station in Kuala Lumpur. REUTERS/Lim Huey Teng

Based on interviews with a strategic sample of 11 publishers in eight low- and middle-income countries, in this report we analyse how various digital publishers across a range of Global South countries approach digital platforms: both big platform companies such as Google and Meta; rapidly growing ones, including TikTok; and smaller ones such as Twitter and Telegram.

We highlight key shared aspects of their approaches that can serve as inspiration for journalists and news media elsewhere, in terms of how they see platforms (what we call ‘platform realism’), how they approach them in their day-to-day work (what we call ‘platform bricolage’), and key aspects of their overall approach (what we call ‘platform pragmatism’).

First, we show that our interviewees generally see platform companies through the lens of platform realism, based on five shared tenets, with platforms generally seen as:

In terms of how they use platform companies for their own purposes, each of the publishers we interviewed has its own editorial mission and funding model and operates in a different context. These missions and models, as well as their contexts, inform different choices about how they engage with platform opportunities and manage the accompanying platform risks.

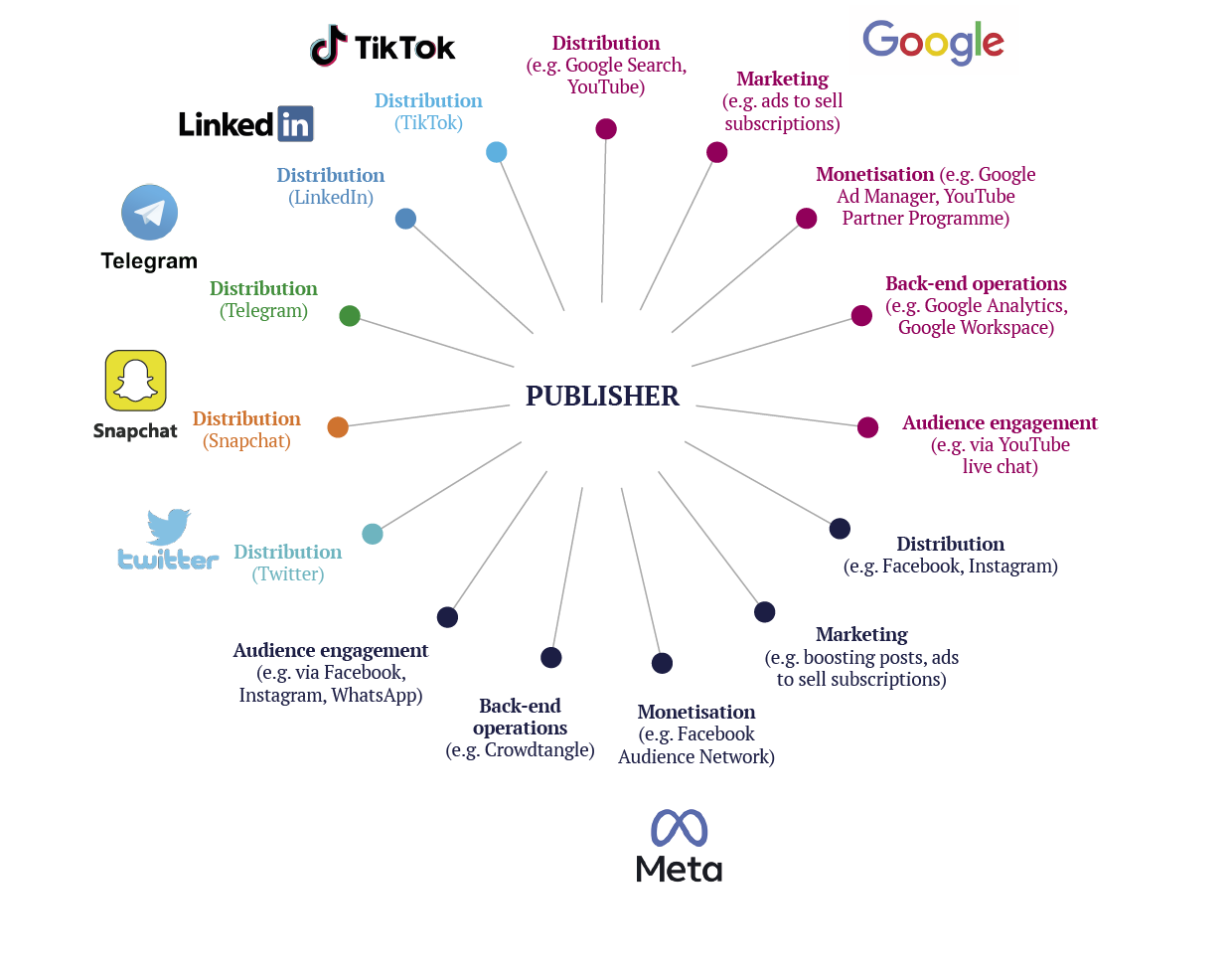

Beyond frequent use of search engines, social media, and other platforms in reporting, the main ways the digital publishers we interviewed use platforms include (a) distribution, (b) marketing, (c) monetisation, (d) back-end operations including analytics, and (e) audience engagement and community building.

It’s important to note here both the commonalities – all our interviewees used several platforms for several different purposes, and everyone engaged in at least some way with various parts of Google and Meta, even if sometimes reluctantly and in frustrating ways – and the differences.

We summarise the interviewees’ different approaches as platform bricolage, where digital publishers with necessarily limited resources – both in terms of money and access to developers – pick and choose which platform products and services it is worth integrating into the stack of other tools and technologies, whether off-the-shelf or bespoke, that they rely on to do their job. At the same time they remain keenly aware that platform products and services are tied to the strategic and commercial interests of the companies that provide them and are liable to change with little or no notice.

Platforms compete with publishers for attention, for advertising, and for consumer spending, and are often used in a wide range of ways both orthogonal and sometimes antithetical to the interests of journalists and news media (whether by individual creators or by political actors attacking independent reporters). But publishers can also use platforms for their own purposes.

The overall approaches the publishers in our strategic sample take to platforms have some commonalities that cut across different editorial priorities, funding models, and tactical choices in terms of which platforms are used for what – these commonalities can be summarised as platform pragmatism based on five broadly shared components:

We hope these findings of how a strategic sample of digital publishers from the Global South with a demonstrable track record of success approach platform companies will be useful as an inspiration for publishers elsewhere.

How do digital publishers in the Global South deal with various platforms and what have they learned along the way? In this report, we examine the different strategies and tactics pursued by a range of digital-born news media operating in low- and middle-income countries with an often mixed record on media freedom. They publish in digital media environments that are characterised by deep-seated inequality in terms of access and mobile-first; where platforms play a dominant role in terms of how most people access and find news; and where some politicians and other powerful actors often use platforms to attack and harass independent reporters.

Based on interviews with 11 publishers in eight countries, we examine commonalities and differences in how they approach various platforms – both big platform companies such as Google and Meta; rapidly growing ones, including TikTok; and smaller ones such as Twitter and Telegram – and the insights they have arrived at along the way, because we believe journalists and news media elsewhere can learn from their experience.

We find that most of our interviewees see platform companies through the lens of a set of shared tenets we describe as ‘platform realism’. They selectively engage with them in different ways, depending on their specific editorial priorities and funding model, on the basis of a pick-and-mix model we call ‘platform bricolage’ (using the lexical sense of construction or creation from a diverse range of available things). Across the differences in how they work, their approach has a number of commonalities we summarise as ‘platform pragmatism’.

Our findings capture how digital-born publishers reject the hype that sometimes surrounds the opportunities platforms offer, are keenly aware of the risks and contingency that comes with relying on them, and are focused on identifying the benefits that they – given their varied specific editorial ambitions and fundings models – can realise by engaging with platforms.

Their approaches are not necessarily always categorically different from those taken by legacy publishers, or publishers in more privileged parts of the Global North. But because they operate without legacy channels to reach audiences, legacy revenues to sustain their operations, or legacy brands that help maintain some direct connection with existing audiences driven by habit and loyalty, and because they operate in environments where platforms play a larger role, they have had to confront the role of platforms, and the questions of how publishers can approach them, more directly than many of their counterparts elsewhere in the world. This also means that publishers elsewhere can draw inspiration from their work, as they too increasingly have to come to terms with digital, mobile, platform-dominated media environments, and all too frequently with the kinds of political attacks and online harassment many of our interviewees have faced for a long time.

In the first section we outline the research the report is based on, and in the second section we explore how our interviewees see the different platforms they work with. In the third section we examine how they use different platforms for different purposes, and in the final, concluding section we present the lessons they say they have learned along the way.

Our strategic sample of 11 publishers across eight countries ranges from established digital news media with decades of experience, a demonstrated track record of success, and three-figure headcounts to newer entrants with half a dozen journalists.

Their overall editorial missions vary, but in every case they include some version of original factual reporting and/or explanatory journalism, rather than being more commentary- or opinion-focused, lifestyle- and entertainment-oriented, or primarily based on aggregation and derivative content. Their funding models vary from case to case and include both sites reliant on advertising – several with a significant focus on reader revenue (whether membership or subscription) – and elements of sponsored content, the sale of services (including fact-checking services for platforms but also, for example, marketing services), and in some cases grants and other non-profit sources.

They are all digital natives and thus, as the Daily Maverick publisher and CEO, Styli Charalambous, told us for a previous piece of research (Nielsen et al. 2020), ‘born in the fire’. As he explained to us in 2020,

In contrast to long-established and often larger legacy publishers, the Daily Maverick, Charalambous continued, has ‘been in an existential crisis for the better part of a decade. That has been our norm’. ‘You kind of get used to operating like that,’ he explained. ‘That’s just our reality, and we’ve accepted that, and we work with that [and] within those limitations we still force ourselves to try and grow. And we’ve grown our newsroom every year.’ Hard-scrabbling, principled entrepreneurs, succeeding against the odds in a challenging environment – many publishers could be described thus, but these more than most.

Digital publishers, perhaps even more than legacy publishers, take a wide range of forms, and it is hard to generalise across a constantly evolving, heterogeneous, and largely unmapped population (though see important work by Agarwal 2022a; Robinson et al. 2015; Schiffrin 2019; Sembra Media 2021) or determine what a representative sample would look like.1 We have therefore opted for a strategic sample of publishers that captures both a degree of commonality of purpose in their commitment to journalism and a degree of variation in terms of how they pursue and sustain their work. The organisations covered are listed in Table 1.

Table 1: Publishers included in the sample

Because our conversations covered sensitive strategic issues and sometimes fraught relations with powerful platform companies, we have anonymised all our interviewees. It is important to stress that this is a small, strategic sample of organisations willing to talk about often challenging issues, and that their experiences will sometimes vary from other digital-born publishers. However, we believe their approaches and lessons learned are important and can inform decision-making by other publishers, whether digital-born or legacy.

The countries our interviewees operate in vary greatly in terms of income, market size, and political pressures on independent news media. They are all part of what is sometimes referred to as the Global South, an exceptionally broad and heterogeneous category. As middle- and low-income markets with a mixed record on media freedom, we believe the countries our interviewees operate in are more representative of the global situation facing journalists and news media than the unusually privileged markets in North America and Western Europe.

To be able to provide some context beyond income classification from the World Bank and media freedom assessments from Reporters without Borders, we have deliberately focused on countries that are included in the Reuters Institute Digital News Report, and we include key data points on each country in Table 2 to provide a sense of the different markets our interviewees operate in.

The way our interviewees describe platforms can be summarised as platform realism. It is based on five largely shared tenets. Platforms are generally seen as

First, platform companies collectively are seen as integral and inescapable parts of the digital media environment, primarily because of their popularity with users. While the publishers we spoke to are often quite selective about which particular platforms they engage with, how they use them, and how much they invest in each, overall, they clearly recognise that the vast majority of internet users rely heavily on a range of different platforms for almost every conceivable purpose online, including accessing news. This represents opportunities. We ‘began as a Facebook page’, one Indian publisher says. We were ‘born on Twitter’, a Latin American publisher explains. This reliance on platforms by users provides practical reasons for engaging with platforms, as this is where the people publishers want to reach are found. One of our interviewees from Africa says ‘publishers used to own [audience] reach, right? But no longer.’ ‘We understand that people exist in the world of social media’, another publisher from Latin America says. ‘There was a time when maybe news publishers could have developed their own take on distribution, but that time we missed that slot, we have to rely on these big players,’ an Indian publisher explains.

For some, the activity of the publishers’ target demographic also provides principled reasons for engaging with platforms. As one interviewee explained, ‘Our objective and the reason [we] exist is because we want to inform people and we want to create rigorous conversations about politics and about democracy. And the people are not in our website, they are on the platforms.’

Second, platform companies are seen for what they are: self-interested, powerful for-profit actors with global operations, in most cases headquartered in the United States and thus far removed from where our interviewees operate. They are seen as primarily oriented towards their biggest markets, their biggest partners, and the places where they face the greatest political pressures. As one African digital publisher says, ‘unless you’re [a] certain size, you don’t really get as much support and wisdom from these platforms. … They care about publishers that will contribute to their bottom line.’ Another makes a point about the various headline-grabbing news- and journalism-related initiatives from Google and Meta: ‘There’s a reason it went through Europe twice and the Americas, and everywhere else, and only then came to Africa, right?’ None of our interviewees expected charity from platforms, or believed they had much leverage with them, or thought of them as public utilities. Instead, they approached them tactically, seeking out opportunities where and when an individual publisher’s interests seemed largely aligned with a given platform’s, recognising that in other areas their interest might well be different, or even in direct opposition. ‘They get something out of it, and we get something out of it’, one Indian publisher says.

Third, interviewees explicitly cast even long-established incumbent platforms as amorphous, ever-changing, and opaque in their operations. While they described some differences in how clearly they felt different platform companies communicated about ongoing or upcoming changes (ranging from poorly to not at all), and how dependable they were, in their experience, as indirect or direct partners, no one expected any one platform to operate in a predictable, stable way. Most explicitly recognised that many platforms are continuously and aggressively competing with one another, in part through constant adaptation, experimentation, and imitation. Most have stories to tell about the impact. ‘We [once] lost half of our visits [due to] changes at Google Search’ one interviewee says. ‘The second last major change to Google algorithm … really helped us’, an Indian publisher says, ‘but that has also changed’. ‘They’re always changing, and you always have to be like doing what they want’, one Latin American publisher explains. Just as our interviewees were generally deliberately and proudly tactical in how they approached platforms, constantly evaluating what served their ideals and interests best, they always kept in mind that platforms would be doing the same.

Fourth, none of our interviewees had any illusions about the relative importance of news to any one platform, even those who have long integrated news as part of the wide range of different things they help users find or offer up in feeds. One African publisher says ‘We’re a rounding error in the world of the platforms. We’re insignificant and we [are] made to feel insignificant as well’. ‘Platforms are increasingly looking at prioritising influencers and personalities over news publishers’, an Indian interviewee says. ‘So for the platform these guys are more important’. (In recent years, first TikTok and later Snapchat, Instagram, and YouTube have all – without facing political pressure to do so – launched ‘creator funds’ to pay a small subset of individual creators.) In an exceptionally competitive content economy – where news publishers compete for attention and visibility not just with one another, but also with a wide range of other creators, strategic communicators coming out of the corporate world, politics, and civil society, as well as with a multitude of individual users’ expressions – news as a whole, and especially any one news publisher, was seen as of limited importance to platforms, whether big or small. News publishers also clearly recognise that some platforms (e.g. WhatsApp) seem to actively want to avoid serving publishers, offer few, if any, bespoke tools for them (e.g. TikTok), or have systematically been working to reduce the role of news (e.g. Facebook) – even as others (e.g. Google, both in terms of search and as a provider of advertising solutions) continue to engage with publishers.

Fifth, most of our interviewees highlighted platforms’ relative lack of interest in smaller and/or poorer markets far from the corporate headquarters. For all the talk of global markets and ‘the next billion’, as one Asian publisher explains, ‘when it comes to technology, a lot of things are just not available [here]. … Maybe we are the afterthought [laughs] in the APAC region.’ In most cases, their relations with platforms are primarily through online self-service systems. A few platforms, primarily Google and Meta, have country representatives and sometimes dedicated news partnership teams but, as one African publisher says, ‘Let’s put it this way, I employ more people in this country than Google and Facebook combined.’ Even when such local staff is in place, they are seen as relatively powerless and not necessarily particularly knowledgeable, and therefore are considered basically irrelevant by many of our interviewees. Potentially important product changes are often communicated globally and publicly before it reaches local staff. One Indian interviewee explains, ‘The information about the new update would reach us way before a partner manager informs us.’ Whether the issues digital publishers face are relatively mundane technical problems or more dramatic, such as news coverage of police violence being taken down as ‘explicit content’ or large-scale coordinated harassment, sometimes by political actors (see Sircar 2021), or state attempts at influencing content moderation (see, e.g. Agarwal 2022b), in our interviewees’ experience, the expertise and/or authority required to address the issue is rarely found locally. Sometimes it is in platforms’ regional offices, and often only all the way back in corporate headquarters that sometimes seem to have little time for quarrels in faraway countries between people of whom they know nothing.

Thus, interviewees’ platform realism highlights aspects of the role of platforms also identified by academic researchers – that they are central to much of the digital media environment, that they are self-interested actors, that they are constantly changing and, in many cases, not that interested in news, and they are rarely as committed to poor countries as to more lucrative markets (Barrett and Kreiss 2019; Nechushtai 2017; Nielsen and Ganter 2022; Poell et al. 2022a; Poell et al. 2022b; Punathambekar and Mohan 2019; Rashidian et al. 2019). Legacy publishers will also hold many of the tenets identified here, but because they are more exposed to competition from platforms (as audiences and advertisers move from print and broadcast to digital platforms) the competitive dimension of the relationship between platforms and publishers is often more salient for them, and the possibilities for complementarity less so (as they tend to be outweighed by the importance of protecting existing operations and shoring up direct reach via websites, apps, etc.).

From our interviewees’ perspective, relations between publishers and platforms are often purely transactional, sometimes complemented with joint interests or even ideals, but even in the latter cases, as one publisher explains, ‘there’s always going to be this friction … between us and them’. A phrase used by several interviewees was ‘every time, there is a catch’. Transactional interactions can be purely commercial – as illustrated by the quote above about what contributes to the bottom line, and by any number of the ways detailed below in which publishers use platforms in ways that benefit both – or they can be more about optics. One African publisher who has received an innovation grant from the Google News Initiative says, ‘It did really well for us, and it is [also] one of the projects they keep highlighting in case studies, so it’s worked well for them.’

This leaves digital publishers in a position where they clearly see platforms as offering a range of opportunities, but also accompanying risks, and with a clear recognition that even successful, relatively big, digital publishers are tiny compared even to smaller platforms such as Twitter (let alone larger ones). When engaging with them, the relationship is profoundly asymmetrical. As one African publisher explains in a passage worth quoting at length:

We are, an Indian interviewee explains, ‘[figuring] out ways to do content that … fits in with our sort of ethos, and also there’s a very tiny overlap in that Venn diagram [of] what we believe in and then what works for Twitter and Facebook. So we’re just trying to find that kind of a balance.’

Beyond frequent use of search engines, social media, and other platforms in reporting, the main ways the digital publishers we interviewed use platforms include: (a) distribution, (b) marketing, (c) monetisation, (d) back-end operations including analytics, and (e) audience engagement and community building. It’s important to note here both the commonalities – all our interviewees used several platforms for several different purposes, and everyone engaged in at least some ways with various parts of Google and Meta, even if sometimes reluctantly and in frustrating ways – and the differences.

Each of the publishers we spoke to has its own editorial mission and funding model and operates in a different context. These missions and models, as well as their contexts, inform different choices about how they engage with platform opportunities and manage the accompanying platform risks. With necessarily limited resources, both in terms of money and access to developers, they engage in platform bricolage as they pick and choose which platform products and services it is worth integrating into the stack of other tools and technologies, whether off-the-shelf or bespoke, that they rely on to do their job, even as they know that the companies who provide these tools are self-interested, powerful for-profit actors, prone to changing at little or no notice.

Distribution

Distribution is by far the most important reason publishers use platforms. But which platforms are most important, and how they are used, differs significantly based on strategic choices informed by a publisher’s editorial mission and funding model. The digital publishers we interviewed seek different balances between, at one end of the spectrum, some who have a strong on-site focus, generally emphasising website and email newsletters and relying on reader revenues and, at the other end of the spectrum, those with an off-site focus, with investment in platform-native and often bespoke content and revenues generated from advertising, sponsored content, or other sources reliant on reach (See Figure 1). Over time these different strategies contribute to different outcomes and, in turn, continuously inform tactical decisions about which platforms to focus on and why.

At one end of the spectrum, an African publisher says social media posts are purely a means to an end: ‘the end point is can we get people onto our newsletter and subscribe’. Content is distributed via social media, but the primary purpose is to serve as the top of a conversion funnel, raising awareness of the brand and potentially drawing in interested readers. Several of the publishers we interviewed have a similar focus. At the other end of the spectrum, a Latin American publisher – well aware of the travails of Global North digital media like BuzzFeed – says most of their distribution is on platforms, explaining that, for both principled reasons (the desire to be where conversations are happening) and practical ones (high reach helps sell sponsored content), ‘we decided to prioritise not only our website but the content we developed specially for social media platforms. So we have formats specially made for each [priority] social media platform.’ Again, several other publishers we interviewed invest significant effort in native content for a selection of specific priority platforms, sometimes running several verticals with a different focus in addition to news (e.g. health, fact-checking, lifestyle).

In terms of the relative importance of different platforms, it depends in part on the type of platform and in part on what each publisher is trying to achieve.

In terms of search, given its dominant position, it is unsurprising that Google Search is repeatedly mentioned as, as one African publisher puts it, ‘our main source of visits’.2 This is in line with top-line data from market intelligence company Parse.ly, which suggests that on aggregate, among their clients, Google Search is the single largest source of external referrals.3

In terms of social media, every publisher in our sample invests some effort into Facebook, but, in line with the parent company Meta’s decision to reduce the overall role of news on the platform over the years, even for off-site publishers it is not what it once was. As one Latin American publisher with a large following and a focus on reaching people on social platforms says, ‘Facebook is also important but I will say it’s not that important.’ For publishers with an on-site focus, it is generally even less important. ‘We’ve hardly ever done really well on Facebook’ one says. Another explains ‘it’s not really good at bringing people to our own platforms, which we need. They’re good at keeping them’. One African publisher says ‘something like eight per cent’ of their site traffic comes from Facebook, in line with Parse.ly

aggregate averages. While publishers focused on off-site reach continue to invest in their Facebook presence, several on-site-focused publishers say they have automated their posting to the platform.

Two other established social media platforms come up frequently: the widely used Instagram and the smaller Twitter.

Interestingly, despite Instagram’s limited focus on news and news publishers, and the limited amount of traditional referral traffic the platform accounts for (in part by design), both off-site and on-site publishers frequently highlight it as a priority. ‘On Instagram [we] have a big community,’ one Latin American off-site-focused publisher says and adds, ‘we developed a strategy to reach young people and to inform them about politics with easy but rigorous content, so that’s another platform that we care about.’ Another off-site-focused publisher says Instagram is ‘the place that we have the broader contact with our audience’, and similarly invests in native content for the platform. While not all on-site publishers are investing in Instagram, one subscription-based African publisher says it is ‘very useful for us, and it’s actually changed a lot of the way that we do our work in the sense that a lot of ours is visual’ (though another with a similar funding model says they are currently deprioritising the platform due to the difficulty of converting reach to subscribers and more widely the difficulties of assessing the return on investment).

Twitter is mentioned by almost every interviewee but is used very differently from Facebook and Instagram. Though one digital publisher, pointing to limited referrals and little conversion says ‘we don’t really do Twitter’, most interviewees, irrespective of their strategic focus and funding model, invest effort in the platform, which one says has ‘outsized importance relative to its referral traffic’. One reason is that it is seen as an elite platform. ‘It is the platform where all the politicians and powerful people are and our coverage is focused on political and economic power. So if we create a conversation on that platform, it’s a really big impact for us,’ one Latin American publisher says. Another reason is that a significant number of news lovers also use it, including as an interface to some of their regular news sources, which is particularly important for many subscription-based publishers. As one on-site-focused publisher says, ‘Some of our most engaged users who visit a lot actually visit us through Twitter.’ Some interviewees express private reservations about continued investment in Twitter – ‘to be honest I don’t see much worth [but] I understand the perception thing is really important’, one says – but despite limited measurable returns on investment (and in many cases problems with online harassment) the platform continues to attract publishers.

The overall patterns in the use of search, and the long-established social platforms Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, are clear and consistent. There is greater variation when it comes to other platforms.

Several, but not all, of the off-site-focused publishers prioritise YouTube, mentioning it as among the primary platforms for distribution (and in a few cases, also for monetisation – more on this below). But for most of those who use YouTube, the higher costs associated with creating quality video, stiff competition for attention from both a multitude of individual creators and larger legacy media with more resources, and perception that the platform is not really widely seen by users as a platform for news, means that the site is often used in a less intense way – perhaps as an embedded video player on site and as a de facto archive of video content.

TikTok is still mostly an experiment for our interviewees – given limited resources, uncertainty about what on-mission content might work on the platform, and concerns over return on investment, at this stage those who are using the platform are, as one says, ‘dabbling’. A few interviewees mention LinkedIn but no one sees it as a major focus. Only one of the publishers we interviewed invests in Snapchat.

Finally, messaging applications rarely came up in our interviews. A few publishers are investing in Telegram, either as a channel for off-site reach or with a bespoke newsletter for members, and several have experimented with WhatsApp before. In one case, ‘we were basically kicked off because of course they don’t necessarily want publishers to be broadcasting on those platforms’. Some of our interviewees mention that other publishers still seem to be experimenting with WhatsApp, including for the distribution of PDFs and/or audio files.

When asked for examples of platforms they have abandoned, the only examples of a clean break that came up are Reddit, which one publisher has experimented with, and WhatsApp, which several publishers say they had to abandon as broadcasting functionality was reduced. But several more have reduced their investment in Facebook and Twitter by automating posting, using Echobox or similar tools, to maintain their presence on the platform without committing scarce editorial (human) resource to it.

Marketing

Marketing is an important part of how many of the digital publishers based on reader revenues use platforms. This goes beyond the distribution of content to paid promotion, especially on Facebook and in some cases other social media platforms. When relying on platforms for distribution, publishers are generally complementers, leaning into the opportunities that platforms provide for so-called ‘organic’ reach, effectively offering access to content in return for access to audiences (Nielsen and Ganter 2022). When publishers rely on platforms for marketing, they are customers, buying a service and paying in cash. ‘I run a lot of campaigns on these platforms,’ one interviewee says, describing this as key to the acquisition of subscribers. Another digital publisher, who invests minimal effort in Facebook for distribution – and more broadly takes a pretty dim view of the platform – goes on to highlight its utility as a marketing channel: ‘Facebook is where we still spend money on newsletter acquisition. We find Facebook has the lowest cost per lead on newsletters, [so] we are doing it as efficiently and as targeted as possible … and we’re happy with the cost per lead there.’

Some digital publishers express reservations about investing in marketing via platforms. One interviewee says,

The main paid promotions this publisher highlights as competing for their target audience of potential subscribers are, interestingly, foreign English-language upmarket titles trying to grow their international readership, mentioning for example the New York Times: ‘Because they advertise better on these platforms; they have more money to go round and put [on] ads while we don’t.’ Others highlight how larger legacy media in their market invest in paid promotion on social as ‘a cheap source of traffic’ that can, in turn, generate advertising revenues to cover the cost and deliver a return. Several interviewees say that some domestic legacy publishers able to sell advertising direct (rather than rely on programmatic ad exchanges) are aggressively investing in paid promotion on social media platforms to arbitrage between the rates they sell ad impressions at and the cost of securing these impressions via platforms.

Those interviewees who have tried investing generally say they see results. One says,

But spending still carries both long-term concerns about becoming reliant on paid distribution and more immediate short-term concerns about determining the return on investment. An African digital publisher says

Some advertising-based digital publishers do the same thing that other interviewees complain about legacy publishers doing, and still feel they can just about make this work at the margin when investing in paid marketing: ‘we drive ad revenue, we can basically arbitrage ad revenue by getting these people in’. But subscription- and membership-based digital publishers see clearer results because of their higher average revenues per user.

Monetisation

Many of our interviewees use platforms for monetisation, but the ways in which they do it vary in important ways.

For those reliant on advertising revenues, programmatic advertising sales primarily through Google’s services is important.4 Many struggle to sell advertising directly, either due to their limited scale and often less well-known brand (compared to larger legacy publishers), or in some cases at least in part due to political pressures on potential advertisers. One Indian interviewee explains that their direct sales to domestic advertisers are limited because ‘if a brand associated with someone who holds the government accountable or if a brand has an ambassador who says something that is not of the liking of the ruling party, there’s a lot of outrage’, and the site therefore relies more on direct sales to high-end international brands and on programmatic sales. One digital publisher who generates about half their revenue from advertising says, ‘For advertising, we are almost 100 per cent relying [on] Google Ad Manager and Google Ad Exchange as our primary advertising network.’ For ‘things like advertising, you can’t really escape from using Google’s platform’ another explains. This dominant position shines through in how direct relations with digital publishers in the Global South are handled. Another publisher also selling ads through Google’s Ad Exchange – who, in parallel, describe relations with partnership teams on the Google News Initiative as ‘meaningful dialogue’ – describes the relationship with Google’s ad tech business as

Beyond programmatic advertising integrated into written journalism hosted on a publishers’ own site, email newsletters, etc., while most of our interviewees have had no success directly monetising off-site content on platforms and are generally dismissive of platforms’ offers to work together to do so, a few of our interviewees have a different experience. These are generally larger digital-born publishers with focus on off-site reach.

One outlier relies in part on Facebook for off-site monetisation. In a marked contrast to many others, our interviewee describes Facebook as

Another explains that, of all the social media platforms that the publisher invests in – including Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, and Twitter – Facebook ‘is the only platform we are earning something out of’. One interviewee describes a similar use of YouTube, saying

Another says, ‘YouTube is an avenue where there is an opportunity to earn – a much bigger opportunity than there is on [other] platforms.’

Beyond direct monetisation through revenue-sharing arrangements on YouTube and Facebook, a few interviewees also mention that platforms play an important part in their work with sponsored content, where campaigns often require an investment in marketing to reach the traffic goals agreed with the clients paying for the content.

Finally, a few of the digital publishers we cover here make money from selling fact-checking services to platforms. One Latin American publisher says

Others have similar contracts, but only with a single platform, most often Facebook. Those engaged in this underline their desire to not become reliant on a single customer to fund their fact-checking work, but also describe the emerging market for fact-checking services as opaque and highly variable. One describes a competing platform’s approach thus:

Back-end operations

Digital publishers describe a range of uses of platforms that are back-end and generally not visible to their users. This is very different from active and public use of, for example, social media for distribution, paid platform campaigns for marketing, or programmatic advertising to generate revenue, but it is important to highlight.5

The single most widely mentioned use is Google Analytics, which many of our interviewees describe as one of the tools they use to understand their audience and track performance. One interviewee explains:

Another says

Several also mention using Crowdtangle, a tool provided by Meta, to analyse their own and competitors’ performance on social media.

In terms of individual social media platforms, interviewees are keenly aware of how reliant they are on data from the (self-interested) companies behind the platforms in question. One says,

Another highlights the underlying concern that many flag: ‘Can anyone trust Facebook Insights? That’s also a question.’

Beyond this, digital publishers are generally using the built-in analytics that individual social media platforms offer, as well as the tools they provide for those wishing to produce native content, such as Facebook Creator Studio and its counterparts. Our interviewees also describe other back-end uses.

YouTube, for example, is used even by publishers who do not see it as a priority distribution channel in general, both as their on-site video player and archive, and sometimes for specific purposes such as podcast distribution. One publisher who does not invest in YouTube for daily output or general reach says

Another use is reliance on platform products for business communications, as an alternative to other enterprise solutions. Here, as with marketing, digital publishers are customers of platforms, paying for services rendered. One interviewee says, ‘We’ve been using the Gmail applications for free for the past five, eight years because we were considered non-profit’. But, illustrating the fact that there often is a catch, the interviewee continues:

This is aligned with the broader consciousness that platforms are self-interested and ever-changing, including when it comes to the terms of use of tools that publishers – like each of us as individual end users – can come to be highly dependent on. As one interviewee says about back-end solutions offered by platforms:

Audience engagement and community building

Finally, some of our interviewees say they use platforms for more in-depth, active audience engagement and community building, going beyond distribution on the ‘we publish, you read’ model. One Latin American publisher says, ‘We focus on having a community. On Instagram, I think that we have a solid community of followers.’ Another says,

Digital publishers with an on-site strategy based in large part on reader revenues in particular are increasingly thinking about platforms as a tool for deep engagement rather than wide reach. Sometimes this has an open, public component, as in the case of one interviewee who describes the main rationale for investing in Twitter as being that ‘a lot of contributors do come through there’. In other cases, the aim is to develop something more exclusive, such as with the private use of messaging apps: ‘We want to create a dedicated Telegram newsletter’ for supporters, one publisher explains.

This kind of positive and interactive ongoing engagement with a community represents one of the abstract ideals social media were originally associated with, and which generated some excitement. But at least as important as examples of such use from some of our interviewees is that most make no attempt to use social media for such purposes, either embracing a classic ‘we publish, you read’ approach to their journalism, or focusing their audience engagement and community-building efforts on more private spaces, including emails and offline events. This is in part because many social media are seen as poor places – or even hostile environments – for genuine engagement. Several of our interviewees describe how they and individual members of their newsroom, in particular women and reporters from minority backgrounds, often face online harassment on social media (especially on Twitter), in some cases in what seems to be campaigns coordinated by political actors and their supporters. None of our interviewees feel that platforms are particularly engaged in dealing with this issue. When it comes to online harassment, one explains:

In summary, different publishers with different editorial priorities, different funding models, and limited resources make different decisions about which platforms they engage with, and for what purposes, across distribution, marketing, monetisation, back-end operations, and audience engagement and community building. The resulting relations vary not just by publisher, but also by platform, with qualitatively and quantitively different relations with big platforms (Meta and especially Google) that are important parts of much of what most of our interviewees do –and often quite integral to their tech stack – as opposed to smaller platforms where the transactions are often simple and based on the basic ‘access to content in return for access to reach’ model that has long characterised relations between publishers and platforms (Nielsen and Ganter 2022) (See Figure 2). These relationships can be stylised as in Figure 2 (on next page), capturing both the range of uses and platforms many publishers engage with and the particular importance of two of the biggest, Google and Meta.

What our interviewees, and other digital publishers in the Global South, do is difficult. Many of them face direct political attacks and organised harassment both online and offline, skittish advertisers fearful of the repercussions of investing in independent news media that inconvenience the powers-that-be, and unforgiving competition for attention, advertising, and the money people are willing to spend.

Platforms – from the largest companies with multiple widely used products and services (Google and Meta) to less widely used established players (such as LinkedIn, Twitter, and Snapchat) to smaller ones such as Telegram and rapidly growing ones, especially TikTok – compete with publishers in many ways. But publishers can also use them for their own purposes.

The way in which our interviewees do that can be summarised as platform pragmatism, based on five broadly shared components:

The first component and starting point is – simple as it sounds in principle but difficult in practice – clarity about the editorial mission, funding model, and target audience. Without clarity of purpose it is hard to develop strategies and tactics for dealing with platforms, let alone assess whether one is achieving one’s goals. Developing and maintaining that clarity, communicating it internally, and maintaining it is a challenge.

The second component is adaptability. Every interviewee we spoke to stressed that the environment is constantly changing, including platforms, and that they expect no stability. Even the biggest, most successful platform incumbents are continually changing their products and services as they compete with other platforms in what former Google CEO Eric Schmidt once called the ‘platform wars’. User base and user behaviour changes, technology evolves, and platforms often scramble to imitate features from successful competitors and new rapidly growing entrants.

Clarity and adaptability provides the basis for the third component: selective and diverse investments of scarce resources in those platforms that a publisher believes might generate an editorial and/or commercial return on the time and money invested, and hedging against the platform risk that comes with being overly reliant on any one platform. In many cases, investment can be described as ‘two-plus’, with several of our interviewees highlighting two platforms as being particularly important for them.6

Investment in a limited number of key platforms is then accompanied by, first, carefully curtailed commitment of minimal resources to make at least something of other platforms (often through the automation of posting via Echobox or similar services), and second, minimal investment in experimenting with other possible opportunities, whether on long-established platforms such as LinkedIn or Telegram or newer entrants like TikTok. Off-site oriented publishers still have a website but it is often relatively less important. Beyond platforms, these publishers primarily invest in those channels that can provide the most direct connection with the audience, e.g. website and emails newsletters. This is especially true of those publishers committed to an on-site strategy and reader revenue as a significant part of their funding model.

‘Two-plus’ provides a way to focus efforts on the pursuit of platform opportunities while hedging against platform risk by avoiding complete lock-in and too heavy a reliance on any one platform, as well as the ability to ramp up investment in platforms one already has some familiarity with and presence on, if and when a priority platform ceases to deliver reasonable returns. It also means that none of the digital publishers we cover felt any need to be first movers when a new platform such as TikTok takes off, because the returns on editorial and commercial investment are simply too uncertain. An element of focus is important here, especially for smaller digital publishers, because resources are ultimately scarce and competition for attention intense – shovelware has never performed well online, and platforms are no exception.

The one platform company none of our interviewees really felt able to effectively hedge against is Google, especially when it comes to search. Given the market share of Google Search, virtually all search engine optimisation (SEO) efforts are directed at the dominant player. Changes to ranking algorithms can have dramatic effects and be keenly felt, as many of our interviewees get a large share of their traffic via search – traffic they want, and invest in attracting, but also traffic they know can fluctuate wildly as algorithms change from time to time. Not all the publishers we cover rely on advertising, but all those who do use Google’s programmatic advertising services and, again, feel they have few effective alternatives. Almost all use Google Analytics – some as their main analytics, others as one of several tools. YouTube looms large for many, and others are using Gmail or other back-end services. While generally described as better than with Meta, in practical terms, relations with Google are often mixed – many interviewees explicitly praise news partnership managers and staff on the Google News Initiative as friendly and helpful, while also highlighting that other parts of Google – search, advertising – are ultimately more important for them, and that understanding them is hard and frustrating work.

The fourth component is proactive relations, where, given that local country representatives from platform companies are often seen as of little use, and partnership representatives friendly and helpful but not all that important, several interviewees describe how they proactively seek to manage their relations with key people at key platforms, from systematically seeking regular meetings to efforts to maintain personally friendly relationships with individuals in these companies (including individuals working closer to corporate centres of power in California or regional headquarters) to help deal with problems and issues as they come up.

The fifth component is monitoring and evaluation, as data and analytics provide a key way to avoid being led by the dead hand of tradition, whatever happens to be fashionable, or whatever the platforms might be promoting. The monitoring is hard, especially when it comes to on-platform behaviour that generally can only, or mostly, be monitored with platform-provided data, but something many of our interviewees invest considerable time and effort into is using multiple tools (Google Analytics, Chartbeat, Crowdtangle) to try to avoid full reliance on only what a platform provides about itself. The evaluation too is hard, and not always easy to quantify. It is noteworthy here, for example, that two of the social media platforms most frequently highlighted in our interviews as a priority right now, Instagram and Twitter, are also explicitly recognised as platforms that provide very little in terms of referral traffic and no significant opportunities for off-site monetisation.

Clarity, adaptability, selective and diverse investments, proactive relations, and constant monitoring to assess whether investments in platform opportunities are delivering an editorial and financial return are the features of platform pragmatism that publishers use to justify the accompanying risk and the time and money spent. Every organisation is different; their strategies, funding models, and contexts vary, and their relationships with platforms also vary from company to company. But together these five components help guide how the different digital publishers we interviewed approach platforms. They expect nothing from them, know the risks involved, and seize the opportunities they see. From their point of view, as one publisher says, ‘platforms are not friends, and they are not enemies’, they are integral parts of the digital media environment, self-interested, powerful for-profit actors that represent opportunities and risks that our interviewees navigate on the basis of their own editorial ideals and organisational interests.

It is important to be clear that our strategic sample is small, and that digital-born publishers are a large and heterogeneous population – other publishers elsewhere will have different editorial focus and will have approached platforms differently. Many of them also face issues with platforms that go beyond those covered here, for example lack of access to efficient payment systems. Context also matters – the level of coordinated political attacks and harassment publishers face varies greatly, both from publisher to publisher and country to country, and the overall level of media freedom and risk of media capture differs, as does which platforms are most popular with the public. Beyond the shared features highlighted here, each points to a different key learning when asked directly what advice they would share with others.

Furthermore, the approaches identified here are not limited to digital-born publishers from the Global South. Digital-born publishers in the Global North will share some of the same features (as they too cannot rely on legacy channels, legacy revenues, or long-established brands, but are native to a media environment dominated by digital, mobile, and platform media). Legacy publishers who have put digital at the heart of their strategy will have some things in common with at least some of our interviewees, even though the ways in which they balance platform opportunities and platform risks will be different, given that some of them have a larger audience coming direct to them than most digital-born publishers, and some have a little more leverage with platforms generally than their smaller, digital-born counterparts (Poell et al. 2022b). The risk that some publishers, driven in part by a fear of missing out, would throw themselves at every platform opportunity with little clarity about how to assess returns on investment also seems to have receded somewhat in the industry more broadly, as more and more publishers, whether digital born or legacy, have clarified which platform opportunities are most important for them, and which platform risks they are willing to take on (Nielsen and Ganter 2018; Sehl et al. 2021; Nielsen and Ganter 2022; Ross Arguedas et al. 2022).

We focus on our strategic sample and their approaches here because we believe their demonstrated track record of success in the face of considerable challenges and significant precarity, including the vagaries of dealing with platform companies, is something many publishers elsewhere can draw inspiration from. They are not only ‘born in the fire’, as Daily Maverick publisher and CEO Styli Charalambous puts it. They have also made a lot of it.

1 See also Sen and Nielsen 2016.

2 No other search engines come up in our interviews.

3 Parsel.ly's Network Referrer Dashboard

4 Programmatic advertising is the process of automatically buying and selling digital advertising space.

5 This often also includes cloud hosting from companies such as Amazon or Google, but we do not cover that here.

6 Which platforms vary: several highlighted Instagram and Twitter, others YouTube and Facebook.

Rasmus Kleis Nielsen is the Director of the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism and Professor of Political Communication at the University of Oxford.

Federica Cherubini is the Head of Leadership Development at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

We are grateful to the research team at the RISJ for their feedback and input on this manuscript.

Published by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism with the support of the Knight Foundation.

This report can be reproduced under the Creative Commons licence CC BY. For more information please go to this link.

At every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s sources - all in 5 minutes.